NEW YORK—For more than a year, Jason Xiong was tied to a bed in a small prison cell and force-fed through a tube inserted into his nose going into his stomach.

All four of his limbs were outstretched, lashed with ropes to the edges of a wooden bed frame.

Every few days or so, prison inmates would funnel some liquid sustenance, such as soy milk, milk, or congee, down the tube.

“It was very painful,” he told The Epoch Times. “But I gritted my teeth and persevered.”

Xiong was imprisoned in China for doing nothing more than practicing his faith. In an act of defiance, he started a hunger strike to protest the senseless persecution. The unwavering torture he suffered, however, brought him to the brink of death.

More than a decade later, Xiong, now safe and living in New York City, recalls his experiences of being tortured, harassed, and detained for his beliefs as though it were a dream.

“It was a very difficult time,” he said. “[I] had to overcome many challenges, some of which are hard for the average person to imagine.”

Xiong, originally from Shanghai, practices the spiritual discipline Falun Dafa, also known as Falun Gong. The traditional Chinese practice consists of meditation exercises and a set of moral teachings based on the principles of truthfulness, compassion, and tolerance.

Following its introduction to the public in 1992, Falun Gong surged in popularity in China, with around 70 million to 100 million adherents by the end of the decade, according to government estimates cited by Western media at the time.

The Chinese communist regime, feeling threatened by this popularity, banned the practice in 1999 and began a nationwide persecution of adherents. Practitioners were rounded up and sent to labor camps, prisons, brainwashing centers, and other detention facilities in an effort to force them to renounce their faith.

Beginnings

Xiong started learning Falun Gong in 1997 at the age of 25, after seeing the effect of the practice on his grandfather.His grandfather had a heart ailment that doctors said couldn’t be treated. But after practicing the Falun Gong exercises, his health dramatically improved. Xiong was shocked to find his previously ill grandfather in good health and spirits, and asked him what caused this turnaround. His grandfather handed Xiong the book, “Zhuan Falun,” the main text of Falun Gong, and Xiong started reading.

The biggest change that Xiong experienced was in his outlook on life. He learned how to be a good person and to improve his moral character by applying truthfulness, compassion, and tolerance in his daily life.

“This gave me a direction in life,” Xiong said.

He also noticed a dramatic improvement in his physical health. Previously, Xiong would often get sick and run fevers, and his body felt weak.

“After practicing Falun Gong, I distinctly felt my body getting stronger,” he said. “The illnesses also disappeared.”

In late 1998, Xiong, who worked as a civil servant in the Shanghai government, was recognized at his workplace as an “outstanding” employee.

“In my heart, I knew that all these changes came from my practicing Falun Gong,” he said.

Suppression

Everything changed in July 1999.On July 22, 1999, Xiong was at work when everyone in his office was instructed to go to a meeting room and watch a television broadcast on China’s state-run CCTV. The broadcast said the authorities had branded Falun Gong as a “heretical religion” and ordered practitioners to give up the practice.

He didn’t even know what to think. Until then, he was just an ordinary citizen.

“I was trying to be a good person,” he said. “I carried out my duties and observed the law.”

Suddenly, the authorities accused him of being someone he wasn’t, Xiong said. The consequences would be serious.

“From that day onwards, [my] life—everything—turned upside down,” he said.

Each day at work, Xiong was sent to an office to meet with two people. Sometimes, they were his superiors; often, they were people he didn’t know. All would use a combination of inducements, guile, and threats to coerce him to give up the practice of Falun Gong.

Meanwhile, he was forced to watch and read the propaganda that had begun to blanket the airwaves and print media.

Xiong’s supervisors no longer assigned work to him—his only job now was to bend to the will of the state.

He refused to give in. He decided to write a statement about his personal experience of practicing Falun Gong, and distributed it to his superiors and to various departments at his workplace.

And he wanted to do more: He wanted to tell the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to stop targeting ordinary citizens who were only seeking to live peaceful lives and improve their character.

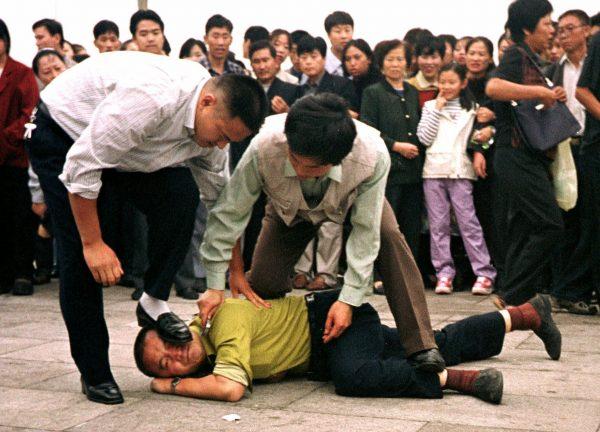

Like many practitioners at the time, Xiong went to the capital to petition the authorities to end the persecution. He traveled to Beijing in late December 1999 and went to Tiananmen Square to practice Falun Gong exercises as a form of protest.

