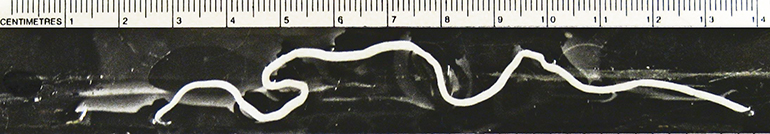

A parasitic worm that can grow to be almost a foot long and is known to infect raccoons has been found in cats in the United States for the first time.

To lay eggs that hatch into larvae, the female Dracunculus insignis worm must first emerge from its host. It forms a blister-like protrusion in an extremity, such as a leg, from which it slowly emerges over the course of days to deposit its young into the water.

“The problem is you can’t tell the exact species by looking at female worms,” says Araceli Lucio-Forster, a researcher in the lab of Dwight Bowman, professor of parasitology at Cornell University. “You need males to tell the species, because only they have distinct characteristics, such as different shapes of tail protrusions, to tell one from another.”

For a new study published in the Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery, Bowman’s lab collaborated with Dracunculus experts at the Centers for Disease Control to study sections of the worms in detail and conduct molecular analyses to confirm the identification.

Worms in the Dracunculus genus are well-known in human medicine. D. insignis’ sister worm, the waterborne Guinea worm (Dracunculus medinensis), infected millions of people around the world until eradication efforts beginning in the 1980s removed it from all but four countries with only 148 cases reported in 2013.

WATER AND FROGS

Other Dracunculus worms infect a host of other mammals—D. insignis mainly infects raccoons and other wild mammals and, in rare cases, dogs. It does not infect humans.

“The cats that contracted the worms likely ingested the parasites by drinking unfiltered water or hunting frogs,” Lucio-Forster says.

It takes a year from the time a mammal ingests the worm until the females are ready to migrate to an extremity and start the cycle anew.

While the worms do little direct harm beyond creating shallow ulcers in the skin, secondary infections and painful inflammatory responses may result from the worm’s emergence from the host. There are no drugs to treat a D. insignis infection—the worms must be removed surgically.

“Although rare in cats, this worm may be common in wildlife and the only way to protect animals from it is to keep them from drinking unfiltered water and from hunting—in other words, keep them indoors,” says Lucio-Forster.

Republished from Futurity.org under Creative Commons 3.0 license.

*Image of a cat via Shutterstock