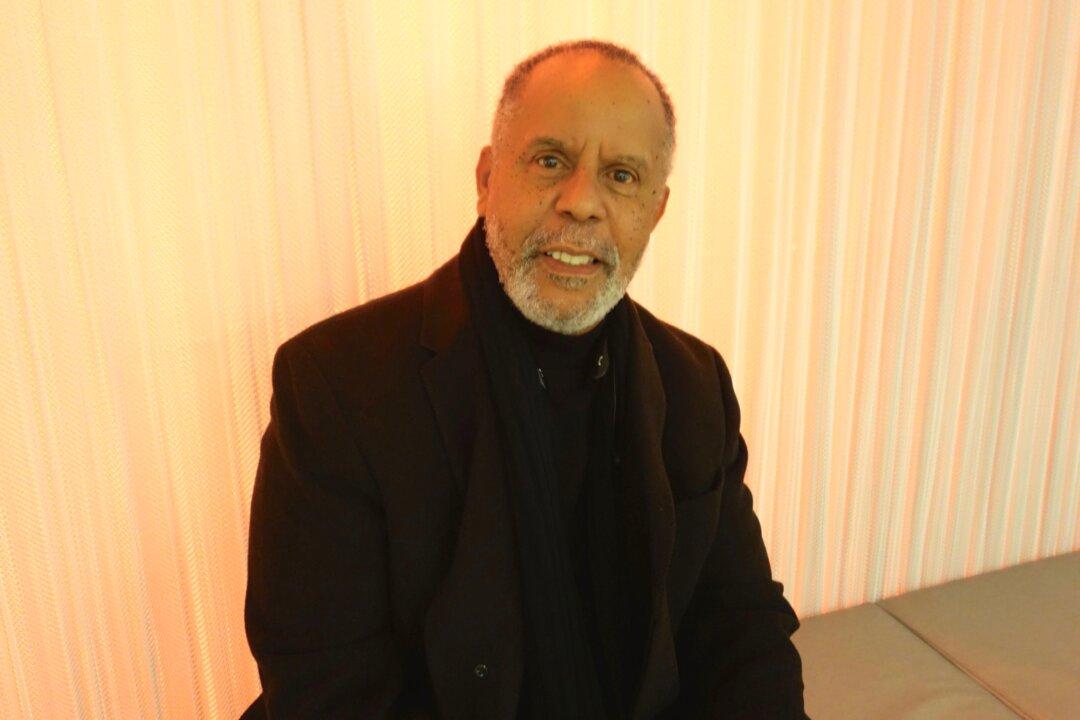

ATLANTA— Anthony J. Harris wore a crisp dress shirt and stood at a table stacked with copies of his three books, on June 14 at the Mississippi Picnic at Chastain Park in Atlanta, celebrating all things Mississippi. A Bully the Bulldog, costumed mascot of Mississippi State University, lumbered under the oaks, while two real bulldogs panted at the MSU table. A band played blues, and catfish was frying.

Harris had a Mississippi story to tell.

In 1964 when he was 11 years old, Anthony Harris went to a Freedom School in Hattiesburg, Miss., where folk singer Pete Seeger tried to teach him to play guitar. The music lessons did not take hold, he said, but other lessons stayed with him for the rest of his life.

The deepest lesson was not to allow himself to hate anyone. “Nonviolence. It was not just a tactic. It was a philosophy,” he said. He signed up to desegregate his middle school. “Kids are mean at that age,” he said. He heard racial slurs every day. Once two other boys spat on him in the hallway.

He mastered his emotions and walked on without retaliating. “I can be angry, but if I wallow in that rage I am no different.” His Freedom School teacher led him and others into the local white public library to apply for library cards. The librarian, beet red, threatened to call the police. He left with his head up.

Unprecedented

Harris wrote his autobiography, “Ain’t Going to Let Nobody Turn Me ’Round,” focused on Freedom Summer, which began in Mississippi on June 20, 1964. Civil rights groups invited college students to come to Mississippi to teach at Freedom Schools, tuition-free summer schools, and to register black people to vote, boosting a yearslong effort. About 1,000 mostly white students, clergy, and other adults traveled to Mississippi. “That was unprecedented. They were willing to risk their lives.”

On June 21, Klansmen murdered three of them, with collusion by local police.

Before James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner were killed, the rest of the country could think of Jim Crow in the Deep South as a regional issue that did not affect the whole country, according to Harris. But once white students were murdered, “this [was] a problem. Politicians in Washington had to take notice.”

The bodies were not found until August, hidden in a dam. The FBI arrested 18 men for the crime in October, but state prosecutors refused to try them. Many were shocked by the story, and it contributed to the passage of the Civil Rights Act that year.

Personal

The generation at the heart of the civil rights movement is diminishing. Many of them are gone, and some of them no longer have sharp memories, according to Harris. “I’m one of the few who can say I remember it directly. It’s not what someone told me about it. I was there.” His book is not a history of the whole civil rights movement, he said. He is not a historian. It’s a personal coming of age story. But he feels a mission to tell it.

“It’s a history we must acknowledge. We must not sanitize it.”

To him, understanding that watershed moment in American history is essential. To know just how violent and vicious the Jim Crow system was, and to know what people were thinking then, is important for “anyone who cares about our democracy.”

The Jim Crow legacy is not entirely gone, warned Harris. “Back in the 60s they did it with the poll tax. That’s what they did then. Now it’s you have to have this form of ID.”

He thinks 21st century Americans have to stay alert. “For those of us who fought for that [voting rights] we just can’t let it take hold.”

Harris is returning to Mississippi this weekend. He will be a panelist at an academic conference, Freedom Summer 1964–2014. The University of Southern Mississippi’s Center for Black Studies, in collaboration with the city of Hattiesburg, Hattiesburg Historic Downtown Association, and the Hattiesburg Convention Commission are honoring the anniversary.

This time, Dr. Harris will be able to stay in the library he entered so briefly in 1964. It’s hosting a book signing for him.

Harris teaches at Mercer University in Atlanta. He is featured in the PBS documentary, “Freedom Summer,” which will be released next week.