NEW YORK—Community schools offer the promise of higher test scores, better attendance, fewer suspensions, and healthier children.

The schools are a little talked about part of Mayor Bill de Blasio’s education plan, but they are consistent with his commitment to reducing inequality. De Blasio’s goal is to create 100 new community schools in high poverty neighborhoods by the end of his first term.

It takes hard work and a lot of money to create a good community school, and more of the same to keep it running. Unlike his prekindergarten plan, which he proposes to pay for with a tax on the city’s wealthiest households, de Blasio has yet to clarify how the new community schools would be funded.

Requests to the mayor’s office for comment were forwarded to the city’s Department of Education. DOE spokesman Harry Hartfield said in an email response, the department hopes to develop the schools “with coordination between city agencies and our partners in the community.” He didn’t elaborate on any funding plans.

De Blasio has praised community schools as “epicenters of community.” The city already has more than 100 of them partnering with local organizations to provide extra services within the walls of existing public schools.

These may be after-school dance lessons, home finance workshops for parents, or full-fledged medical centers.

The extra services cost about a million dollars a year to operate. Some community schools are able to secure up to 65 percent of their funding from state and federal grants.

Successful community schools require not only funding, but also strong community engagement. Parents volunteer, school staff helps after hours, and nonprofit service providers on limited budgets find creative ways to bring in additional instructors.

Finding the money is not necessarily a problem, since creating more community schools is more a question of priorities, according to David Bloomfield, professor of educational leadership, law, and policy at Brooklyn College.

“The money is probably there, but in different pockets,” Bloomfield said. “It takes vast bureaucratic cooperation, which always seems difficult for the city to accomplish.”

Successful Model

Salomé Ureña de Henríquez Campus Community School serves students from low-income families in West Harlem. Ninety percent of the students in the building qualify for free lunch, according to the DOE.

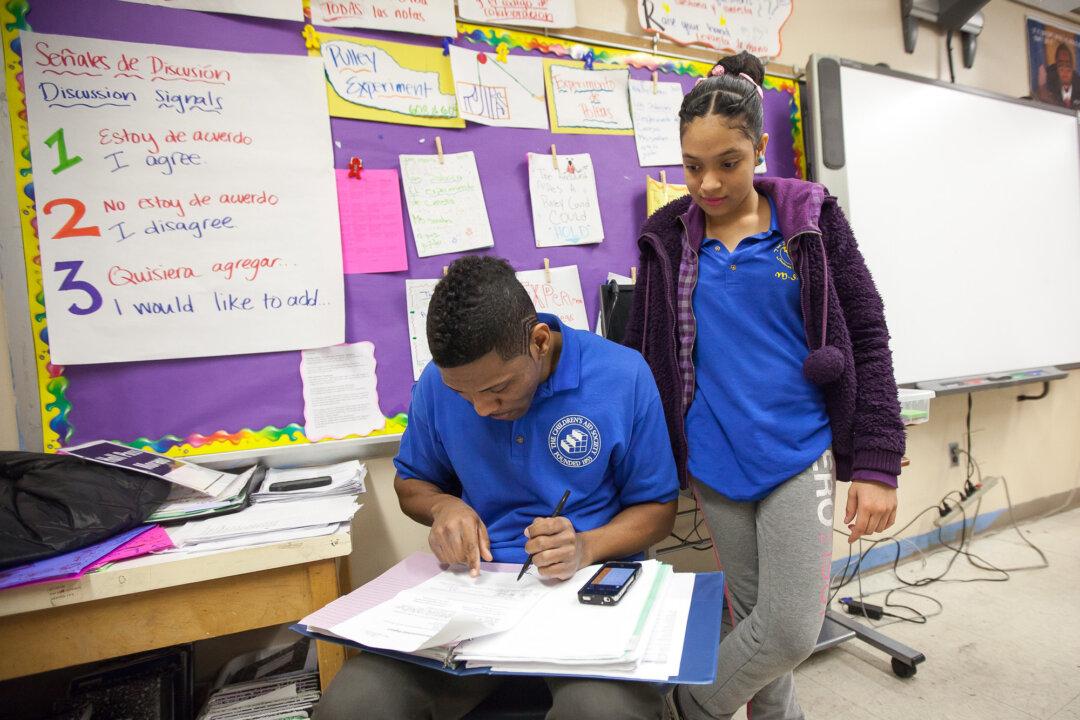

Salomé Ureña’s community school program is run by the nonprofit Children’s Aid Society (CAS). It offers extensive after-school activities, personal tutoring, parent workshops, and a medical center with a full-time physician. A dentist and psychiatrist are available twice a week.

Migdalia Cortes-Torres, the director of the community program, is fluent in Spanish, a must in a school with a 95 percent Latino population.

Whether it’s a medical problem, after-school issue, or an unhappy parent, Cortes-Torres knows who to call to fix it.

“I’m the person that everyone comes to see,” she said.

At the same time she needs to be a savvy manager.

“We’re very creative with funds,” Cortes-Torres said, pointing to a 50-inch LCD in the parent room. “You see this television? That was a donation.” The media stand under it was bought through parents’ fundraising.

The CAS has built a strong reputation in the community over the 21 years it has been operating at Salomé Ureña, Cortes-Torres said, adding that both parents and school leaders trust it.

She said the trust helps a lot with hiring. Since the school can’t offer high salaries, or even full-time salaries, the community school program partly relies on its prestige to attract and keep good personnel.

The community school program at Salomé Ureña has 55 staff members. Only five are full-time employees, while the rest work part-time. Close to 40 percent of the staff are college students. Others include local teachers who stay after regular school hours.

Despite its extensive services, the community part of the school can only accommodate a portion of its 1,300 students. After-school programs serve 280 children; the family room, where parents can come anytime and attend workshops in the evening, is usually packed.

The only service available to, and used by, almost everyone, is the medical center, which tends to over 50 children every day. It is also separately funded through Medicaid insurance.

Expansion

Jane Quinn, CAS vice president for community schools, said CAS has some untapped potential for expansion, but she couldn’t estimate how many more community schools the organization would be able to establish. She said CAS could offer guidance to other organizations on how to establish and run the programs.

The CAS runs 16 community school programs in the city. Six of them provide the full range of services, including a health center. Most other community schools in the city are called Beacons.

Beacons are funded directly by the city, but offer a more limited array of services. Many struggle financially. The city funds each with $340,000 a year.

According to Cortes-Torres, private funding has been hard to come by over the last few years. Quinn hopes the city will provide more to fill the funding gaps.

Bloomfield said de Blasio may have endorsed community schools partly to “curry favor with the teachers union,” but he thinks the mayor can still deliver on his promise since he has executive power over the school system.

“One of the promises of mayoral control is to leverage other city money as well as state and federal resources for this effort,” Bloomfield said.