SELLERSVILLE, Pa.—When I walked into the corporate office of Tohickon Glass Eyes, the company’s vice president, Tony Alfaro, was sitting behind a well-organized desk, wearing a shirt and tie. My first impression was that this was a small, well-run company in rural Pennsylvania that just so happened to make the world’s best eyes for taxidermy animals.

But soon I learned that the 40-year-old, family-run business nestled in Bucks County near the Delaware River has a history that could make for a Hollywood film, if a quirky one.

The word “tohickon” comes from the language of the local Lenape tribe, and some say it means “place of the deer.”

On a tour of the factory, Alfaro takes me to one of the production rooms, where he examines a tray of olive-brown deer eyes and discusses them with one of the factory employees. He later tells me that, true to the company’s name, the white-tailed deer is its bread and butter—the biggest seller, by far. Following that, the next four biggest sellers are bear, boar, bobcat, and fox.

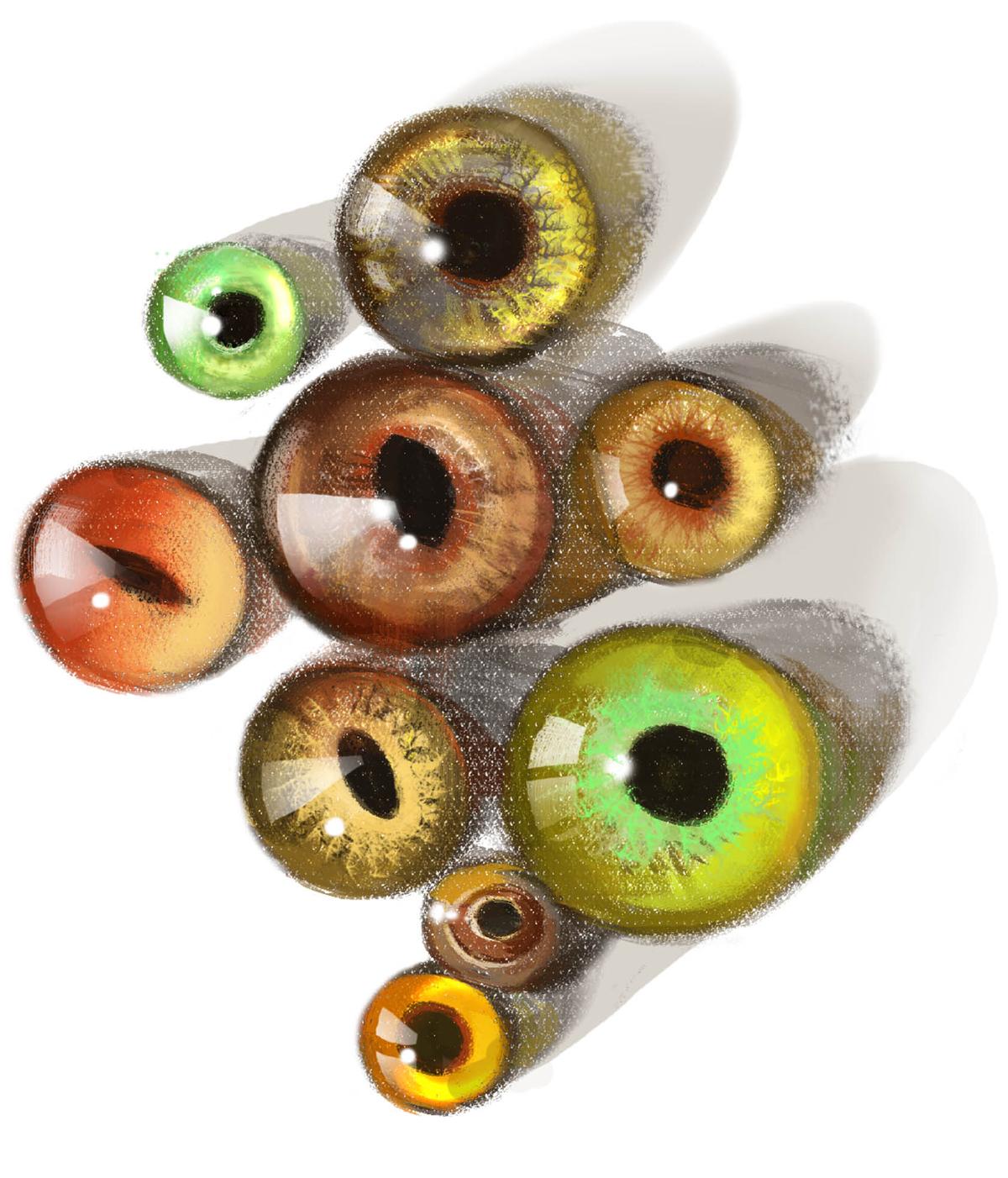

What they do here at Tohickon involves a vast and almost unimaginable network, connecting artists, hunters, animal lovers, museum curators, cryptozoologists, and more. The company makes perfectly replicated, hand-tinted glass eyes for your every animal reproduction or taxidermy desire: from large mammals, fish, and birds, to fantasy beings, dinosaurs, and even zombies (no pupils).

They sell half a million pairs of eyes per year, available in 20,000 variations.