In the northeastern Indian state of Assam, a 51-year-old man lives with his family in a small hut without electricity or a water connection, isolated from the hubbub of nearby cities. Jadav “Molai” Payeng, a member of Assam’s indigenous Mising tribe, resides in Assam’s Jorhat district in the village of Aruna Chapori. Here, for the past 35 years, he has worked to plant trees on a sandbar island in the river near his home—and in the process, single-handedly established a forest larger than New York City’s Central Park now home to tigers, rhinos, and elephants.

One of Asia’s mightiest rivers, the Brahmaputra, flows through the state of Assam. Every year, tumultuous monsoon rains cause the river to swell in a cycle that results in natural flooding. However, these events may be worsened by deforestation along and near the river. Without trees to uptake the excess water, more is released into the water system. Without tree roots to hold the soil together, riverbanks can erode and a river’s water may become choked with silt, threatening species that evolved to live in clearer water. For the Brahmaputra, deforestation may be lending a hand to catastrophic floods that have caused severe losses of life and property. For instance, in 2012 at least 124 people were killed by flooding of the Brahmaputra and six million displaced, with 540 recoded animal deaths at Kaziranga National Park just downstream from Jorhat – including 13 Indian rhinoceroses (Rhinoceros unicornis).

As a teenager, Payeng lived in Jorhat’s Kokilamukh area, on the banks of the river. It was there, one day in 1979, where he witnessed scores of dead snakes that been washed ashore on a large sandbar by the flooded Brahmaputra. It was a sight that changed his life.

“The snakes died in the heat, without any tree cover,” Payeng told The Times of India. "I sat down and wept over their lifeless forms. It was carnage.

“I alerted the forest department and asked them if they could grow trees there. They said nothing would grow there. Instead, they asked me to try growing bamboo,” he said. “It was painful, but I did it. There was nobody to help me. Nobody was interested.”

The experience had a lasting impact on Payeng. In 1980, the social forestry division of the state’s Golaghat district launched a five-year tree plantation scheme to fight rapid soil erosion on 200 hectares of land at Aruna Chapori – located five kilometers from Kokilamukh. “Molai Kathoni,” as Payeng is fondly referred to, started working on this project as a laborer.

The five-year project was abandoned in three years when the laborers packed up and left. Payeng, however, chose to stay on and took it upon himself to single-handedly plant seeds and saplings over 550 hectares of land on the sandbar. He left his education and home in Kokilamukh to live on the sandbar, willingly accepting a tough life of isolation. Alone, he tended to plants while planting more along the way until the sandbar eventually turned into a bamboo thicket.

“I then decided to grow proper trees,” Payeng told the Times of India. “I collected and planted them. I also transported red ants from my village and was stung many times. Red ants change the soil’s properties. That was an experience,” he said, laughing.

And transform the sandbar he did. Today, his efforts have created and sustained a 550-hectare forest – the Molai forest – named after Payeng’s nickname.

However, Payeng’s relentless efforts were only noticed by the Assam state forest department in 2008 when officials went into the region in search of over 100 wild elephants that had retreated into the forest after damaging property in the Aruna Chapori village, one and a half kilometers from the Molai forest. The elephants had also destroyed Payeng’s settlement.

That was when Assistant Conservator of Forests, Gunin Saikia, met “Molai” Payeng for the first time.

“We were surprised to find such a dense forest on the sandbar,” Saikia said. “Locals whose homes had been destroyed by the pachyderms, wanted to cut down the forest but Payeng dared them to kill him instead.”

