Editor’s note:

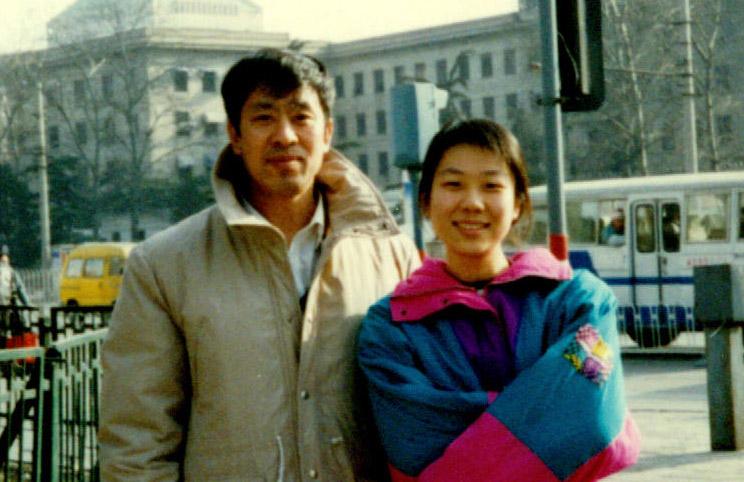

Wang Zhiwen is a practitioner of the spiritual discipline Falun Gong, and served as a coordinator for the practice in Beijing.

On July 20, 1999, Wang was arrested for his beliefs when former Chinese Communist Party leader Jiang Zemin ordered the persecution of Falun Gong. He was sentenced to 16 years in prison in a televised show trial in December 1999.

Two years after being released from jail, Wang secured travel documents to the United States, where he hopes to be reunited with his daughter. On Aug. 6, however, his passport was voided at customs.

Below is a personal statement by Wang Zhiwen, translated from Chinese.

My name is Wang Zhiwen. I would like to briefly describe my experiences after being released from prison.

Upon my release from jail on October 18, 2014, the Ministry of Public Security sent me straight to a “brainwashing center” (Xicheng District Legal Study Class) in Beijing’s Changping District. I only returned home on October 25.

My home environment was set up for surveillance: Four infrared security cameras were trained on my doorstep. I found out that a pump house opposite my apartment was used as a surveillance spot. The national security system arranged two shifts of agents to monitor me daily. Security agents were at all times aware of my comings and goings, and who I was in contact with. My neighbors are very clear on my situation.

Additionally, in the name of “maintaining social stability,” members of the local resident’s community and property staff were at times deployed to keep an eye on me.

Surveillance involved methods like wiretapping my telephone, and shadowing my person. The security details definitely make arrangements for periods that they consider sensitive. This type of surveillance has disrupted my personal life and artificially isolates me from the man in the street.

After being freed, I thought constantly of reuniting with my daughter. Due to special circumstances, I alone applied for my passport to realize a reunion in the United States. Police officers, however, read my mind.

In November 2014, the Xicheng District immigrations authorities rejected my application for a passport. Immigrations officials verbally told me that they wouldn’t process my application because I was under restrictions. I couldn’t find any such regulation online.

Over time, there was a change in my situation. In January 2016, I obtained a Chinese passport after submitting an application through official channels online. Then I began the process of arranging a reunion with my daughter, Wang Xiaodan, by applying for a U.S. visa.

During this process, the police interfered on several occasions:

(1) In February and March 2016, police officers Li Yajun and Wang Tongli from Xicheng’s Yuetan area paid me a visit at home, and demanded that I hand over my passport to them. They would return my passport should I need to use it, they said. I felt that this wasn’t necessary, and refused to surrender my passport.

In a subsequent telephone call, officer Li said his superior wanted to have a word with me at the police station. I knew my answer would reflect my stance on the matter of my passport, and told Li to tell his superiors that I saw no need to make a trip to the station. If they really wish to speak with me, I said, they can look me up at my home.

What I was indicating to officer Li is this: I had obtained my passport through official channels. While I wasn’t successful previously, my application has since been approved, and my passport is definitely legitimate.

(2) After I refused to surrender my passport on another occasion, police officers told me: “we’ve already cancelled your passport.”

(3) In July 2016, agents from the Ministry of Public Security increased their surveillance over me. From observing me at a distance, they shifted in close and never left my side. Day and night, I was being watched by two details of agents.

Everywhere I went—a trip to the market, a casual stroll, or even to the barber—I was closely followed by security agents. Some of these agents even walked up to me and asked, “Where have you been today?” Such was the degree of their familiarity with me.

(4) At around 10 a.m. on July 31, officer Liu, the deputy director of police in the Yutan area, led three of his subordinates from the Xicheng subdivision to my home. One of the policemen was officer Wang Tongli, and another went by the name Sun.

Liu said: You want to leave the country, but according to regulations, those whose rights are restricted aren’t allowed to travel. From today on, you have to submit an application to the police station if you wish to leave Beijing.

I told them that their surveillance over me was solely their own concern, and that I didn’t acknowledge their commands. After all, I had gotten my passport through formal channels, and if they had an issue with that, they should check with their superiors. I learned on the internet that there clearly isn’t any restriction on my person since my passport was obtained formally and legally.

If there were really any regulations, then the onus would be on the police to show me the relevant documents, I said.

Officer Liu replied that their communicating and clarifying the issue with me at my home was the furthest they could go to accommodate me.

During the conversation, I noted that their harassment—like taking photos of me the moment I speak with others—has severely disrupted my life. The police officers told me to bring this up with their superiors.

(5) On the evening of July 31, I eluded their surveillance (three agents remained on my tail though), and journeyed to Guangzhou to get my U.S. visa.

Agents from the public security system tracked me down again at a medical center in Guangdong, and they resumed surveillance after I obtained my U.S. visa from the Consulate General of the United States in Guangzhou.

Between 9 to 11 p.m. on August 5, officers from a local police station and over 20 others showed up on the doorstep of my rented room. My landlord even came over personally and demanded to be let in on the pretext that about a dozen people were engaging in “illegal activities” in my apartment. But at the stern insistence of my entourage, those at my door were turned away, and the situation didn’t escalate further.

(6) On the morning of August 6, I gathered up all my legally obtained documents, including my Chinese passport and U.S. visa, and tried to enter Hong Kong to catch a flight. At the ferry customs in Dongguang, an immigrations officer checked my passport, and asked: “Have you misplaced your passport? It says online that your passport has been cancelled.” Later, the officer said: “No reason was given for the cancellation of your passport; the cancellation was done by the internal bureaus of the Public Security Ministry.”

In the attempt to join my daughter in America, I had to go through a very long process of securing travel documents. I had to prepare various materials and spend some money. My family had also invested their hopes and expectations in my leaving China, while many others had also showed concern and support.

But now I’m left with this outcome due to the handiwork of some department in the Ministry of Public Security.

I’ve only briefly described my experiences. It’s really shocking that some in the public security system have appropriated the power of the state apparatus and used devious means to terminate a long-distance family reunion.

To reiterate, I wish to travel to the United States to reunite with my daughter. I applied for my passport in accordance with proper procedures, and I had legitimately obtained my passport.

What has befallen me is a real incident in Chinese society. I call upon everyone to take notice.

Wang Zhiwen

August 7, 2016