Commentary

The United States doesn’t appear to be particularly concerned regarding the global position of the U.S. dollar.

Amid a global secular shift away from the U.S. dollar (theoretical) and U.S. political influence (actual), the sentiment out of Washington is more akin to “What, me worry?”

Mainstream economists in the United States insist that the U.S. dollar is irreplaceable, and the global markets can’t replace the dollar as a medium of trade settlement. It’s certainly difficult, but not impossible.

We’ve previously discussed in this space that the West’s sanctions on Russian oil could spur the creation of a new global trade settlement regime backed by commodities and gold. But we underestimated the causation, because there’s more involved than just sanctions on Russia.

The dollar is a global currency because of the stability of the U.S. economy, the fairness of its political and judicial system, the strength of its financial markets, the creditworthiness of its central bank, and a massive supply of U.S. dollars from decades of running trade deficits in the second half of the 20th century.

But as the U.S. economy lurches from one near-crisis (regional banking failures) to potentially another (stagflation) and President Joe Biden’s political leadership continues to show a weak hand, other countries are beginning to make plans for a new global economic hegemony without Washington.

The economics and demographics are changing. The total combined population of Eurasia, South America, and Africa is almost four times that of North America, Western Europe, and Japan. The former bloc is rapidly industrializing. The BRICS nations— Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa—now make up the world’s largest gross domestic product contributor (31.5 percent), overtaking the G-7 nations (30.7 percent), according to UK-based Acorn Macro Consulting.

The share of the dollar as the global reserve currency is slowly declining. According to data from the International Monetary Fund, dollars were used in 58.4 percent of the trades as of the end of 2022, its lowest share since 1994. In 1978, dollars made up more than 85 percent of global trade settlements.

In late March, China and resource-rich Brazil reached a deal to settle trades in their own currencies, whereas previous trades were all settled in dollars. China has a similar currency deal with Russia and several other nations. Recently, China and France conducted a test trade in natural gas that settled in Chinese yuan. That has followed other currency movements: India and Malaysia, for example, recently began using the Indian rupee to settle trades. Oil exporter Saudi Arabia has spoken about the desire to diversify away from the dollar, though it hasn’t announced any plans yet.

“Many countries feel they can do transactions directly using their local currencies, which I think is good for the world to have a much more balanced use of currencies and payment systems,” Indonesian Finance Minister Sri Mulyani Indrawati told Bloomberg News at the sidelines of the G-20 meetings in December.These are small steps. And, ultimately, replacing one fiat currency with another (such as the yuan) doesn’t appear to be that feasible.

“The idea that the yuan can become a truly internationalized currency ... is a narrative that lacks substance,“ George Magnus, the former chief economist at UBS Investment Bank and current economist at Oxford University, wrote in a recent editorial. ”It could only happen if China allows the rest of the world to accumulate large claims in yuan.”

To make that feasible, China must run external deficits and permit free outward movement of capital to ensure a proper supply of available yuan, neither of which it would do. The other irony is that the yuan has a soft peg to the dollar to allow the regime in Beijing to adjust its currency to the benefit of its export economy.

The yuan, for all of China’s cheerleading, is only utilized in a little more than 2 percent of global trade.

Other methods are also problematic. Cryptocurrencies have their own issues. A newly created currency, backed by a basket of commodities, is potentially the most interesting alternative, but just as unlikely. Another alternative is the dollar joining several other global currencies in a basket to create a new “global trade exchange” currency.

Whatever the outcome, a reduced usage of the dollar would result in higher interest costs and lower global demand for U.S. Treasurys. Over a long enough time period, that would mean reduced U.S. government spending, higher taxes, and higher inflation. A less-effective U.S. dollar also blunts America’s ability to sanction and impose economic hardship on enemy nations.

Wall Street appears to be preparing for a near-term shift.

