When a company is backed into a corner with allegations of fraud and a plummeting stock price, it can either admit defeat, or fight to the bitter end. In June of last year, SkyPeople Fruit Juice chose the latter. Its stock rebounded by 20 percent, the hedge fund that called it out has a complex legal battle on its hands, and in the process everyone has learned a thing or two about how business is done in China.

SkyPeople says it is in the business of producing and selling fruit juice concentrates, fruit beverages, and other pulp products.

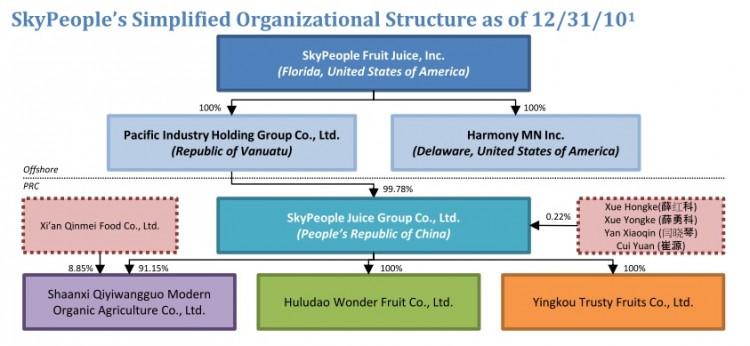

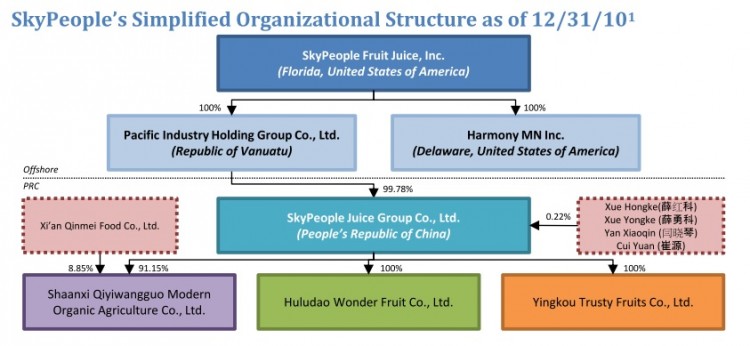

Its organizational structure is a little complicated. Sky People Fruit Juice Inc. is a holding company incorporated under Florida law. It has two direct wholly owned subsidiaries: Pacific Industry Holding Group Co. Ltd., a company incorporated in the Republic of Vanuatu, a small island near Australia; and Harmony MN Inc., registered in Delaware. Pacific Industry Holding Group owns the actual company tasked with making the juice and concentrate products: SkyPeople Juice Group Co. Ltd., which is organized under the laws of the People’s Republic of China; it has three subsidiaries.

SkyPeople’s financials indicate that it has done booming business for several years running, and at the current rate of growth would become one of the largest companies in its industry within a decade.

A report on the company by Kevin Barnes of Absaroka Capital Management, however, called all that into question. His report, titled “Pulp Fiction” published on June 1 last year, portrayed a stark picture: that visits to company facilities revealed idle factories, old equipment, and the smell of decaying pears; that the company did not (as it claimed) own the largest Kiwi fruit plantation in Asia, that its products can hardly be found on shelves, and that the fabulous margins, inventory turnover, accounts receivable, and other figures on its financials indicate “potential accounting shenanigans.”

Barnes asserted that the company was worth less than 10 percent of what it claimed to be in its financial documents filed with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

The response from SkyPeople was swift. On June 10, nine days after the publication of “Pulp Fiction,” Barnes got a sharp “demand letter” from high-powered lawyer Neal Marder. It came with an affidavit for Barnes to sign retracting the report and a copy of a lawsuit Marder threatened to file if Barnes did not retract.

If Barnes signed the affidavit, he would be saying that his report was false, which would damage his career. Instead he hired his own counsel, Arlene Fickler with Schnader Harrison Segal & Lewis in Philadelphia. On July 8 SkyPeople’s lawyers sued Barnes in the United States District Court of Wyoming. Barnes was accused of libel, and was being sued for damages. Marder was leveling the grave claim that Barnes had simply fabricated information.

The plot thickened in the course of the legal battle, after Barnes hired counsel in China. According to affidavits submitted to the court by Chinese lawyers, they found that SkyPeople’s 2009 income statement and balance sheet had been removed from its filings with the State Administration for Industry & Commerce (SAIC), a regulatory body with which all businesses in China are required to file their financial statements.

This did not particularly matter to Barnes’s legal case, because he had the files in his hand already—he'd used them in his original report—and besides that, other SAIC files of Sky People referred to the same figures which his claims of fraud had been based on.

Missing files that had been there only months ago were just one of the problems Barnes’s team encountered, however. Their investigators on the ground in China also started getting harassed.

According to court records, after Zhao Junwen, a lawyer whose services were contracted by Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld, went to search for the business files of SkyPeople and one of its Chinese subsidiaries, he was told they had been sent elsewhere for electronic scanning. After he left the government offices he got a call to his cell phone asking why he was investigating those companies. Seven days later he got another phone call. The man on the other end, who declined to identify himself, told Zhao to cease his investigation into the company “otherwise he would come down hard on me,” Zhao said in an affidavit submitted to the court.

According to Roddy Boyd, a financial journalist who first reported the case, investors began pulling their money out of Barnes’s fund because of the litigation. The lawyer retained by SkyPeople, Neal Marder, (who charges nearly $1,000 an hour, according to Boyd—to which Marder said “that’s not accurate” when he was reached by phone) had according to Boyd suggested to Barnes’s lawyers that the case could be dropped for $50 million. Marder did not confirm or deny that figure; he said it would be “totally inappropriate” to comment on settlement discussions.

Barnes will continue the battle. Absaroka Capital Management declined comment because of ongoing litigation. Barnes’s lawyer, Arlene Finkler, could not be reached.

Boyd writes that Marder’s firm, Winston & Strawn, has been making a killing from defending SkyPeople. The firm would not say how much it has made in fees. Its China-based lawyer on the case, Laura Luo, was a legal adviser to RINO International Corporation, which was delisted after allegations raised by short sellers that it was a massive fraud.

While all this goes on, SkyPeople Fruit Juice is contending with two other sets of charges. According to a Bloomberg article, the company reneged on promises to Chinese domestic investors to pay them handsome returns once it listed on Nasdaq. Further, a group of shareholders in the United States in November 2011 started a class action lawsuit against SkyPeople for violations of federal securities laws.

The investors will probably not have much chance of recovering their money. They bought shares in a holding company in Florida whose assets are a trust in the Republic of Vanuatu and a firm in Delaware. The company’s real assets—which, if Barnes’s report is accurate, are not worth much anyway—belong to the Vanuatu company and are located in China, beyond the reach of U.S. law. The company’s prospectus says, “Because our principal assets are located outside of the United States, it may be difficult for investors to use U.S. securities laws to enforce their rights against us.”