Vladimir Putin’s military buildup in Ukraine poses a challenge for the West, but using force to make a point may prove counterproductive for Putin, analysts say, paving the way for a stronger, more united Ukraine.

Russia amassed 150,000 troops along the border with Ukraine last week in response to the ousting of Ukranian president Viktor Yanukovych. In recent days Ukrainian officials reported that 16,000 Russian troops had been dispersed in key centres throughout Ukraine’s autonomous Crimea region.

Pro-Russian groups have also been witnessed intimidating Ukrainian supporters. In one chilling YouTube video, Ukrainian nationalists in Crimea’s Kharkiv are being hit, kicked and yelled at as they are forced to half walk, half crawl through an abusive pro-Russian crowd.

On March 4, in his first news conference since the crisis began, Mr Putin denied his troops had been active in Ukraine and defended the military buildup. Viktor Yanukovych was the “real leader” he said, describing the installation of the new government as an “anti-constitutional takeover”. All previous treaties, including one respecting Ukraine’s sovereign rights, were annulled, he said. (See transcript.)

Asked about reports of Russian troops blocking access to Ukrainian military facilities, Putin said they were not Russian troops but people dressed up in uniform. “You can go to a store and buy any kind of uniform,” he said.

Putin said any military action would be within the confines of international law and added that Russia reserved the right to use “all means” to protect compatriots who were living in “terror” in Ukraine.

West condemns Putin’s actions

The United States was quick to condemn the statements.

Mr Putin is “not fooling anybody”, said US president Barack Obama.

Speaking in Kyiv on March 4, US Secretary of State John Kerry reinforced the legitimacy of the present Ukrainian Government.

“The Russian Government would have you believe that the Ukraine Government somehow is illegitimate or led by extremists, ignoring the reality that the Rada…, the elected representatives of the people of Ukraine – they overwhelmingly approved the new government,” he said, “even with members of Yanukovych’s party deserting him and voting overwhelmingly in order to approve this new government.”

Ukraine’s government accused Russia of a military invasion and appealed to the international community for help.

“This is the red alert, this is not a threat, this is actually a declaration of war to my country,” said Ukraine’s acting Prime Minister, Arseniy Yatsenyuk, in a televised address from the capital Kyiv March 2.

Professor Felix Patrikeeff, an expert in post socialist Russia at the University of Adelaide, said help may not be so forthcoming.

While western countries have been united in their condemnation of Putin’s actions, an emergency meeting of NATO members March 4 highlighted divisions on how to respond.

“We have a situation where the West is very unlikely to intervene with anything other than words of caution and words of reprimand,” and perhaps some economic or “broad, institutional, political measures”, Dr Patrikeeff said in a phone interview.

Ukraine a core interest

Ukraine is considered to be a heartland of old Russia, the centre of the early Kievan Rus’ and home to Vladimir the Great and the Cossack Republic.

Ukraine gained independence in 1991 following the collapse of the Soviet Union, but still contains a large population of ethnic Russians, particularly in Crimea where Russians comprise 59 per cent of the autonomous region’s 2 million population, according to a 2001 census.

