Commentary

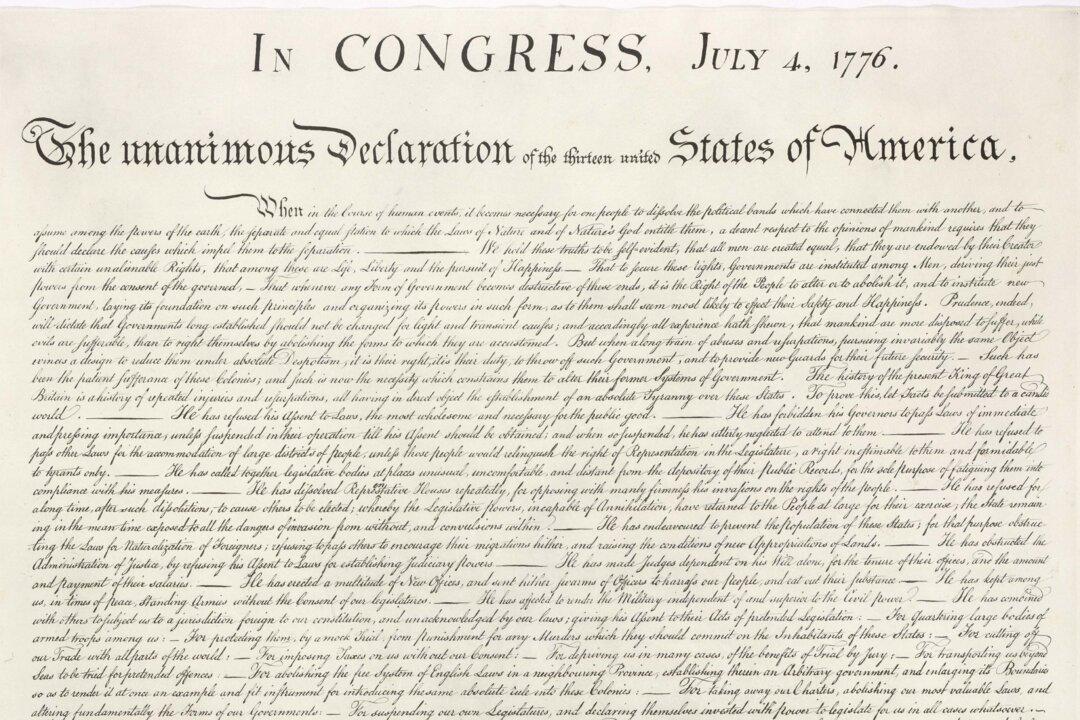

Mike Johnson opened his tenure as speaker of the House with a speech citing the creator God mentioned in the Declaration of Independence. The speech drew criticism from columnists in The Washington Post, Time, PBS, and The New York Times, among others. Much of it shifted among Mr. Johnson’s support of former President Donald Trump, his church affiliations, and his penchant for employing biblical language.