In Georgia, four little words mean the difference between life and death for a small subset of people. The Supreme Court ruled in 2002 that the states must not execute a person with an intellectual disability.

In Georgia, and only in Georgia, a convicted murderer must prove to a jury that he or she has an intellectual disability, or ID, “beyond a reasonable doubt.” Because of that, convicted murderers who have almost certainly been intellectually disabled have faced the death penalty in Georgia.

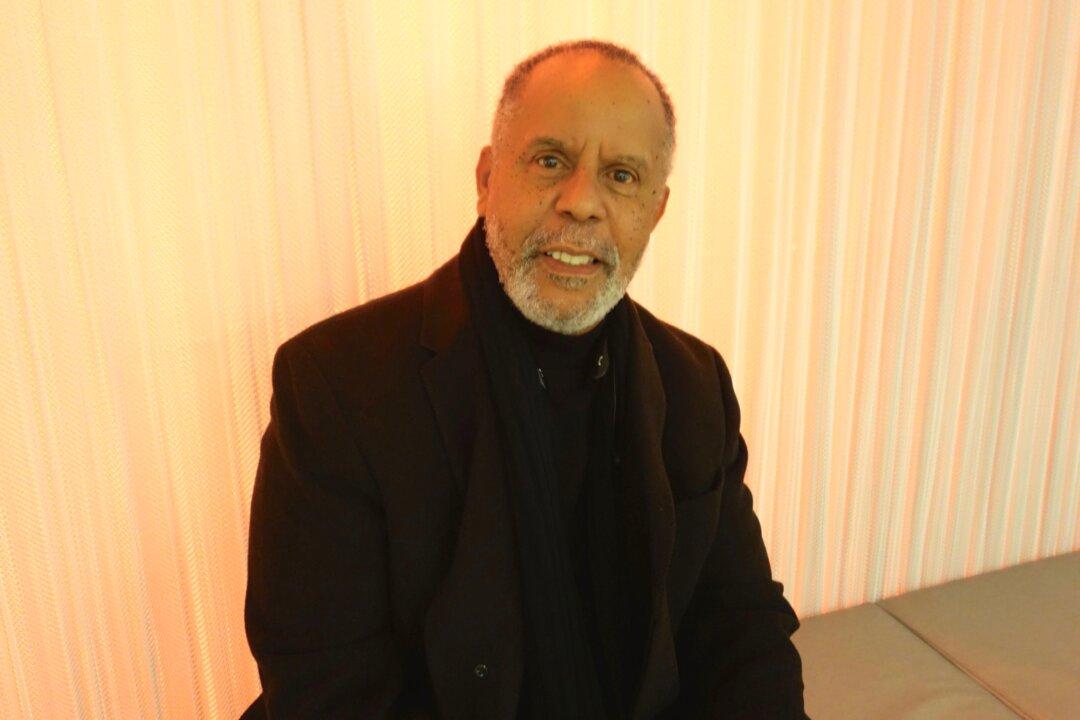

“I think life is precious, no matter how we look at it,” Eric Jacobson said. “To use the death penalty in cases where people have an intellectual disability—it’s not fair. It’s not justice.”

Jacobson is the executive director of the Georgia Council on Developmental Disabilities (GCDD). It is a federally funded, independent state agency that advocates on behalf of Georgians and families living with developmental disabilities, according to its website.

GCDD is not trying to end the death penalty. It is trying to bring Georgia in line with other states and to protect people with intellectual and mental disabilities from what the Supreme Court called, for them, “cruel and unusual punishment.”

According to Jacobson, “this is a population that should be taken out of the equation” for the death penalty. Jacobson and his allies want the standard of proof changed to “preponderance of the evidence.”