NEW YORK—The brightly painted blue and green hallways at Achievement First Bushwick, a charter school in Brooklyn, contrast sharply with the thick, dull tiles that cover the walls of I.S. 383, the public school it shares a building with.

If Mayor Bill de Blasio puts his campaign promise into action, one of these public schools, and not the other, will have to pay rent.

“It makes me nervous,” said Mike Rosskamm, principal of Achievement First Bushwick. By one estimate, his school could be looking at more than $850,000 a year in rent.

“Charging rent would take a big hit out of our budget, and would not allow us to serve our kids in the way we’re serving them now,” said Rosskamm.

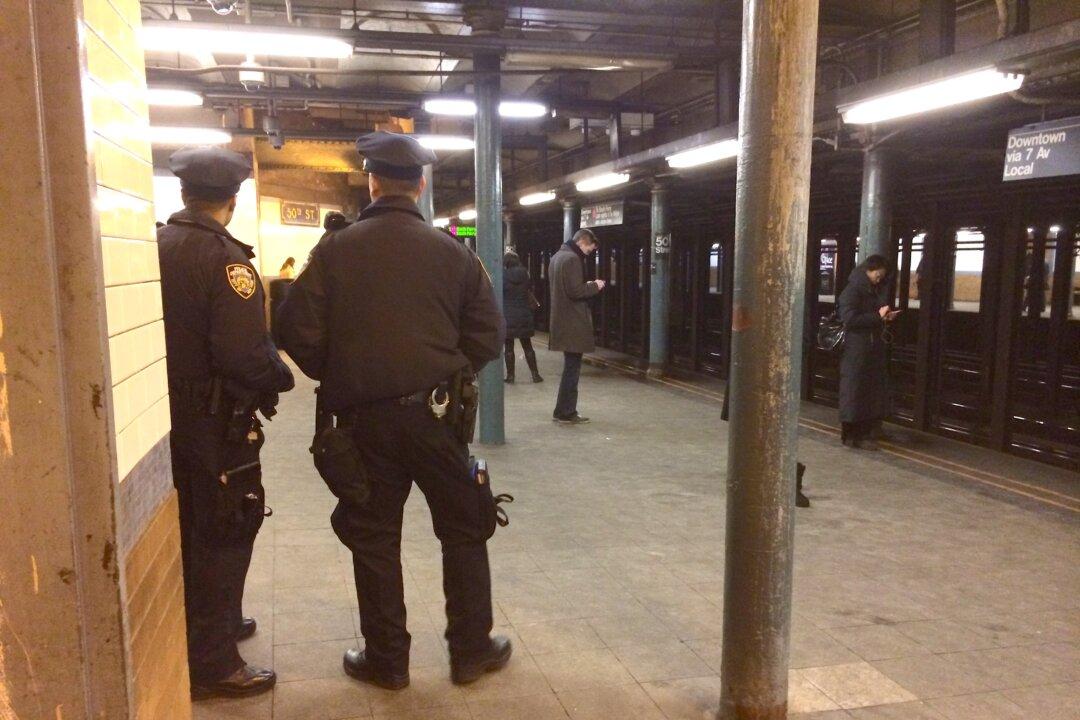

Achievement First Bushwick teaches 370 students in grades five–eight. They occupy most of the fourth floor of a large red brick building near the Knickerbocker Avenue stop on the M subway line. I.S. 383, whose principal declined to comment for this story, occupies floors one through three. The two co-located schools share an auditorium, cafeteria, gym, and playground.

Achievement First Bushwick students perform well. They scored an average of 73 percent on New York state’s 2012 standardized tests. This compares to 37 percent for students in the local public school district (District 32), a low-income, mostly black and Hispanic neighborhood.

“There’s a high demand for schools like our school, specifically, because we’re doing really, really well in this community, especially relative to the district. And so parents are really invested in trying to get their students into school here,” said Riley Bauling, academic dean at Achievement First Bushwick.

Achievement First Bushwick is funded with public money from the city, state, and federal governments, just like regular public schools. It also receives some private philanthropic funding. As is required by law, it has no academic requirements for admission. Instead, it accepts students through a lottery, weighted in favor of children from the neighborhood. Most of its students started at an Achievement First elementary school, and moved up through its system.

Clive Campbell is one of those students. He is in the fifth grade now, and has attended Achievement First schools since kindergarten.

Clive said he doesn’t mind the long school days, which start at 7:30 a.m. and end at 4 p.m.

“I like the learning that we do and the teachers,” said Clive. “If we don’t understand it, they’ll help us.”