Pterosaurs, the large flying reptiles that existed between 220 million and 65 million years ago, flew best when the weather was mild, tropical, and breezy—but would have crashed to earth in stormy weather, concludes new research published online last week in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

The flying reptiles, also known as pterodactyls, were too flexible and didn’t have strong enough bones to make use of strong winds, says study author Colin Palmer. As a result, pterosaurs most likely soared gently on thermal air currents.

Palmer, an engineer for 40 years who is now a paleontology Ph.D. student at the University of Bristol in the U.K., made a model of the ancient reptile’s wings out of an epoxy resin/carbon fiber composite and tested the model in a wind tunnel.

He found that the wings were less aerodynamic than previously thought and best suited for low-speed flight that “minimizes sink rate,” or rate of descent.

“[Their wings are] unsuited to marine-style dynamic soaring adopted by many seabirds which requires high flight speed coupled with high aerodynamic efficiency, but is well suited to thermal/slope soaring,” he said in a news release from the university.

“The low sink rate would have allowed pterosaurs to use the relatively weak thermal lift found over the sea.”

Their bones also have thin walls, so low-speed flying and landing would have been optimal to minimize damage, he added.

“The trade-off would have been an extreme vulnerability to strong winds and turbulence, both in flight and on the ground, like that experienced by modern-day paragliders,” Palmer said.

However, some scientists question Palmer’s conclusions.

“I think the overall membrane dynamics he’s looking at are very good,” Dr. Michael Habib, a pterosaur expert at Chatham University in the United States, told Scientific American. “But I’m a little skeptical of their extreme vulnerability to turbulence and strong winds.”

Habib added that pterosaurs could have more muscle control over the wings than Palmer is giving them credit for, which would mean the reptiles would have been able to handle stronger winds.

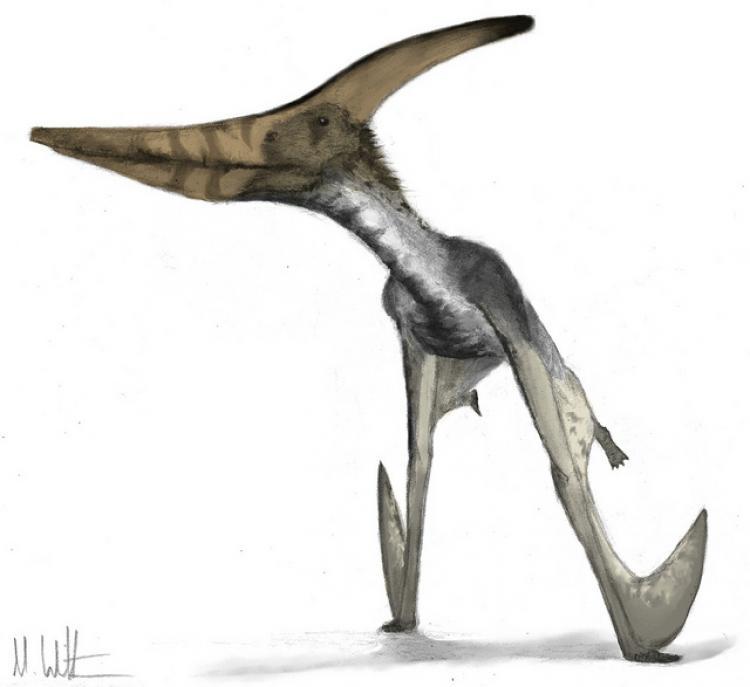

Earlier this month, Habib and Dr. Mark Witton from the University of Portsmouth, U.K., published evidence in the journal PLoS ONE that pterosaurs were skilled at flying and could travel long distances, refuting recent claims that giant pterosaurs were flightless.

“Most birds take off either by running to pick up speed and jumping into the air before flapping wildly, or if they’re small enough, they may simply launch themselves into the air from a standstill,” Witton explained in a press release.

“Previous theories suggested that giant pterosaurs were too big and heavy to perform either of these maneuvers and therefore they would have remained on the ground.

“But when examining pterosaurs, the bird analogy can be stretched too far. These creatures were not birds; they were flying reptiles with a distinctly different skeletal structure, wing proportions and muscle mass. They would have achieved flight in a completely different way to birds and would have had a lower angle of take off and initial flight trajectory. The anatomy of these creatures is unique.”

They propose instead that pterosaurs used their four limbs to launch themselves into the air, pushing themselves up into the air using their powerful arm muscles, which account for 20 percent of the reptiles’ body mass.

“By using their arms as the main engines for launching instead of their legs, they use the flight muscles—the strongest in their bodies—to take off, and that gives them potential to launch much greater weight into the air,” said Habib in the press release.

Based on their research, Habib and Witton believe the largest pterosaurs were not as big as previously estimated, so they were also lighter overall.

“Weight estimates based on a 12-meter [39-foot] wingspan will be almost twice that based on 10 meters, so an accurate assessment is vital,” Witton said.

In contrast to Palmer’s conclusions, Habib and Witton believe pterosaurs had strong bones for their weight, and wings reinforced with strong flight muscles that allowed them to flap and soar—they may even have been capable of flying across continents.