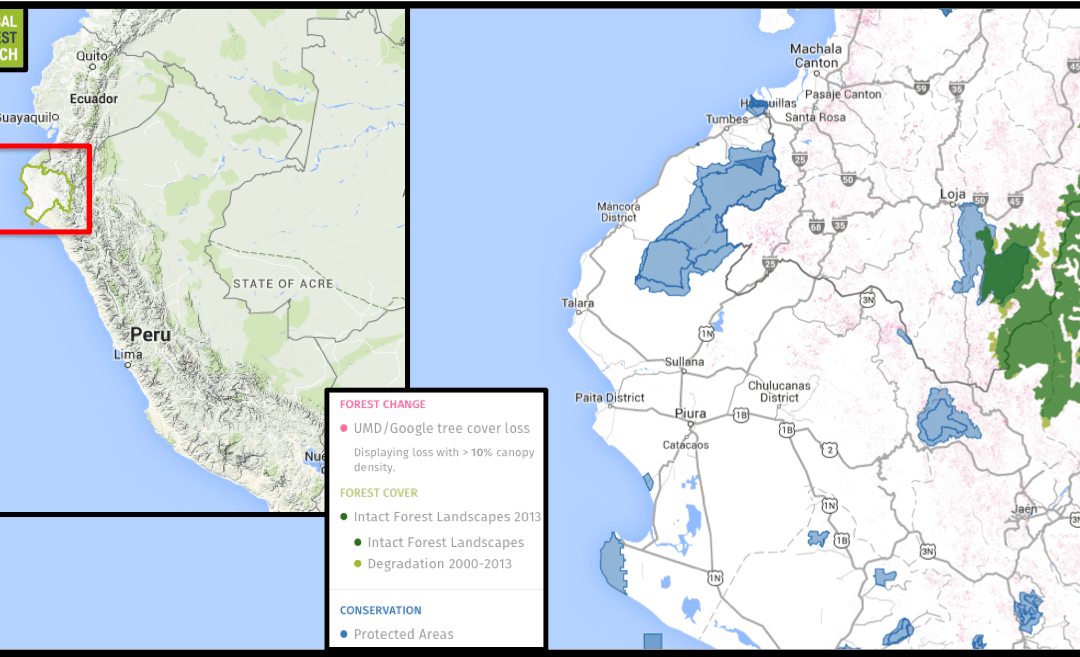

Data from Global Forest Watch reveals that in 2012, the state of Assam lost 13,684 hectares of forest cover. Overall, between 2001 and 2013, the state lost more than 132,000 hectares of tree cover—or more than 4 percent of its densely forested land.

The world’s first man-made forest on a sandbar, the Molai forest, according to Saikia, may also be the world’s biggest forest in the middle of a river.

The forest is now home to some of Asia’s most iconic and threatened species including the Endangered Bengal tiger (Panthera tigris), the Indian rhinos listed as Vulnerable by the IUCN, the Endangered Asian elephant (Elephas maximus), hundreds of deer, vultures and scores of other birds. Several thousand species of trees can also be found in the Molai forest today while over 300 hectares of its expanse is bamboo-covered. Not only does this forest provide a safe haven for wild animals, it is now also a breeding ground for them. In recent years, a herd of about 100 elephants that regularly visits the forest has reportedly given birth to at least 10 calves. Reports from 2012 indicate that one of at least five tigers inhabiting Payeng’s forest has given birth to two cubs.

“After 12 years, we have seen vultures. Migratory birds, too, have started flocking here. Deer and cattle have attracted predators,” Payeng said.

But where there’s a paradise, dangers are often just around the corner. A few years ago, poachers attempted to kill rhinos in the Molai forest. When Payeng notified forest officials, the plan was foiled and traps were seized from the poachers.

The man who single-handedly transformed barren land into a self-sustaining forest lives the life of a social outcast. Threatened by people in his own village, illegal loggers and poachers, Payeng, his wife Binita and their three children live in exile in the primitive hut they now call home.

His only source of income is the money he makes by selling milk from his cattle. Payeng recently shared that he lost around 100 cows and buffalo to the tigers in his forest. But he blames the people moving into and clearing forests as the root cause of the predation.

“Nature has made a food chain; why can’t we stick to it?” Payeng said. “Who would protect these animals if we, as superior beings, start hunting them?”

Citations:

- Hansen, M. C., P. V. Potapov, R. Moore, M. Hancher, S. A. Turubanova, A. Tyukavina, D. Thau, S. V. Stehman, S. J. Goetz, T. R. Loveland, A. Kommareddy, A. Egorov, L. Chini, C. O. Justice, and J. R. G. Townshend. 2013. “UMD Tree Cover Loss and Gain Area.” University of Maryland and Google. Accessed through Global Forest Watch on 13 November 2014.

This article was originally written and published by Apoorva Joshi, a correspondent author for news.mongabay.com. For the original article and more information, please click HERE.