At the square, uniformed and plain-clothes police were everywhere, while police cars were lined up around the precinct. They were ready for him and the scores of practitioners from all over the country who spilled into the square daily to appeal the persecution.

“I felt my body was very heavy,” he said. “I felt as though every step I took encountered resistance.”

Nonetheless, Xiong entered the square and began doing the first standing exercise, with his arms stretching and relaxing in different positions. Almost immediately, he was manhandled by nearby police and forced inside a van.

A young policeman repeatedly struck Xiong in the face with the handle of a knife, while another officer slapped his face and kicked him in the stomach. After he was beaten for half an hour, his face was swollen beyond recognition.

Labor Camp

One night after his release in February 2000, Xiong was at home having dinner with his parents, when police came knocking. They asked him to go to the police station for a talk. The unsuspecting Xiong agreed, although his mother sensed that something was amiss.But by then, it was too late. From the police car, Xiong saw his mother rush out of the building and stand helplessly on the side of the road as he was taken away. This image still haunts him to this day.

At the station, authorities sentenced Xiong to a year and a half in a labor camp for distributing the personal statement at his workplace and for going to Tiananmen Square to do the exercises.

He was first confined at a detention center in Putuo district in Shanghai. He felt so depressed he couldn’t eat, and after a while, this natural abstention morphed into a willful act of resistance.

“I was locked up in here, so what method could I use to protest?” he said.

During the hunger strike, about every three days, the guards would order other inmates to pin Xiong down while a doctor snaked a long rubber tube into his nose and down to his stomach. The guards then funneled soy milk into the tube.

That lasted for about 30 days, until the authorities, thinking he might die, transferred Xiong to a local hospital for treatment.

While Xiong was under constant guard, his mother was allowed to visit him and help him start eating again. After a few weeks, Xiong slowly began to recover. Fearful that he would be sent back to detention after recovery, he managed to escape while the guard was distracted.

Xiong fled to Beijing and stayed at the home of a friend who also was a Falun Gong practitioner. But after about two months, the friend, his wife, and Xiong were arrested by Beijing police. Xiong was returned to Shanghai and sentenced to an additional year in a labor camp, bringing his total sentence to 2 ½ years.

In June 2000, Xiong was sent to Shanghai No. 1 Forced Labor Camp in Yancheng City, Jiangsu Province. While inside, Xiong shared a room with three criminals who were tasked with monitoring and abusing him. Every day, they forced him to sit on a tiny stool with his legs together, back straight, hands on his knees, and eyes staring straight ahead. If Xiong slackened from that position, the inmates would hit or shout at him.

He sat that way from 6 a.m. to 10 p.m. every day, only allowed breaks for meals and to use the restroom. Soon, the skin on his buttocks began wearing away, causing him intense pain.

Xiong again went on hunger strike. This time, the guards ordered the criminals to tie each of his four limbs to a wooden bed frame, so that his body resembled the shape of a star. His torso was also secured by rope to the frame. Again, he was force-fed through a foot-long plastic tube that was inserted into his nose.

The three criminals watched over him around the clock. Out of boredom, they would hit Xiong’s face, torso, and legs with a bamboo stick; they laughed as they jabbed his armpits, ribcage, and abdomen.

Xiong managed to persevere for four months.

“I knew that I couldn’t back down,” he said. “If you back down at the hardest part, then you’ll collapse. It’s all over.”

The prolonged torture seriously damaged Xiong’s stomach, shoulders, and other joints, as well as the nerves in his feet. Fearing Xiong might not pull through, authorities again transferred him to a hospital, where it was found that he had severe gastritis and bleeding in his stomach. He was unable to lift anything, and his right foot was practically immobile.

Because of his dire health condition, officials at the labor camp—fearing that they would be held responsible should he die from torture—released him in October 2000. When he returned home, Xiong continued practicing the Falun Gong exercises and studying the teachings. Within a few months, his health was completely restored.

As Xiong was recuperating at home, he began printing posters and other materials with information about Falun Gong and the ongoing persecution, seeking to dispel the Chinese regime’s propaganda. These materials were handed to other practitioners around Shanghai, who then distributed them. Later, as his health improved, Xiong began distributing the materials himself.