“All the direct data we have on pterosaurs, even the largest, suggests they were capable of flying,” Witton concludes.

The flying reptiles, also known as pterodactyls, were too flexible and didn’t have strong enough bones to make use of strong winds, says study author Colin Palmer. As a result, pterosaurs most likely soared gently on thermal air currents.

Palmer, an engineer for 40 years who is now a paleontology Ph.D. student at the University of Bristol in the U.K., made a model of the ancient reptile’s wings out of an epoxy resin/carbon fiber composite and tested the model in a wind tunnel.

He found that the wings were less aerodynamic than previously thought and best suited for low-speed flight that “minimizes sink rate,” or rate of descent.

“[Their wings are] unsuited to marine-style dynamic soaring adopted by many seabirds which requires high flight speed coupled with high aerodynamic efficiency, but is well suited to thermal/slope soaring,” he said in a news release from the university.

“The low sink rate would have allowed pterosaurs to use the relatively weak thermal lift found over the sea.”

Their bones also have thin walls, so low-speed flying and landing would have been optimal to minimize damage, he added.

“The trade-off would have been an extreme vulnerability to strong winds and turbulence, both in flight and on the ground, like that experienced by modern-day paragliders,” Palmer said.

However, some scientists question Palmer’s conclusions.

“I think the overall membrane dynamics he’s looking at are very good,” Dr. Michael Habib, a pterosaur expert at Chatham University in the United States, told Scientific American. “But I’m a little skeptical of their extreme vulnerability to turbulence and strong winds.”

Habib added that pterosaurs could have more muscle control over the wings than Palmer is giving them credit for, which would mean the reptiles would have been able to handle stronger winds.

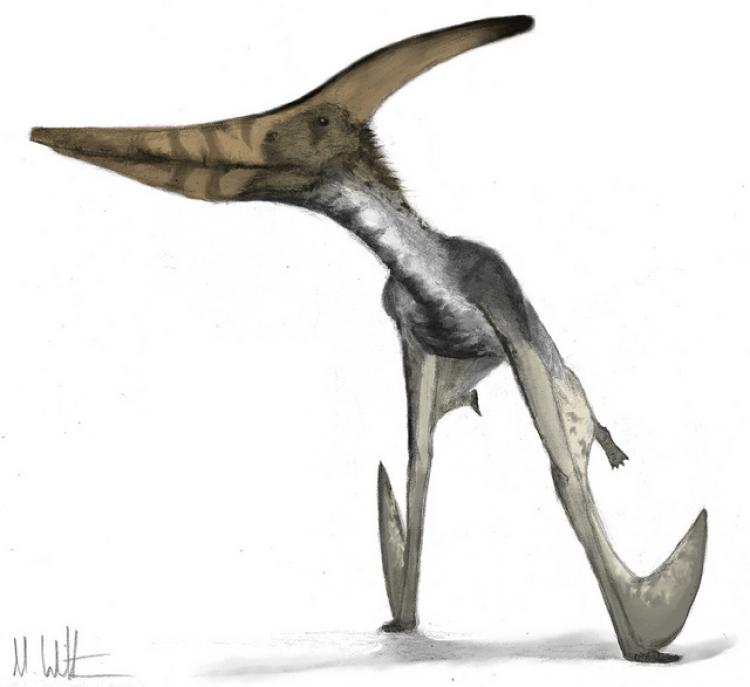

Earlier this month, Habib and Dr. Mark Witton from the University of Portsmouth, U.K., published evidence in the journal PLoS ONE that pterosaurs were skilled at flying and could travel long distances, refuting recent claims that giant pterosaurs were flightless.

“Most birds take off either by running to pick up speed and jumping into the air before flapping wildly, or if they’re small enough, they may simply launch themselves into the air from a standstill,” Witton explained in a press release.

“Previous theories suggested that giant pterosaurs were too big and heavy to perform either of these maneuvers and therefore they would have remained on the ground.

“But when examining pterosaurs, the bird analogy can be stretched too far. These creatures were not birds; they were flying reptiles with a distinctly different skeletal structure, wing proportions and muscle mass. They would have achieved flight in a completely different way to birds and would have had a lower angle of take off and initial flight trajectory. The anatomy of these creatures is unique.”

They propose instead that pterosaurs used their four limbs to launch themselves into the air, pushing themselves up into the air using their powerful arm muscles, which account for 20 percent of the reptiles’ body mass.

“By using their arms as the main engines for launching instead of their legs, they use the flight muscles—the strongest in their bodies—to take off, and that gives them potential to launch much greater weight into the air,” said Habib in the press release.

Based on their research, Habib and Witton believe the largest pterosaurs were not as big as previously estimated, so they were also lighter overall.

“Weight estimates based on a 12-meter [39-foot] wingspan will be almost twice that based on 10 meters, so an accurate assessment is vital,” Witton said.

In contrast to Palmer’s conclusions, Habib and Witton believe pterosaurs had strong bones for their weight, and wings reinforced with strong flight muscles that allowed them to flap and soar—they may even have been capable of flying across continents.

“All the direct data we have on pterosaurs, even the largest, suggests they were capable of flying,” Witton concludes.