Is there something intrinsic in the Irish persona that doomed the Celtic Tiger to have a hard crash rather than a soft landing, or is it the chancer inherent in the Irish disposition that ran out of luck?

We, (the Irish), have a number of affectionate phrases to describe a person who is liberal with the truth, one of which being ‘a chancer’. Meaning a person who would take a risk to make a gain. We also have a few affectionate phrases to describe such a person, such as “sure isn’t he a grand fella”, “fair play to him”, “sure wouldn’t you do the same yourself.” All praising an individual for making a gain in a ‘cute’ way.

People make their own luck by either deceit or hard work. However for the Irish there is the grey area between the two where hard work and a little deceit is deemed ‘fair play’.

I was listening to RTE Radio One last summer and there was a discussion about Conrad Black that struck me. A panel of Irish punters were discussing the fall of this ’millionaire who lived like a billionaire,‘ a guy who according to his biographer Tom Bower flaunted his wealth. Initially the conversation focused on his faults and that he was brought to justice, however after a few minutes discussion Irish members of the panel were calling him a ’grand fella' and seemed to be patting him on the back for living the high life at the expense of others. It was only when a British guest joined the panel he sternly reminded them that the money Mr Black took more than likely came from pension funds and that no, actually he was not a grand fella. There was audible anger in the British contributors voice and it rattled the Irish contributors and host who seemed for a minute at least lost for words.

For the Irish public the phrase ‘chancer’ combined with thoughts of high office in Ireland bring memories of decades of question marks hanging over generations of political leaders. Of course, the majority of Irish politicians are hard working, honest and ethical but for the purpose of this piece we are discussing the chancers, or the cute fellas who bent the rules. Every country has its share of people who are dishonest but perhaps for us the acceptability of dishonesty is on a scale and is not merely a black and white issue. To the Irish some dishonesty seems acceptable and some even commendable.

The definition of a ‘chancer’ as defined by the Irish travel guide is:“A ‘chancer’ is a mildly unscrupulous person who tries to get away with things when the opportunity presents itself.” Such a definition is integrated into our popular culture and our way of doing things and even how we look out for each other. An advert on radio has the TV licence man coming around to collect the fee. In one hose a student answers the door and says he doesn’t have a television, but then gets tricked into admitting that he does; a pensioner tries to argue that it’s a recession and tries to pay with a cake. In the Irish persona this isn’t deceit that is frowned upon but instead a bit of ‘craic’ (Irish for fun) that is often praised or bragged about if successfully carried off.

Even in something as serious as road traffic safety this intrinsic dishonesty is present. If an Irish punter comes across a police speed check and further down the road sees a fellow motorist speeding he will flash his lights to warn of the imminent danger of getting caught. And it’s not just the ordinary punters, even respected social leaders bend the truth as if it is a loose commodity; the spokesperson for the Road Traffic Authority was promoting an event in a neighbouring county to Dublin, after describing this fantastic event he said it was only thirty minutes from Dublin. However it is highly questionable whether it was thirty minutes from Dublin when adhering to the rules of the road. Personally I think he was chancing his arm!

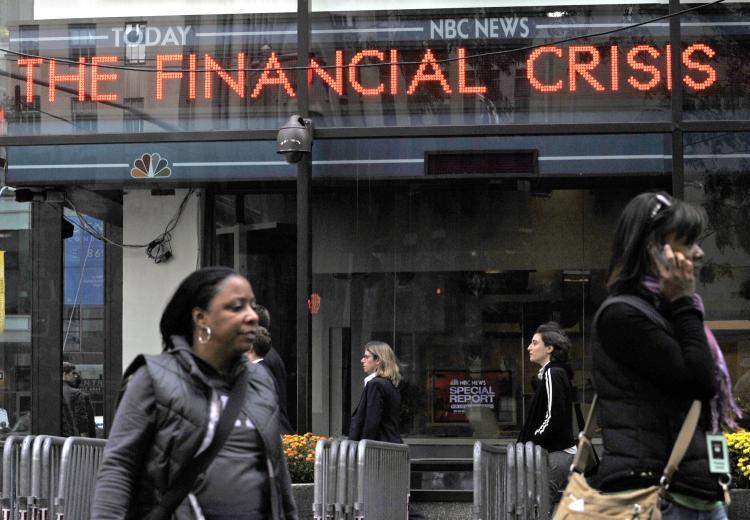

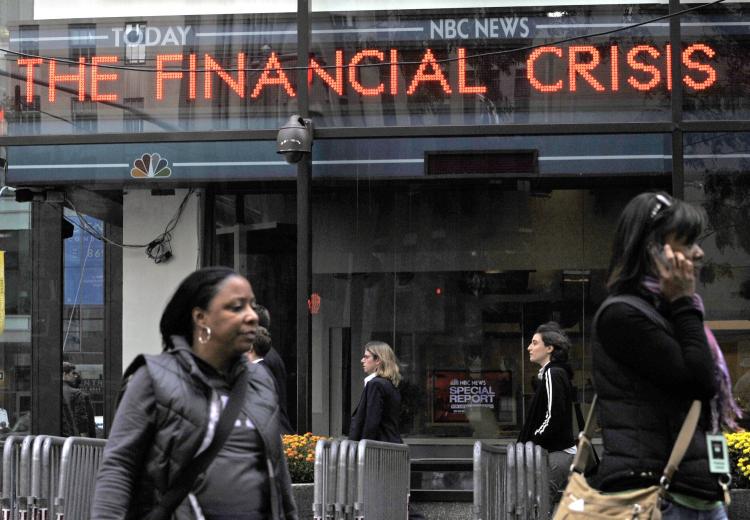

Then there is the recent financial disaster. Our financial system was labelled by some in Europe as the wild west of Europe. Why? Possibly because some of the people operating it are chancers. There are stories of leading bankers lending themselves 87 million, mortgages being lent on flimsy deposits, auditors who didn’t seem to notice vast sums swashing around. These bankers were quick to tell us that they had not broken any laws, that they had only bent the rules and chanced their arms. Sure, you would do the same in our position they seemed to imply. The ultimate chancers are the builders or developers who are trying to renege on their bank loans arguing that the banks were at fault for giving them the money in the first place!

