Commentary

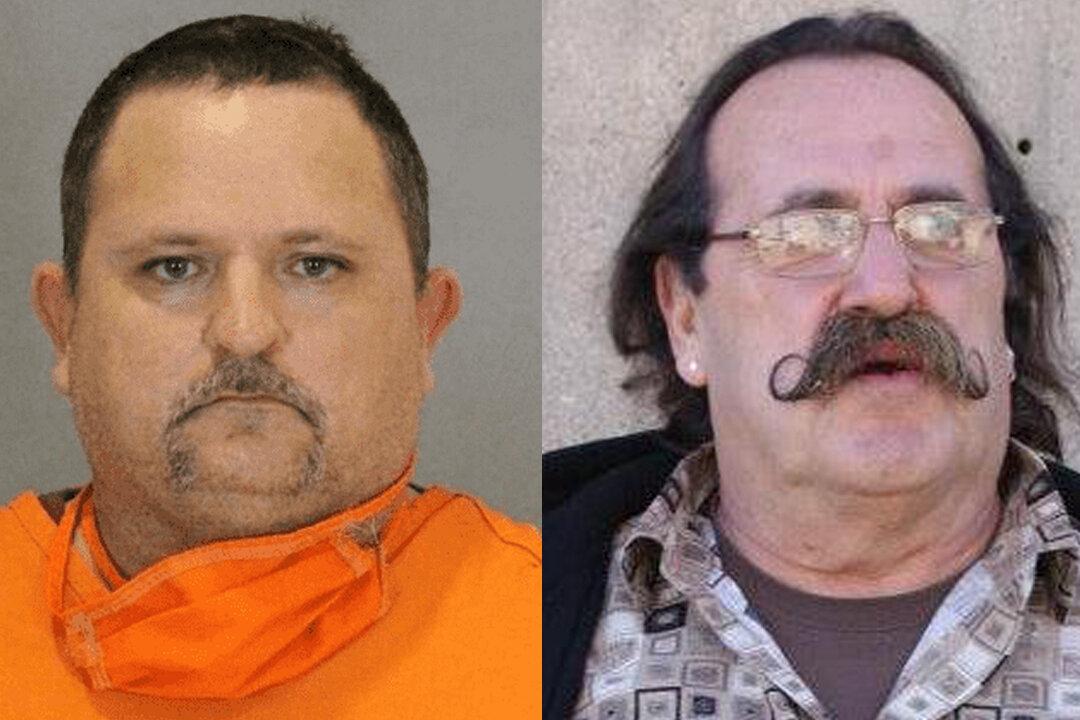

On the evening of May 14, 2020, in Omaha, Nebraska, James Fairbanks went to the home of Mattieo Condoluci and shot him dead. Condoluci, 64, was a twice convicted pedophile, and Fairbanks, 43, had spent years working with troubled kids in the Omaha Public School system.