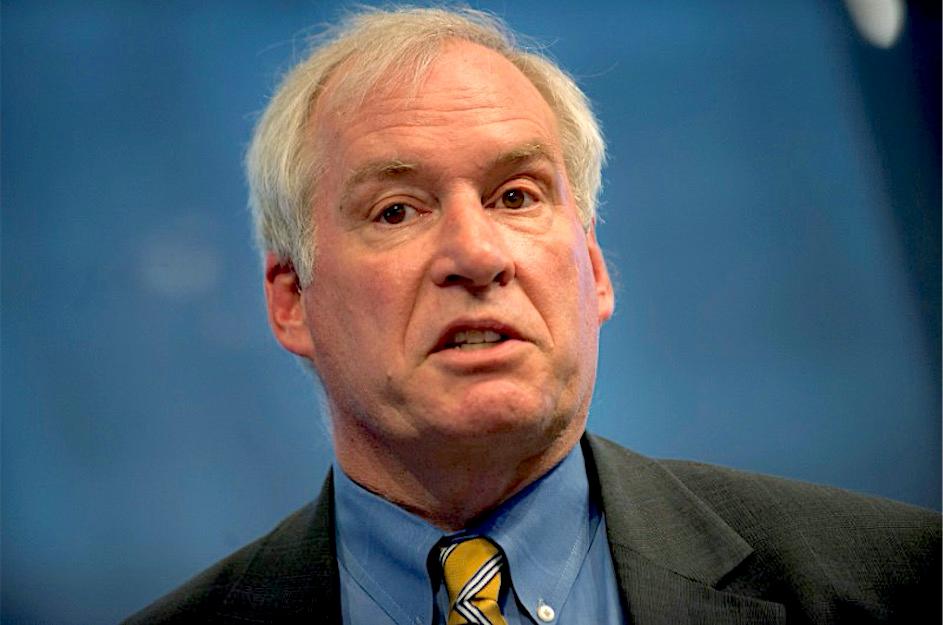

Eric Rosengren, president of the Boston Federal Reserve, said Wednesday that insufficient state-level measures to contain COVID-19 not only put lives at risk but are also likely to sap the strength of the economic rebound.

“Limited or inconsistent efforts by states to control the virus based on public health guidance are not only placing citizens at unnecessary risk of severe illness and possible death but are also likely to prolong the economic downturn,” Rosengren said in prepared remarks for delivery to the Massachusetts South Shore Chamber of Commerce.