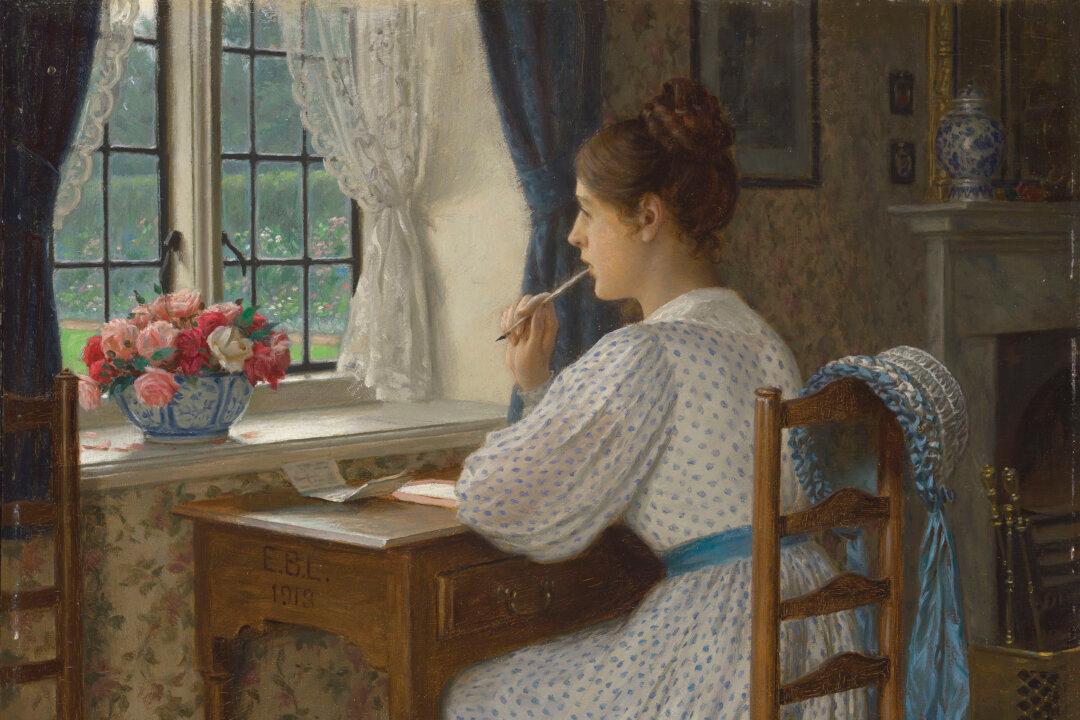

The beauty of her language and her affection for the departed make Edna St. Vincent Millay’s “Dirge Without Music” one of my favorite poems, yet even after many readings and teaching “Dirge” in the classroom, part of the poem still baffles me. Here are the last two stanzas.

“The answers quick and keen, the honest look, the laughter, the love,— They are gone. They are gone to feed the roses. Elegant and curled Is the blossom. Fragrant is the blossom. I know. But I do not approve. More precious was the light in your eyes than all the roses of the world. Down, down, down into the darkness of the grave Gently they go, the beautiful, the tender, the kind; Quietly they go, the intelligent, the witty, the brave. I know. But I do not approve. And I am not resigned.”As I say, beautiful words and rhythm, but the repetition of “I do not approve” and particularly “I am not resigned,” which occurs in the first stanza as well, confused me when I first read the poem and have bothered me ever since. To “not approve” death strikes me as an irrelevancy, like disapproving some act of nature: a hurricane, a blizzard, a tornado, even a cloudburst when it ruins your picnic. And “I am not resigned” also makes little sense, unless the poet means she will remember the dead as she has in this poem.

In the movie “Midnight In Paris,” we encounter another take on death and dying in this exchange between a young writer, Gil Pender (Owen Wilson), and Ernest Hemingway (Corey Stoll):

Gil: Were you scared? Hemingway: Of what? Gil: Of getting killed. Hemingway: You’ll never write well if you fear dying. Do you? Gil: Yeah, I do. I’d say probably, might be my greatest fear, actually. Hemingway: It’s something all men before you have done, all men will do.This view of death, that we must not fear it because it comes to us all, is also dissatisfying. Most of us do fear death, not just our own but the death of our loved ones. Those of us who have lost family members or a close friend know well the meaning of Millay’s line “More precious was the light in your eyes than all the roses of the world.” The death of someone dear to us leaves a gash in the soul. Eventually, time and circumstance repair that wound, but the scar remains.