Xiong was arrested again with two other practitioners in May 2001, after being tailed by several plain-clothes policemen. This time, he was sentenced by a court to four and half years at the Tilanqiao Prison in Shanghai.

The guards there were instructed by the local “610 Office”—a Gestapo-like extrajudicial organization tasked to persecute Falun Gong practitioners—to “transform” practitioners, by any means possible.

Three inmates were assigned to monitor Xiong and get him to “transform”—that is, to renounce his beliefs. He was beaten and forced to sit on a tiny stool for long periods of time and watch material slandering Falun Gong.

Xiong started another hunger strike, on and off for two years. He was tied to a wooden bed in his cell for about a year from 2004 to early 2005. The dirty ropes used to tie his wrists and ankles caused him to develop rashes that oozed pus and were extremely itchy.

Unsuccessful at breaking him, prison authorities escalated their efforts to “transform” Xiong by transferring him to the part of the prison that housed the most violent criminals. A group of roughly six criminals, later increased to 10, were tasked with supervising Xiong in rotation. The group was told that their sentences would be reduced if they could force Xiong to renounce his faith.

Several inmates would repeatedly smash Xiong into the wall or the ground. They used a wooden stick to hit the bare soles of his feet, only stopping when the stick broke from the force of the beating. They shoved the dirty bristles of a bamboo broom into his face, causing him to bleed in several places, and leaving scars that are still visible today.

In March 2005, an inmate used the hard plastic heel of a slipper to repeatedly hit Xiong in the head. The wounds began to bleed, and his head became so swollen that it looked as though he was wearing a helmet. When Xiong was taken to the hospital, the prison guards covered up the torture by claiming that he was injured in a fall.

It took months for the swelling and scabs on Xiong’s head to heal. To this day, there’s a patch on his head where he can’t grow hair.

The inmates kept up their attacks. Every few minutes, 24 hours a day, they would hit him, or if they were too lazy to expend the effort, they would put chilli powder, cologne, or mosquito repellent oil onto his mouth, nose, and eyes. They told Xiong that they were there to make him wish he were dead.

They almost succeeded. Because of the unrelenting torment, Xiong worried that he may have reached the limits of his endurance, yet there was still some fight in him, which he partly attributes this to his stubborn personality.

“When you know you are right, then there’s nothing to be afraid of,” he said.

“I didn’t want to die. But if you try to force me to kneel before you and become your slave, then I won’t do it.”

One day, Xiong overheard other inmates talking about tactics to get transferred out of detention. One of the ways was to ingest a pen. So, in a last-ditch show of defiance, Xiong furtively took two pens while the inmates weren’t looking and swallowed both of them.

One of the pens passed through, but the other ended up lodged between his intestines and liver, prompting another trip to the hospital. There, the doctors found his body gravely damaged from the torture: He had a lung infection, was running a high fever, and had dangerously low blood pressure. Thinking he was going to die, the prison released Xiong in April 2005 to his mother, who found a hospital where doctors were able to remove the pen.

When Xiong was discharged, his body was severely weakened and riddled with injuries.

Xiong largely recovered within six months, but even still, the prolonged torture left permanent scars. To this day, he often has pain in his back, abdomen, and knees, and experiences numbness in his right leg.

In the years that followed, Xiong managed to find a job working in human resources at a manufacturing company, and tried to live a normal life.

But it wasn’t normal at all. After his release, Xiong was still under constant surveillance by police, and was followed everywhere he went. Even so, Xiong learned to evade the police, and snuck off to distribute materials and meet with other practitioners; he did that for eight years.

But that took its toll on Xiong’s family members, who lived in constant fear of the moment when police would come knocking at the door.

So in 2013, Xiong decided to move to the United States. His family, whose only wish was for Xiong to be safe, were happy with his decision.

Freedom

After almost 14 years of persecution, living in an environment saturated in fear and brutality, Xiong’s heart had hardened. But when he arrived in New York City, he instantly felt a sense of relief.“It was like a burden was lifted from my heart,” he said. “[I realized that] this is what [life] is supposed to be like.”

Xiong said he never cried during his years of suffering in China. But seeing practitioners from around the world participate in parades and carry banners calling on the Chinese regime to end the suppression has often moved him to tears.

“To see these scenes, after so many years in China, it was like a spark, bringing up all these emotions,” he said.

These days, Xiong goes to major tourist attractions in New York City to tell people—often visiting tourists from mainland China—about his experiences, the Chinese regime’s propaganda, and the ongoing persecution.

This is the least he can do, Xiong said, given that so many of his fellow practitioners are still suffering in his homeland.

As long as the persecution persists, Xiong won’t be able to return to China to see his family.

“I wish that one day I can go back and be reunited with them,” he said. “I believe we will see that day.”