For some, it would be their worst nightmare to be sent to the Middle East to join anti-ISIS fighters on the ground. For others, it’s a dream come true. Whether out of a sense of moral imperative or simply because of a militant urge to fight, there are currently at least 300 active Western anti-ISIS fighters, including over 100 from the United States.

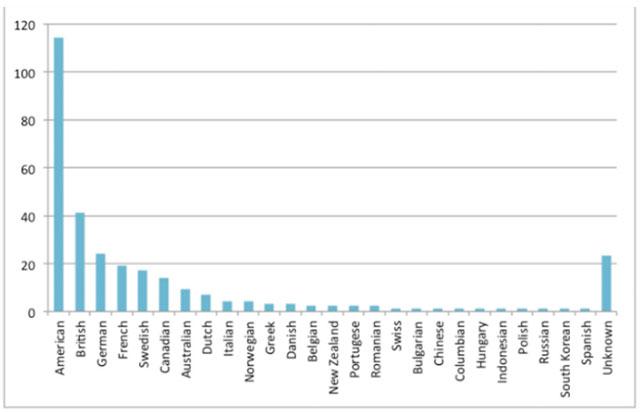

They hail largely from about 20 Western countries, including the United States, the U.K., Canada, and Sweden. They were identified during a year of research by the London-based Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD).

The think tank also found self-drafted fighters from corners of the world as far-flung as South Korea, Indonesia, and Colombia. The detailed report of their findings, “Shooting in the Right Direction: Anti-ISIS Foreign Fighters in Syria and Iraq,” was published in August.