The strange properties of the moon’s soil could be due to meteorites creating and smashing glass bubbles containing ultrafine particles on the lunar surface.

Working with researchers in Taiwan, Marek Zbik at Australia’s Queensland University of Technology (QUT) studied microscopic particles in soil collected from the moon’s surface during the Luna 16 robotic mission.

The lunar topsoil or regolith is very sticky and brittle, causing wear and tear to metal and glass. Most of its grains are like specks of dust at less than 10 micrometers in size.

“Lunar soil is electrostatically charged so it hovers above the surface; it is extremely chemically active; and it has low thermal conductivity, for example it can be 160 degrees [Celsius] above the surface but minus 40 degrees two meters below the surface,” Zbik explained in a statement.

“Clouds of lunar dust hover in low concentration usually [a] few centimeters above the ground,” he added via email. “However, particles were also found forming low density clouds as far as 100 km about the surface.”

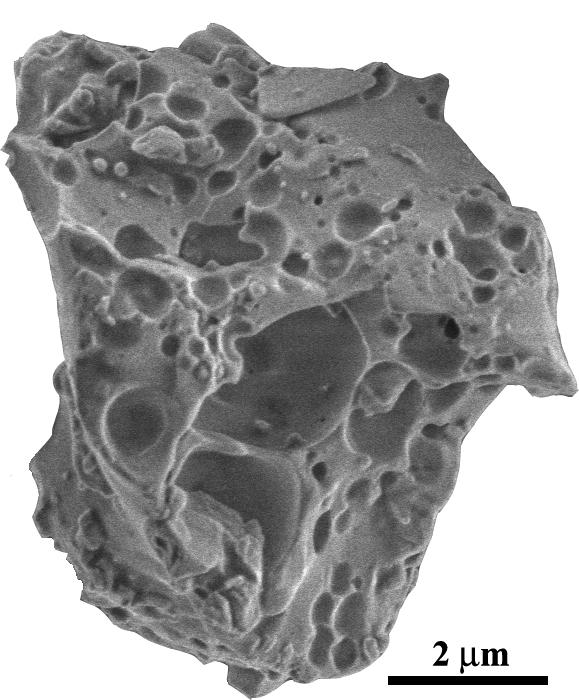

The scientists used a technique called synchrotron-based nanotomography to observe the bubbles’ 3D structure without breaking them.

[video]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=omRoS2SntMU[/video]

“Instead of gas or vapor inside the bubbles, which we would expect to find in such bubbles on Earth, the lunar glass bubbles were filled with a highly porous network of alien-looking glassy particles that span the bubbles’ interior,” Zbik said.

These nanoparticles seem to form inside molten rock bubbles when the moon is impacted by meteorites. They are released when subsequent strikes crush the resultant vesicles.

“This continuous pulverizing of rocks on the lunar surface and constant mixing develop a type of soil which is unknown on Earth,” Zbik said.

Nanoparticles follow the laws of quantum physics. When they are freed from the moon glass, they may mix with other materials in the soil to yield its unusual characteristics.

“Nanoparticles are so tiny, it is their size and not what they are made of that accounts for their exceptional properties,” Zbik explained.

As the moon has no atmosphere, there is no cushioning effect prior to meteorite strikes and the result is “very violent,” according to Zbik.

“Huge temperatures are generated which melts the rock,” he said. “The pressure goes and a vacuum is created.”

“Bubbles occur in the molten glass rock like soft drink bubbles trying to escape the bottle.”

The team aims to understand exactly how the nanoparticles form, which could have implications for new methods to develop nanomaterials.

The findings were published in the International Scholarly Research Network Astronomy and Astrophysics.

Read the research paper here.

The Epoch Times publishes in 35 countries and in 19 languages. Subscribe to our e-newsletter.