The vicious Ebola virus outbreak that has already killed more than 800 people this year, in addition to sowing panic, fear and confusion throughout West Africa, was not a strain endemic to the region as initially believed. Instead the University of Edinburgh found that the strain is the same as the Ebola Zaïre found in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), formerly Zaïre. The Robert-Koch Institute in Germany confirmed the finding.

In fact, this is the first outbreak of Ebola Zaïre seen anywhere in West Africa, and it is already the most severe in recorded history, both in number of cases and fatalities. The fatality rate varies from 50 to 90 percent of those infected, and there is no cure or vaccine—it is one of the most deadly diseases on the planet. Victims bleed to death and organs fail as they hemorrhage internally and from every orifice.

No wonder Kamono Moriba, a volunteer with the Red Cross Society of Guinea who lives in Guéckédou, where the first cases of this epidemic were reported, said “I was so scared to die.”

“People tell us that the humanitarian workers have brought the disease…They also say that for several decades they have consumed bushmeat without contracting any disease, and question why it is surfacing now,” relates Moriba.

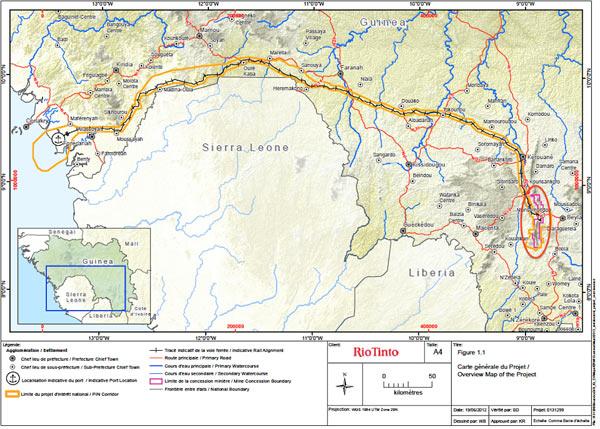

The original explanation for the virus breaking out in this remote part of southeastern Guinea, near the borders of Sierra Leone and Liberia, was that people had eaten infected bushmeat. Fruit bats are thought to be the natural reservoir of all strains of Ebola virus, and they can pass it on to other species in various ways, including through their feces, dropping pieces of half-eaten fruit that other animals eat, or by being butchered and eaten themselves as bushmeat.

Bats are a popular food in West Africa. I remember seeing their flayed, smoked carcasses looking like macabre crucifixions on wooden crosses sold in railway stations and by the roadside when I was a Peace Corps Volunteer in Côte d'Ivoire many years ago.

I could imagine being infected in a way similar to that shown in the movie Contagion. A bulldozer clears an area of forest in Africa for a new piggery. Then an infected bat drops a piece of nibbled banana, which is scoffed by a pig that later ends up in a restaurant kitchen. The cook, who doesn’t wash his hands, infects Gwyneth Paltrow’s character, setting off a terrifying scenario, similar to that unfolding now in West Africa.

But Moriba’s question remains apt. Why is it breaking out now almost 40 years after the first recognized Ebola epidemic appeared in 1976 in the DRC?

A detailed genetic study of the virus in Guinea published in May in PLOS Currents concluded that “the outbreak in Guinea is likely caused by a Zaïre ebolavirus lineage that has spread from Central Africa into Guinea and West Africa in recent decades, and does not represent the emergence of a divergent and endemic virus.”

A second report published in June also supports this view, determining that it was “extremely unlikely that this virus falls outside the genetic diversity of the Zaïre lineage.” Their analysis “unambiguously supports Guinea 2014 EBOV as a member of the Zaïre lineage”.

The fact that we’re dealing with a strain of the virus never seen in West Africa before shoots down the bat theory of origin, unless someone can demonstrate a diseased fruit bat flew over 2,000 miles from the DRC to Guinea, and perhaps dropped a chewed banana into a piggery.

