Commentary

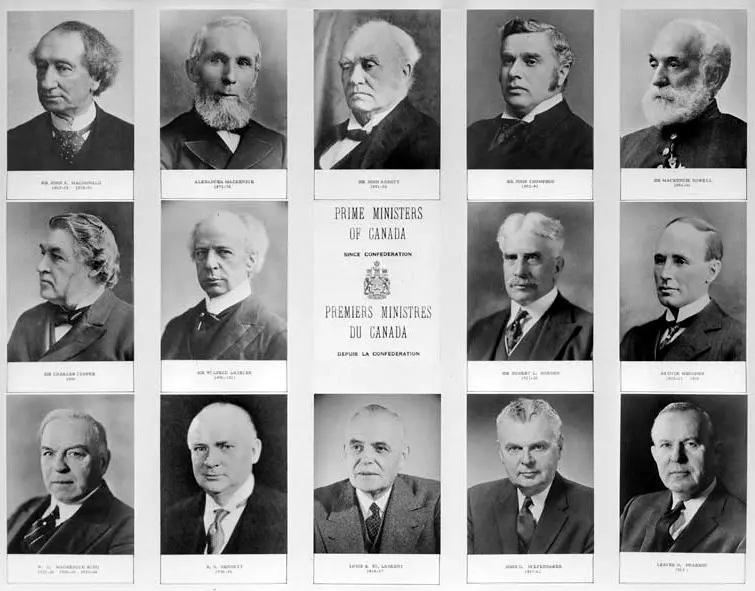

John George Diefenbaker was the first Prime Minister of Canada (1957–1963) with a name and lineage neither British nor French. His grandfather, George Diefenbacher, came from Baden in Germany, although his mother’s side was Highland Scots. He had been mocked as a “Hun” during his youthful campaigns in Saskatchewan, so he knew what it was like to be picked on because of his name and race. And so Diefenbaker put himself on the side of the “little guy” and it took him a long way.