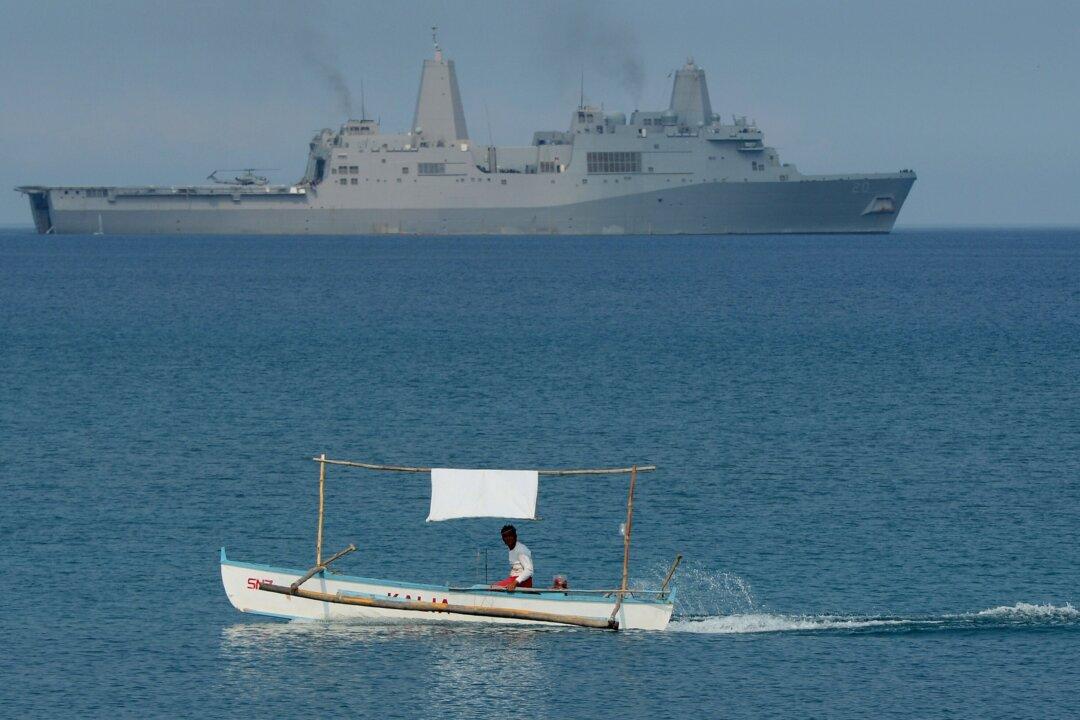

Crimea’s importance is heightened by the presence of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet which is harboured in Sevastapol under a lease agreement with the Ukrainians. That agreement was extended to 2042 in 2010 by Yanukovych in exchange for discounted natural gas.

“Russia’s big power polity is actually measured by all the countries close to it,” said Dr Patrikeeff. While it is difficult to predict what the outcome may be, Ukraine’s “core interest” to Russians will heighten what is already a predilection for force rather than negotiation.

“Russia’s approach has consistently been ‘if we strike we are going to strike hard and we are going to strike effectively and after that we talk’,” he said.

Dr John Besemeres, an expert in Russia and Eastern Europe at the Australian National University, believes strong military action by Putin could backfire.

Independent media in Russia are expressing concerns that Putin may be risking Russia’s influence in the region, he said. They warn that if Putin goes too far he will create a strong backlash from Nationalist Ukrainians which could threaten the status of Russia’s military facilities in the region.

“It is hard to deny the logic of that,” he said in a phone interview.

While western Ukraine is traditionally considered pro-European, and eastern and south eastern regions considered more pro-Russian, the Russian ethnic population overall is only around 17 per cent of Ukraine’s 45 million population and allegiance to Russia is changing.

Russia’s attitude to the Ukraine has traditionally been “very patronising”, more like “country cousins”, said Dr Besemeres but recent polls indicate more and more Russian speakers identify as Ukrainians.

“The strength of the Ukraine, as a state, has increased over time,” he said.

Ukraine’s future

It was also Viktor Yanukovych’s back-down on increasing engagement with Europe in favour of quick funds and political support from Vladimir Putin’s Russia, that precipitated his ousting and what is now known as the Maidan Revolution.

Ukraine is due to hold national elections in May and while there is much cynicism about the 23 political candidates, Dr Besemeres remains positive.

Many politicians are tainted with allegations of corruption, including former prime minister Yulia Tymoshenko, but he believes there is still potential.

Vitali Klitschko, leader of the Ukrainian Democratic Alliance for Reform and a former professional boxer, is one politician untainted by corruption and has been shown to be acceptable to voters in the East, he said.

He also cites, Petro Poroshenko, a former Foreign Minister and a former head of Ukraine’s National Bank, as someone with valuable experience.

He believes with Western support, there is a good chance a new Ukrainian government can unite the country and work towards overcoming its considerable economic and political problems.

“If the West can pony up some serious millions [of dollars] and, together with the IMF, produce a rescue package, I think that would greatly increase the popularity of this fragile government and appease many of those harsh critics,” he said.