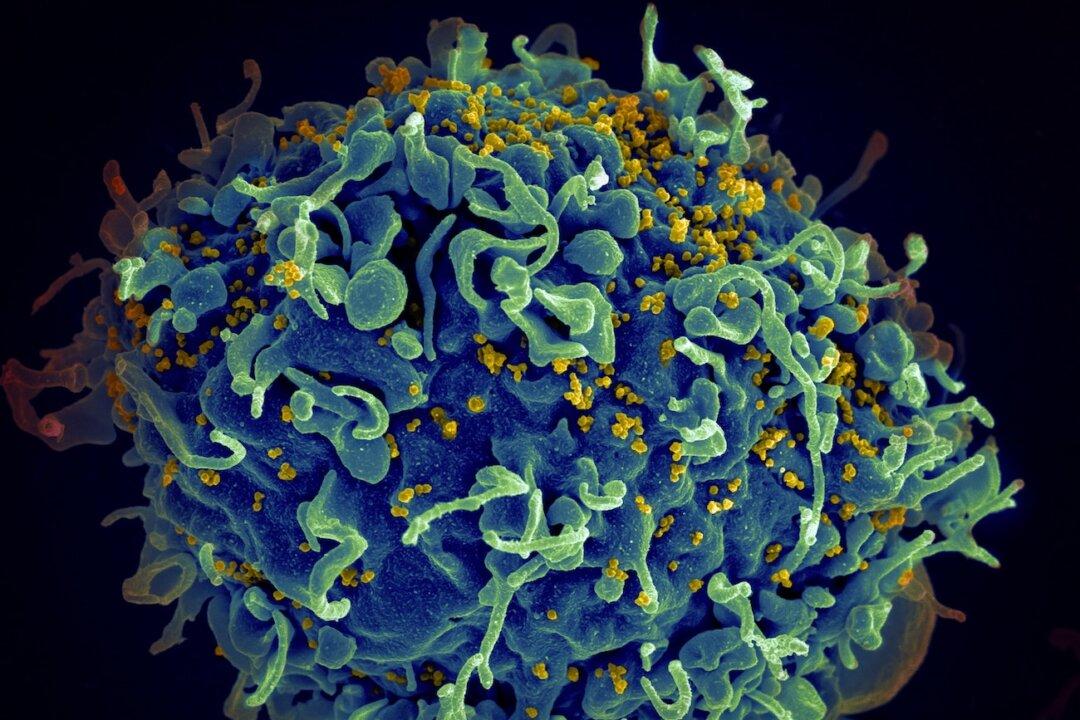

A human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) variant has been discovered in the Netherlands by researchers at Oxford University, who say the variant is highly infectious and more damaging than other HIV strains and can put individuals at risk of developing AIDS “much more rapidly.”

HIV is a virus that attacks the body’s immune system, which can but not always lead to AIDS if it isn’t treated. The World Health Organization (WHO) has estimated that between 30.2 and 45.1 million people were living with HIV at the end of 2020, with more than two-thirds of them (25.4 million) in the WHO African Region.