So where does this come from and where is it going? When did a mild form of dishonesty become acceptable? It is possible perhaps that this now mature character trait had roots in colonial times. If a citizen thinks that they are paying taxes to a government which they feel does not represent them, or at worst is persecuting them, then of course getting out of paying ones taxes could be accepted as a good thing. However, Ireland has long left its colonial past. Thanks to the leadership of Bertie Ahern, Tony Blair and others, Britain and Ireland enjoy a positive relationship. Now some chancers are running the banks, are members of government, and big business, and when they are being ‘cute’ as we have seen in our recent history, it is Irish public and Irish pension funds, ect that suffer. Perhaps its time we hold the chancers to account.

We, (the Irish), have a number of affectionate phrases to describe a person who is liberal with the truth, one of which being ‘a chancer’. Meaning a person who would take a risk to make a gain. We also have a few affectionate phrases to describe such a person, such as “sure isn’t he a grand fella”, “fair play to him”, “sure wouldn’t you do the same yourself.” All praising an individual for making a gain in a ‘cute’ way.

People make their own luck by either deceit or hard work. However for the Irish there is the grey area between the two where hard work and a little deceit is deemed ‘fair play’.

I was listening to RTE Radio One last summer and there was a discussion about Conrad Black that struck me. A panel of Irish punters were discussing the fall of this ’millionaire who lived like a billionaire,‘ a guy who according to his biographer Tom Bower flaunted his wealth. Initially the conversation focused on his faults and that he was brought to justice, however after a few minutes discussion Irish members of the panel were calling him a ’grand fella' and seemed to be patting him on the back for living the high life at the expense of others. It was only when a British guest joined the panel he sternly reminded them that the money Mr Black took more than likely came from pension funds and that no, actually he was not a grand fella. There was audible anger in the British contributors voice and it rattled the Irish contributors and host who seemed for a minute at least lost for words.

For the Irish public the phrase ‘chancer’ combined with thoughts of high office in Ireland bring memories of decades of question marks hanging over generations of political leaders. Of course, the majority of Irish politicians are hard working, honest and ethical but for the purpose of this piece we are discussing the chancers, or the cute fellas who bent the rules. Every country has its share of people who are dishonest but perhaps for us the acceptability of dishonesty is on a scale and is not merely a black and white issue. To the Irish some dishonesty seems acceptable and some even commendable.

The definition of a ‘chancer’ as defined by the Irish travel guide is:“A ‘chancer’ is a mildly unscrupulous person who tries to get away with things when the opportunity presents itself.” Such a definition is integrated into our popular culture and our way of doing things and even how we look out for each other. An advert on radio has the TV licence man coming around to collect the fee. In one hose a student answers the door and says he doesn’t have a television, but then gets tricked into admitting that he does; a pensioner tries to argue that it’s a recession and tries to pay with a cake. In the Irish persona this isn’t deceit that is frowned upon but instead a bit of ‘craic’ (Irish for fun) that is often praised or bragged about if successfully carried off.

Even in something as serious as road traffic safety this intrinsic dishonesty is present. If an Irish punter comes across a police speed check and further down the road sees a fellow motorist speeding he will flash his lights to warn of the imminent danger of getting caught. And it’s not just the ordinary punters, even respected social leaders bend the truth as if it is a loose commodity; the spokesperson for the Road Traffic Authority was promoting an event in a neighbouring county to Dublin, after describing this fantastic event he said it was only thirty minutes from Dublin. However it is highly questionable whether it was thirty minutes from Dublin when adhering to the rules of the road. Personally I think he was chancing his arm!

Then there is the recent financial disaster. Our financial system was labelled by some in Europe as the wild west of Europe. Why? Possibly because some of the people operating it are chancers. There are stories of leading bankers lending themselves 87 million, mortgages being lent on flimsy deposits, auditors who didn’t seem to notice vast sums swashing around. These bankers were quick to tell us that they had not broken any laws, that they had only bent the rules and chanced their arms. Sure, you would do the same in our position they seemed to imply. The ultimate chancers are the builders or developers who are trying to renege on their bank loans arguing that the banks were at fault for giving them the money in the first place!

So where does this come from and where is it going? When did a mild form of dishonesty become acceptable? It is possible perhaps that this now mature character trait had roots in colonial times. If a citizen thinks that they are paying taxes to a government which they feel does not represent them, or at worst is persecuting them, then of course getting out of paying ones taxes could be accepted as a good thing. However, Ireland has long left its colonial past. Thanks to the leadership of Bertie Ahern, Tony Blair and others, Britain and Ireland enjoy a positive relationship. Now some chancers are running the banks, are members of government, and big business, and when they are being ‘cute’ as we have seen in our recent history, it is Irish public and Irish pension funds, ect that suffer. Perhaps its time we hold the chancers to account.