Commentary

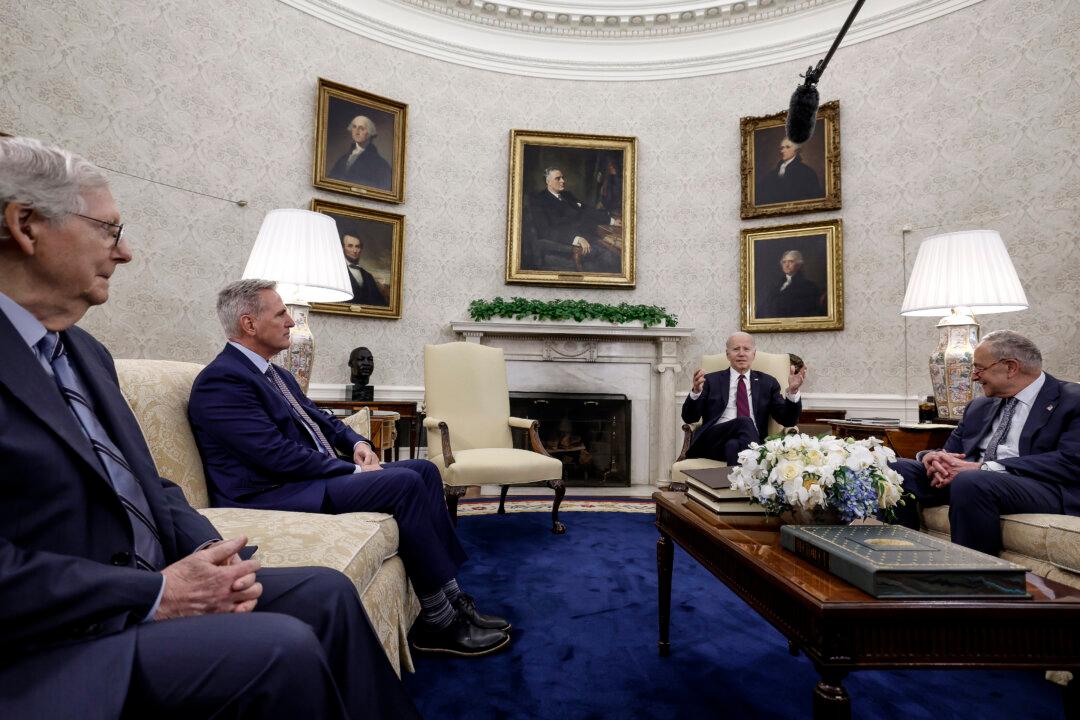

Let’s get one thing off the table. Putting aside the Biden administration’s fear-mongering, the U.S. government won’t substantively default on its debt in June 2023. The game of high-stakes chicken being played right now with congressional leadership will resolve before it’s too late. In brief, the administration and Democrat leadership want to raise the debt ceiling, no questions asked. Republican leadership insists, not unreasonably, that there must be spending cuts. The question is, who blinks first? Given the alternative is financial markets Armageddon, a compromise will be reached. So everything is fine. Right?