Commentary

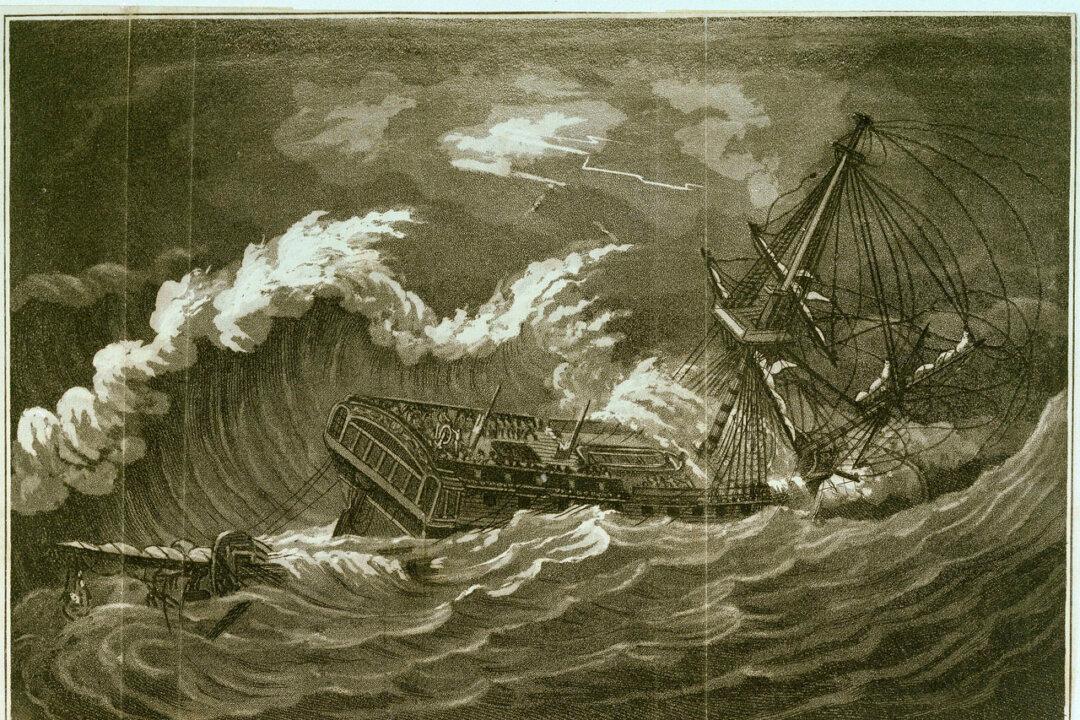

Ships of Britain’s massive Royal Navy, the largest in the world, inflicted great damage on American ports, property, and vessels during the years of the Revolution (1775–1783). Perhaps none of those ships wreaked more havoc than HMS Phoenix, and it accomplished its devious work not with a cannon but with a printing press.