An attempt to label the thylacine’s hunting style has led to a new classification system that can predict the hunting behaviors of mammals from measurements of just a few forelimb bones.

The extinct marsupials had very dog-like heads but both cat- and dog-like features in the skeleton.

“We realized what we are also doing was providing a dataset or a framework whereby people could look at extinct animals because it provides a good categorization of extant forms,” says Christine Janis, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at Brown University.

For example, the scapulas (shoulder blades) of leopards—ambush predators who grapple with rather than chase their prey–and those of cheetahs—pursuit predators who chase their prey over a longer distance—measure very differently. So do their radius (forearm) bones.

The shapes of the bones, including areas where muscles attach, place the cheetahs with other animals that evolved for chasing (mainly dogs), and the leopards with others that evolved for grappling (mostly other big cats).

“The main differences in the forelimbs really reflect adaptations for strength versus adaptations for speed,” Janis says.

Scapulas Don’t Lie

As reported in the Journal of Morphology, cheetahs and African hunting dogs appear to be brethren by their scapular proportions even though one is a cat and one is a dog. But the similar scapulas don’t lie: zoologists knowledge both to be pursuit predators.

In all, Janis and Figueirido of the Universidad de Malaga in Spain made 44 measurements on five forelimb bones in 62 specimens of 37 species ranging from the Arctic fox to the thylacine.

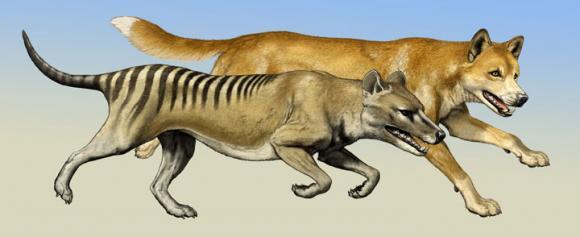

Unlike most modern-day predators, the extinct thylacine (foreground) may not have had a specialized hunting behavior, according to an analysis of its anatomy. Ancient Australia didn’t have a great variety of predators, so the thylacine was not under competitive pressure to specialize. (Carl Buell)

In various analyses the data proved helpful in sorting out the behaviors of the bones’ owners. Given measurements from all of the forelimb bones of an animal, for example, they could accurately separate ambush predators from pursuit predators 100 percent of the time and ambush predators from pouncing predators 95 percent of the time.

Results were similar for analyses based on the humerus (upper arm bone). They were always able to make correct classifications between the three predator styles more than 70 percent of the time, even with just one kind of bone.

The Thylacine Mystery

The thylacine has not been known on mainland Australia in recorded human history, and by official accounts it disappeared from the Australian island of Tasmania by 1936 (although some locals still believe they may be around).

In a similar vein, the beasts evaded Janis and Figueirido’s attempts at a neat classification of their mode of carnivory. By some bones they were ambushers. By others they were pursuers. In the end, they weren’t anything but thylacines.

They could do just fine as generalists, given their relative lack of competition, Janis says. Historically Australia has hosted less predator diversity than the Serengeti, for example.

“If you are one the few predators in the ecosystem, there’s not a lot of pressure to be specialized.”

In the thylacine’s case the evidence from forelimb bone measurements supports their somewhat unusual status as generalists by the standards of other predatory mammals. For other extinct predators, the framework will support other conclusions based on these same standards.

“One thing you tend to see is that people want to make extinct animals like living ones, so if something has a wolf-like head with a long snout as does the thylacine, although its skull is more delicate than that of a wolf, then people want to make it into a wolf-like runner,” she says.

“But very few extinct animals actually are as specialized as modern-day pursuit predators. People reconstruct things in the image of the familiar, which may not reflect reality.”

The Bushnell Foundation supported the study with a research and teaching grant. The Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University, the American Museum of Natural History in New York, and Australia’s Museum Victoria and Queensland Museum provided access to specimens for measurement.

Source: Brown University. Republished from Futurity.org under Creative Commons License 3.0.