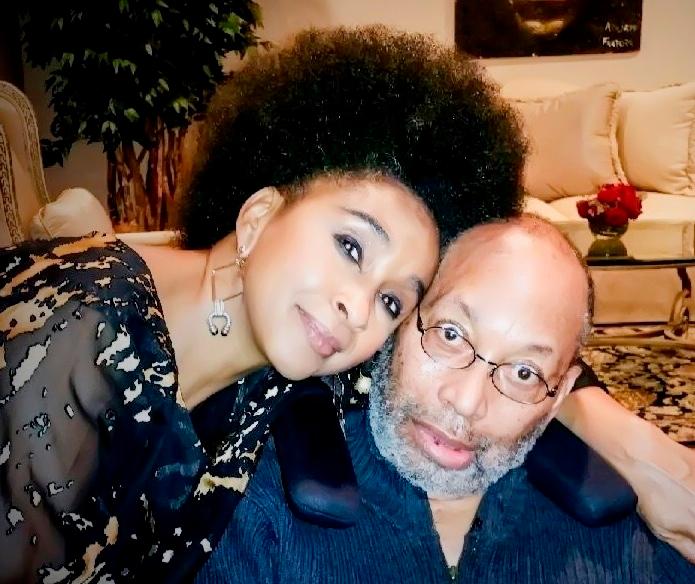

SAN DIEGO—As the November presidential election neared, it looked like David Rector would once again be unable to vote. Five years ago, a judge ruled that a traumatic brain injury disqualified him.

Then the 66-year-old former NPR producer learned about a California law that makes it easier for people with developmental disabilities to keep and regain the right to vote. The law, which took effect Jan. 1, protects that right if they can express a desire to vote.