GAINESVILLE, Fla.—After 24 years of teaching advanced math, Will Frazer calculated how the COVID-19 plan would affect students during the 2020-2021 school year and cringed.

Though Florida was one of the least-restrictive states in the country when it came to COVID-19 measures, he couldn’t compute how remote viewing of classes from home could further learning.

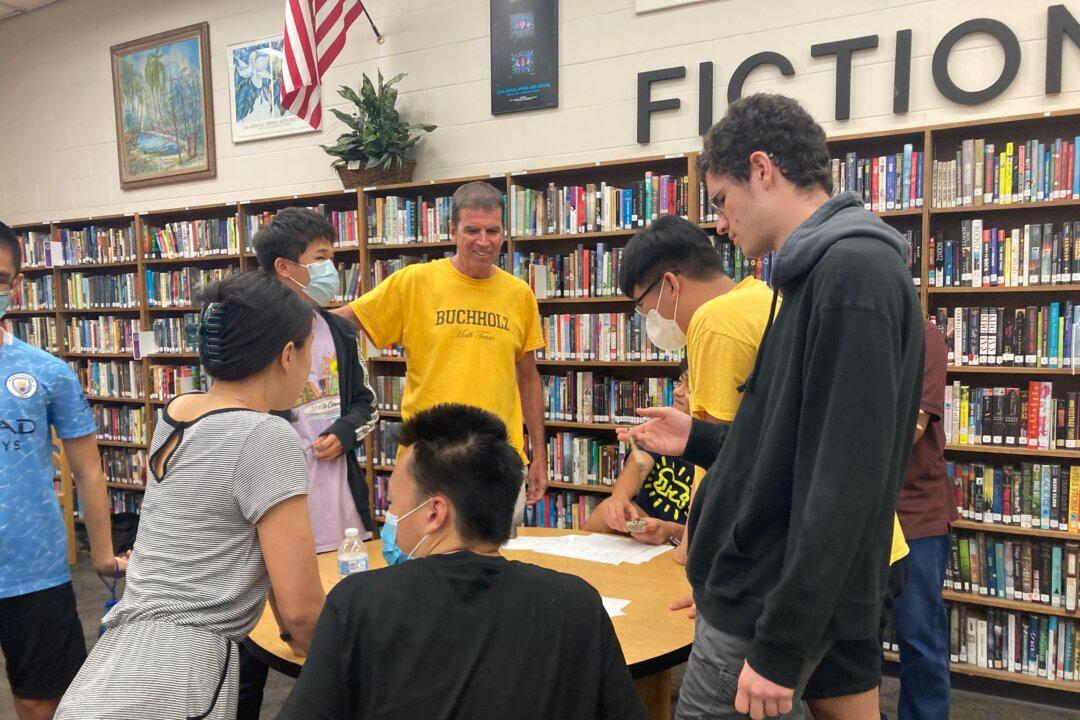

And he knew covering half his face with a mask certainly would impede his animated teaching style, even with those attending classes in person.

If the goal was to keep students on track in math, the plan didn’t add up, argued the Wall-Street-whiz-turned-public-school-teacher.

His students would fall behind, he knew in his heart. Already studies were emerging, documenting sickening trends teachers already recognized. Students kept out of classes because of the pandemic were experiencing learning losses, not gains.

Some students might not care, he knew.

But his did.