Commentary

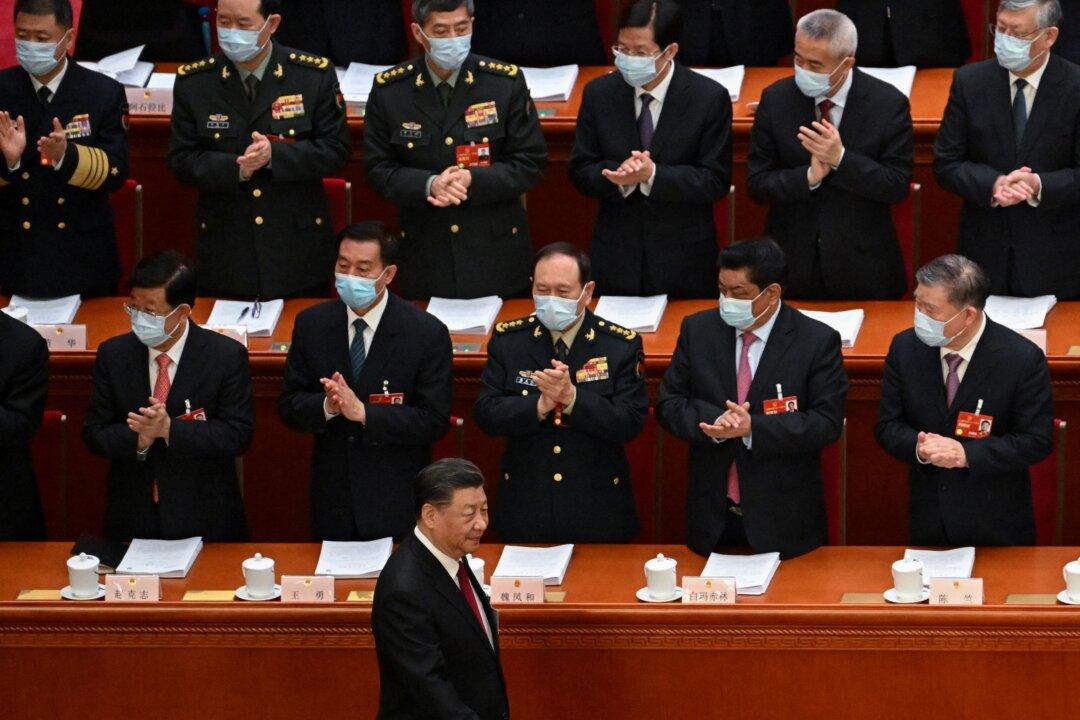

There’s every reason to suspect that Chinese communist leader Xi Jinping has more political difficulty than he can manage. But what if he succeeds in managing these threats to his position?

There’s every reason to suspect that Chinese communist leader Xi Jinping has more political difficulty than he can manage. But what if he succeeds in managing these threats to his position?