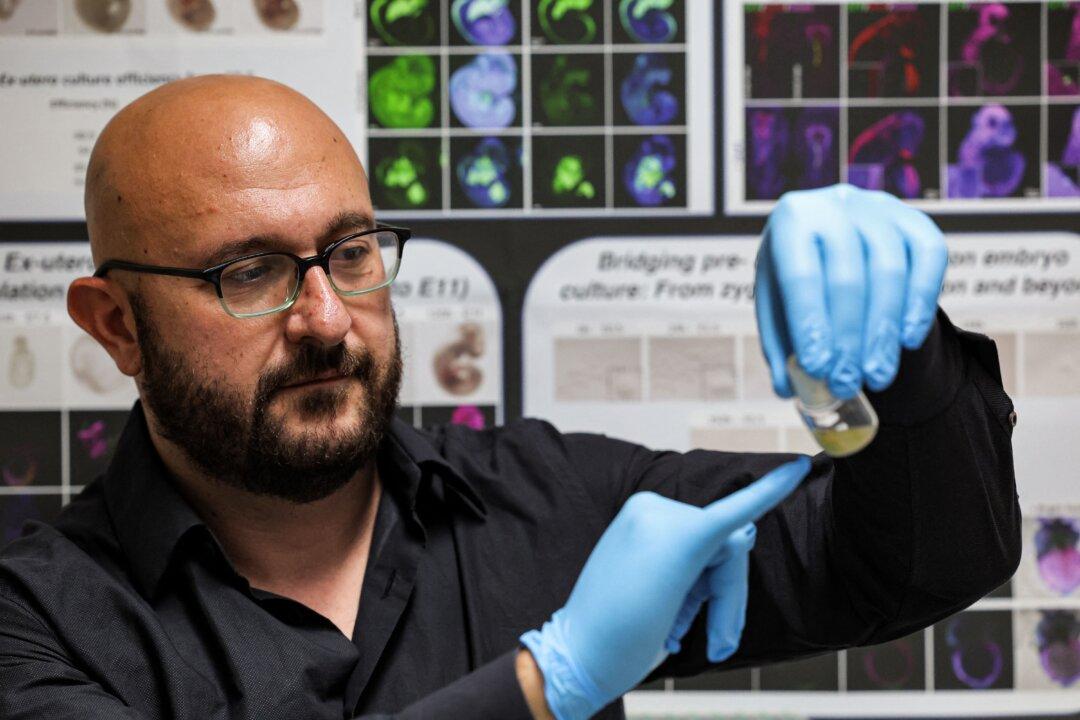

Researchers from Israel’s Weizmann Institute of Science have created complete human “embryo models” without using sperm or eggs, growing them outside of the womb for 14 days.

Embryo models, also known as synthetic embryos, are not equivalent to actual human embryos. Instead, they look similar to early stages of human development but show no signs of the beginnings of a brain or beating heart. Researchers succeeded in creating “embryo models” that were developed from skin cells taken from an adult.