What has been called a “quiet catastrophe” has been unfolding in America: the collapse of work for millions of America’s men, and, more recently, for America’s women as well.

Nicholas Eberstadt, the Henry Wendt Chair in political economy at the American Enterprise Institute, estimates there are 10 million men who are jobless and no longer looking for work. According to calculations using 2014 data, an estimated 3.6 million women are in the same situation.

President-elect Donald Trump has announced a raft of policies meant to spur economic growth and create jobs, but thought needs to be given to what specific measures might help this urgent situation.

How to address this crisis depends on what one understands the problem to be. A graph showing the prime-age employment rate for men provides a kind of Rorschach test for possible responses.

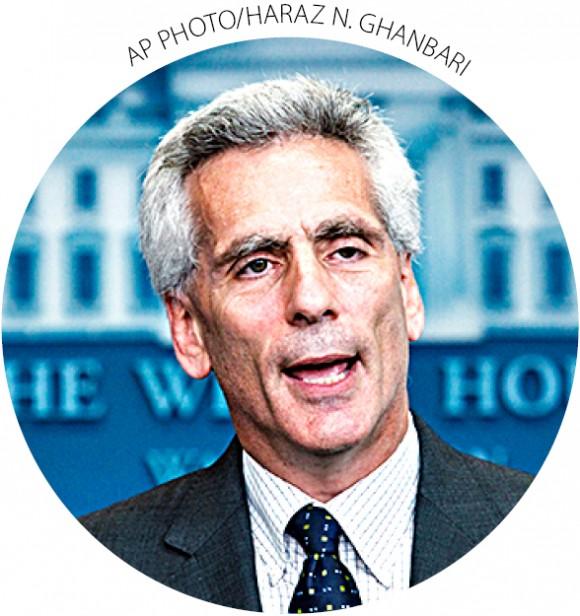

Jared Bernstein, senior fellow at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, former economic adviser to Vice President Joe Biden, and author of, most recently, “The Reconnection Agenda: Reuniting Growth and Prosperity,” focuses on the cyclical upturns in the jagged line, on those periods of prosperity when workers regain jobs that had been lost.

Eberstadt focuses on the straight trend line, which has been going inexorably and disastrously downward for decades.

Bernstein and Eberstadt represent two typical and contrasting approaches to the unemployment problem.