But, there are better candidates for the epidemic’s origin. Recently, gorillas and bonobos may have been stolen from the wild in the DRC and transported by wildlife traffickers to Guinea’s capital, Conakry. Five previous outbreaks of Ebola in Central Africa have been linked to the handling of meat from gorillas, chimps and duikers (a small antelope) for the bushmeat business. As known carriers of the Ebola virus, these great apes—and their human captors—could have brought the disease with them.

In fact, The CITES Trade Database shows that ten gorillas were exported from Guinea to China in 2010. But Guinea has no indigenous gorillas, nor does it have any breeding facilities for it. Karl Ammann, a wildlife trafficking investigator and photo-journalist, believes these ten gorillas originated in the DRC. Meanwhile, the former head of the DRC CITES Management Authority, Leonard Muamba-Kanda, stated on video camera that he knew the route that the gorillas took from the DRC to Guinea, before shipment to China.

With the assistance of an NGO working in China, four of the gorillas were tracked down to the Changsa Zoo. Ammann visited the zoo in January 2014. A zoo keeper told him through an interpreter that the female keeper who was in charge of the gorillas when they first arrived became sick and was diagnosed with hepatitis. She was returned to her home in northern China. The gorillas were then tested for hepatitis, two were found positive and all four were then euthanized. But could the disease in reality have been Ebola? Not all Ebola cases show hemorrhaging. More investigation is needed to ascertain how the disease was diagnosed and what happened to the infected keeper.

But it might not just be gorillas. In 2011, a CITES Secretariat mission in Guinea investigating unusual great ape trade activity found two export permits for bonobos to Armenia. Bonobos are indigenous to one country: the DRC. The CITES Secretariat did not follow up on it, but Ammann did. Working with Armenian investigative journalist Kristine Aghalaryan, they tracked down one of the bonobos to a private safari park called Jambo Park, located in Dzoragbyur. The other bonobo had died. The cause of the death was not stated. The bonobo’s range overlaps with previous outbreaks of Ebola Zaïre.

Through interviews and obtaining a list of animals imported to Armenia from the State Revenue Committee, Aghalaryan established that at least five bonobos and seven chimpanzees were imported to the European country in 2011 and 2012. None of these are reported in the CITES Trade Database. Could they all have gone from the DRC to Guinea before being trafficked to Armenia?

A number of great ape traffickers are also known to be based in Guinea, many of whom have family relations with wildlife traffickers in the DRC. These Guinean traders travel back and forth between Guinea and the DRC on a regular basis while arranging their mostly illegal wildlife trade deals. One of them could have become infected with Ebola and brought it back with him to Guinea.

“The ape dealers in Conakry have collection teams that go into the forest, kill chimp mothers and capture the infants,” Ammann told mongabay.com. “They bring them to Conakry. The dealers are the same guys with family connections in Kinshasa [in the DRC].”

The elements are there to propose the following hypothesized scenario. Wildlife traffickers capture gorillas and/or bonobos (possibly even chimpanzees) in the DRC. They go to Guinea en route to another destination such as China or Armenia, but an ape or trafficker infected with Ebola Zaïre brings the virus along. Then the infected trafficker goes on a collecting trip for chimpanzees in the Guéckédou area and infects a person there. According to officials, the virus has been first speculatively traced to a two-year-old child in December 2013 in a village near Guéckédou. The contagion spreads from there.

The fact that the Ebola did not break out in Conakry or elsewhere first cannot be explained at present, but working out the entire history and epidemiology of this outbreak is of highest priority in order to prevent a repeat occurrence. Great ape trafficking could have much more serious consequences than ever imagined.

The chimpanzees living in Guinea are also at risk, since great apes have suffered even more from previous Ebola epidemics than humans. Up to 90 percent of local great ape populations have been wiped out by Ebola during past outbreaks in Central Africa, particularly in areas of deforestation, which characterizes much of West African ape habitat.

A half-eaten banana dropped by an infected human and found by a chimpanzee could spell doom for the already threatened western chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes verus).

This article was originally written and published By Daniel Stiles, a special reporter for news.mongabay.com. For the original story and more information, please click HERE.