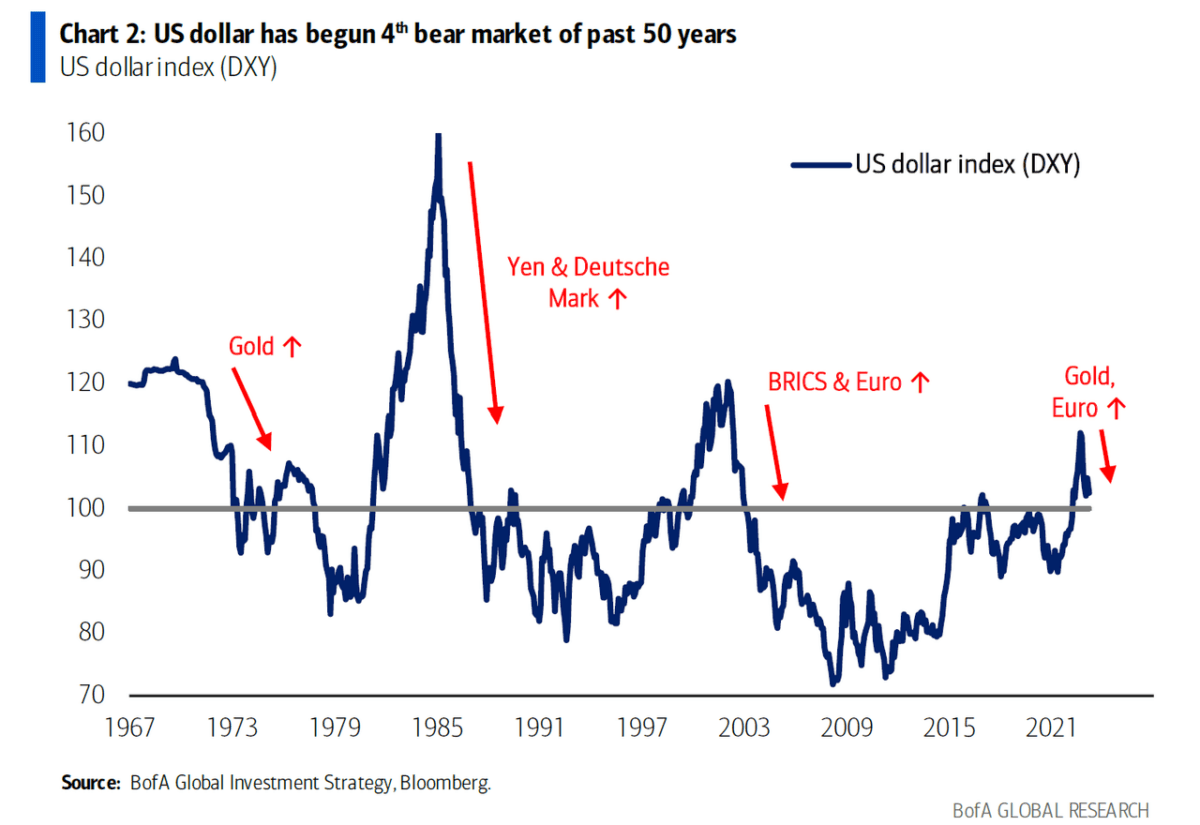

Michael Hartnett, Bank of America’s chief investment strategist, for example, wrote in a recent note to clients that “U.S. dollar debasement” is now a “new favorite theme.” He recounts the dollar’s double-digit decline since last September, in conjunction with gold spot price above $2,000 per ounce and bitcoin’s rise to above $30,000 as signs that the U.S. dollar will soon enter its “fourth bear market of the past 50 years.”

UBS in late March recommended that its clients add gold, a basket of emerging markets currencies, and the Australian dollar as a hedge against potential U.S. dollar decline.

While it is unlikely to pass, another positive development for gold is the recently Republican-introduced congressional “Gold Standard Bill” to re-peg the Federal Reserve note to gold bullion.