News Analysis

In the week leading up to the Obama-Hu press conference the administration’s Cabinet secretaries had, one after another, laid out clear expectations for a shift in China’s stance on key issues. At the press conference, these specific proposals for a new U.S.-China relationship were scarcely acknowledged.

Perhaps the most interesting part of the press conference was seeing journalists press Chairman Hu Jintao on human rights abuses under communist rule in China. The way that Mr. Hu responded to those two questions—by not addressing them substantively at all—was a good indication of how the conference as a whole went.

“These things are always rather lackluster and pallid,” said Dean Cheng of the Heritage Foundation’s Asian Studies Center in a telephone interview.

“If you go in with no clear objective, and you go in somewhat rudderless, then in that case what you will get out on the other side is probably going to be somewhat rudderless and somewhat lackluster.”

The hour-long event started with readings from prepared statements by both sides. Each understood the others’ views, agreed that cooperation was essential, and reaffirmed how the Sino-U.S. relationship was of utmost importance. Throughout the discussion these ideas were continually repeated in different ways.

But when it came to the key issues that Secretaries Clinton, Locke, and Geithner had hammered away at last week—human rights, the undervalued yuan, protecting intellectual property, North Korea, China respecting international rules of navigation, China becoming more like a market economy, ceasing mercantilist business practices, and so on—there were no hard commitments.

The human rights issue was brought up twice, the first time Chairman Hu apparently having missed the question. He said that China was all for human rights, and that the country has made “enormous progress, recognized widely in the world.” Of course, to anyone who follows the issue both these statements are obviously untrue.

No commitments were made on North Korea, or on maritime navigation, currency manipulation, the market-economy problem, the mercantilist-business-practices problem, or the intellectual-property-theft problem.

The chairman did make the commitment that American companies would no longer be discriminated against when it comes to competing for Chinese government procurement contracts, but following through in this area will no doubt be difficult. In China, where corruption is ubiquitous, many such contracts are awarded to state-owned enterprises or to firms that give kickbacks to regulators. The Communist Party’s overriding goal is domestic stability, so it is unclear how an established business culture of this sort—which keeps many in the Party very comfortable—will be easily disrupted.

Chairman Hu had clearly been briefed on the administration’s previous statements. He made reference to the idea that, as Clinton put it, “When you’re in the same boat, you have to row in same direction … or we will cause turmoil and whirlpools that will affect many beyond our borders.”

But principally, viewers were treated to a recitation of positive sentiments about the U.S.-China relationship. At certain points one could have swapped President Obama and Chairman Hu’s remarks and no one would have been the wiser.

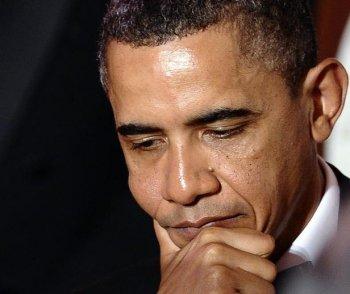

At one point, President Obama said, “I absolutely believe that China’s peaceful rise is good for the world,” then changed it to “And finally, China’s rise is potentially good for the world.”

The second statement was qualified upon China’s “functioning as a responsible actor on the world stage,” “ensuring that weapons of mass destruction don’t fall into the hands of terrorists or rogue states,” and “helping poorer countries in Asia or in Africa further develop.”

But a look at the record indicates that the Chinese Communist Party has been responsible for the proliferation of nuclear and other weapons to fringe or rogue states, where they are most likely to fall into the hands of terrorists, and what appears to be help to poor countries is often the opposite.

This disjuncture between rhetoric and reality can only be resolved by time.

“Summits, for the most part, are almost like kabuki,” said Dean Cheng of Heritage Foundation. “Or like going to see another production of Gilbert and Sullivan: we all know the lyrics, we all know the tunes.”

The question is, Cheng says, whether in six months from now there will have been an appreciable change in Chinese policy. “The real proof in the pudding is going to be, after all this is over, after all the bunting is taken down, will the United States hold the Chinese accountable.

“Will they be consistent about it, will they be persistent about it, will they be firm about it?”

Email: [email protected]