The following story is adapted from Bauerlein’s recent book, “The Dumbest Generation Grows Up: From Stupefied Youth to Dangerous Adults.”

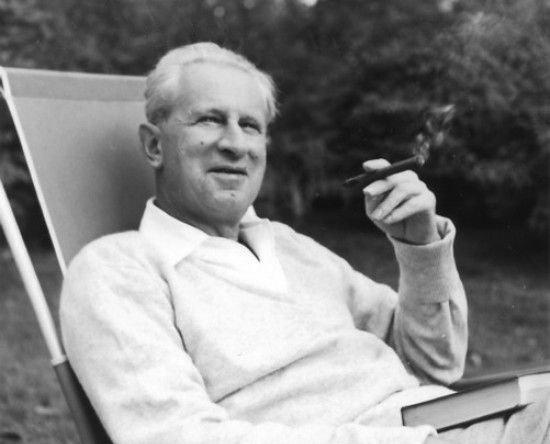

Back in April 1969, a surprisingly conservative thing happened at the ultra-progressive campus of SUNY–Old Westbury when radical theorist Herbert Marcuse visited to give a lecture to the students. Michael Novak describes the episode in his memoir “Writing from Left to Right: My Journey from Liberal to Conservative,” which includes a full chapter on Novak’s time teaching at Westbury, where he had joined the school as a willing participant in a new way of educating. The college had just opened with a small set of faculty and a hundred students or so. It was a deliberate experiment in youth empowerment. In this new institution “all students would be ‘full partners,’ and new ways of weaving together learning and action would be explored,” Novak remembers. Here, finally, teachers would respect the finer consciousness of students, who hadn’t been corrupted by the Establishment. Undergrads arrived fired up by Vietnam and youth revolt, convinced that the grownups had botched the world and wouldn’t let go unless the young forced them, and they demanded that Westbury show how authentic reform works. Many of the teachers agreed.