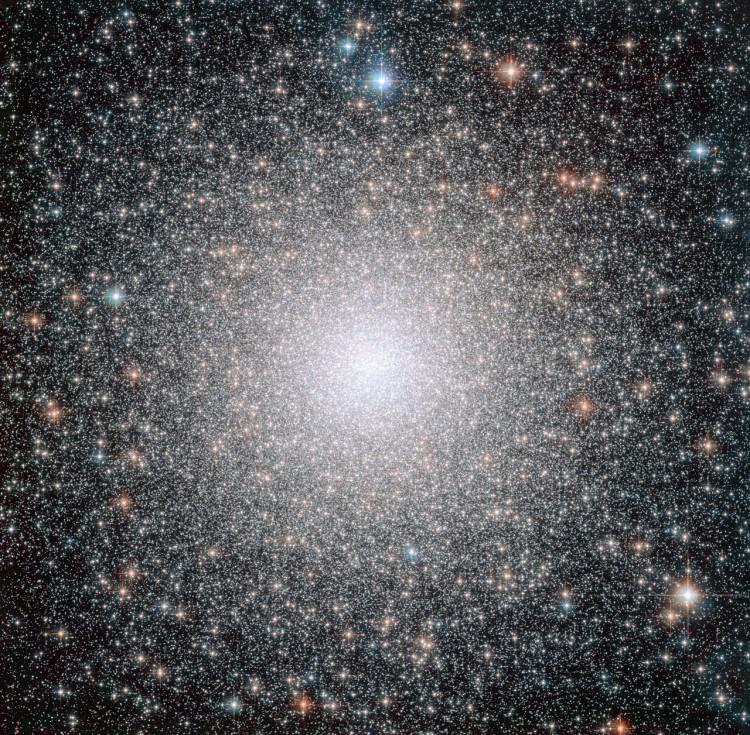

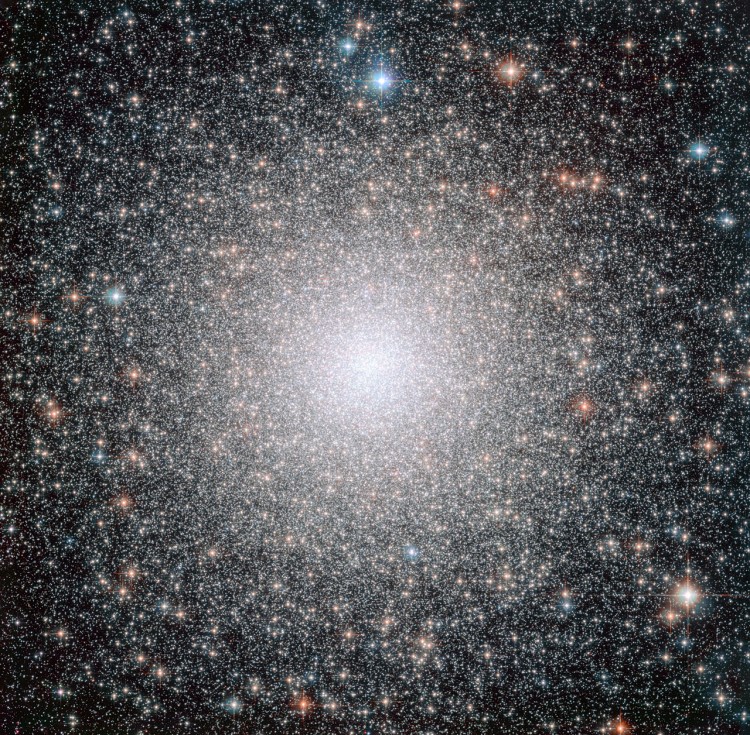

New research has shown that globular clusters may contain varied distributions of blue straggler stars, suggesting they age at different rates.

Globular clusters are bundles of stars bound together by gravity that formed relatively quickly in the early universe, and contain many ancient stars of similar ages.

Due to their age, only low-mass stars would be expected in globular clusters, because any high-mass ones should have already burned up.

However, bright, dense stars called blue stragglers can be present. They appear younger because they have gained extra fuel, for example in a collision.

“Although these clusters all formed billions of years ago, we wondered whether some might be aging faster or slower than others,” said research team leader Francesco Ferraro at Italy’s University of Bologna in a press release.

“By studying the distribution of a type of blue star that exists in the clusters, we found that some clusters had indeed evolved much faster over their lifetimes, and we developed a way to measure the rate of aging.”

As clusters age, gravity causes heavier stars to sink to the center, strongly affecting blue stragglers, which are fairly easy to spot due to their luminosity.

Based on their blue straggler distribution, three types of clusters were found: a few seemingly young ones with even distributions, numerous old ones with blue stragglers in the core, and some aging ones with central stars moving inwards, and more peripheral ones sinking to the center.

“Since these clusters all formed at roughly the same time, this reveals big differences in the speed of evolution from cluster to cluster,” said study co-author Barbara Lanzoni, also at the University of Bologna, in the release.

“In the case of fast-aging clusters, we think that the sedimentation process can be complete within a few hundred million years, while for the slowest it would take several times the current age of the universe.”

The study was published in Nature on Dec. 20.

The Epoch Times publishes in 35 countries and in 19 languages. Subscribe to our e-newsletter.