I was born the same year as the landmark Supreme Court Brown v. Board of Education took place. Its 60th anniversary is May 17.

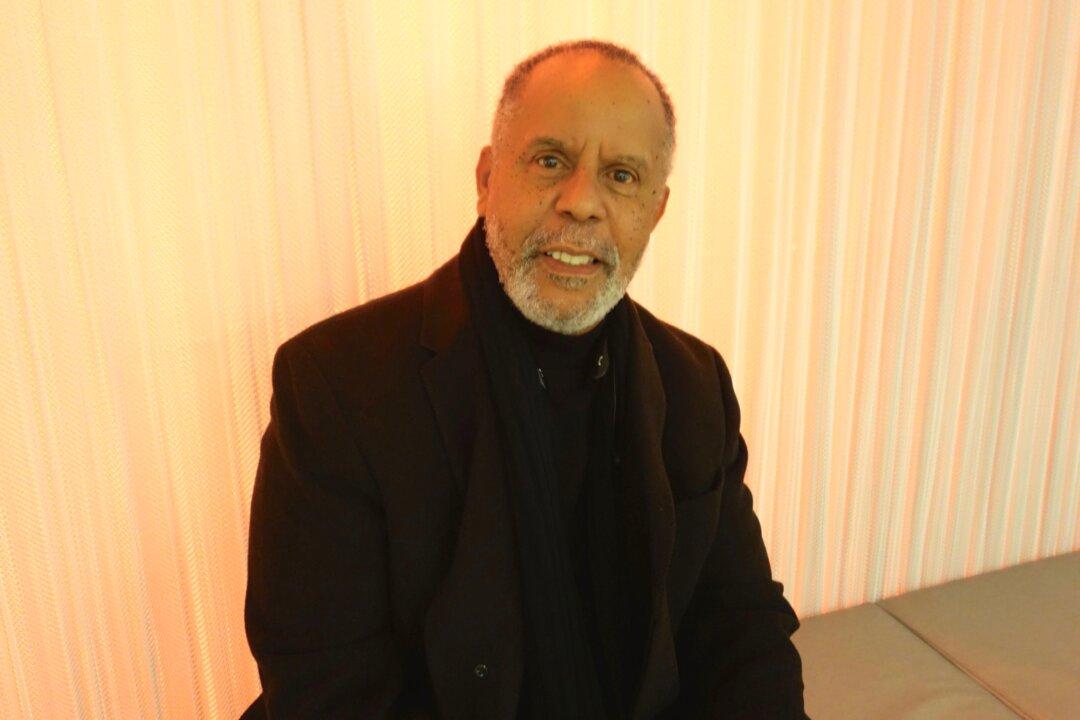

My earliest childhood memories are of a segregated society. Segregation is making a comeback, and that is bad for all students, according to Derek Black, a professor of education, civil rights, and constitutional law at the University of South Carolina. In racially and economically segregated schools, poor students miss the positive peer influence of middle-class students, who have wider vocabularies and aspirations, according to Black. Poor parents lack the resources to influence their neighborhood schools.

Majority students don’t have a chance to develop cultural fluency if every student is just like them. Employers are weary of those who don’t understand and are not comfortable around varied groups, he said.

Black’s description of the culturally unskilled majority person resonated with me. My alma mater, the church-affiliated Lovett School in Atlanta, refused to admit my age mate Martin Luther King III in 1963, nine years after Brown. I remember a trio of priests protesting the decision. They were standing on the bridge over the duck pond on campus, holding placards and wearing formal robes. It’s a snapshot memory, and I cannot confirm it, but I know the headmaster and a board member resigned over the refusal. Now, the thick, glossy, alumni magazine features diverse students on nearly every cover.

It was not until college that I had black classmates. I felt nervous around them, but they were gracious anyway. After we all got to know each other, they made me a little paper crown and inducted me as an honorary black person; they played James Brown at the mock ceremony.

This was the beginning of cultural fluency for me, and I keep trying to fully understand people from different backgrounds to this day.

It’s an important part of anyone’s intellectual development, according to Black.

But the return of segregation deprives people of exposure to peers from different backgrounds. “Once the courts and the government released the pressure in the late 1980s … segregation returned, erasing some of our gains,” said Black.

Underlying Roots

“We have never been able to address … the underlying roots of school segregation. We simply go back to neighborhood schools,” said Black. But neighborhood economic and ethnic segregation is stubborn—and leads to school segregation.

It also leads to poor school quality. In a poor neighborhood, the school will be poor, too. Teachers won’t want to be there, and there will be higher teacher turnover, which disrupts learning for students, said Black.

Places of Privilege

“On top of that we have gated neighborhoods, places of privilege,” said Black. “Unless they are guaranteed schools that meet their standards,” they won’t participate; they will enroll their children in private schools.

What those parents don’t know is that once a school reaches a tipping point of 40 percent to 50 percent middle-income students, the school will be good, because “those parents will set the tone,” said Black. If it’s completely middle income or affluent there is no further gain in educational quality. “It’s running up the score in the fourth quarter.” That completely affluent school does not offer students the benefits of differences, “what we might call the social and employment benefit,” said Black. When confronting a diverse environment, and varied opinions, people learn and stretch. They reason through their assumptions, and they grow, he said.

Black recommends leaving the neighborhood school model behind.

Solution: Regional Schools

Developing a regional school model would allocate resources in a more effective and fairer way, and provide the benefits of diversity, said Black.

Imagine if parents could be more flexible. Imagine you live in the suburbs and work in the city, and there is a good school next to your workplace. In a regional school system, you can enroll your little darlings there, and slip over to the school during lunch.

How great would that be?

It would be entirely great.

Desegregation worked. It can work again.

“I think what’s important to know, is that when we first started integrating schools, we were asked to make a leap of faith,” said Black. “Fifty to 60 years later, the gut instinct” that integration would make education better was proved true.

Benefits for Everybody

“Integrated schools produce academic and social benefits for majority children,” said Black.

Starting with the kindness of the black students at Hollins University, continuing with all the diverse people who are part of my adult life, I’m trying to overcome my early cultural deprivations. Vive la difference!