When parents and children enjoy being together while learning and improving skills, it creates the perfect conditions for strengthening family relationships and enhancing lifelong learning.

These are some of the goals of family literacy, which focuses on interactions between generations in the family and community that foster a culture of learning and the development of literacy and other life skills.

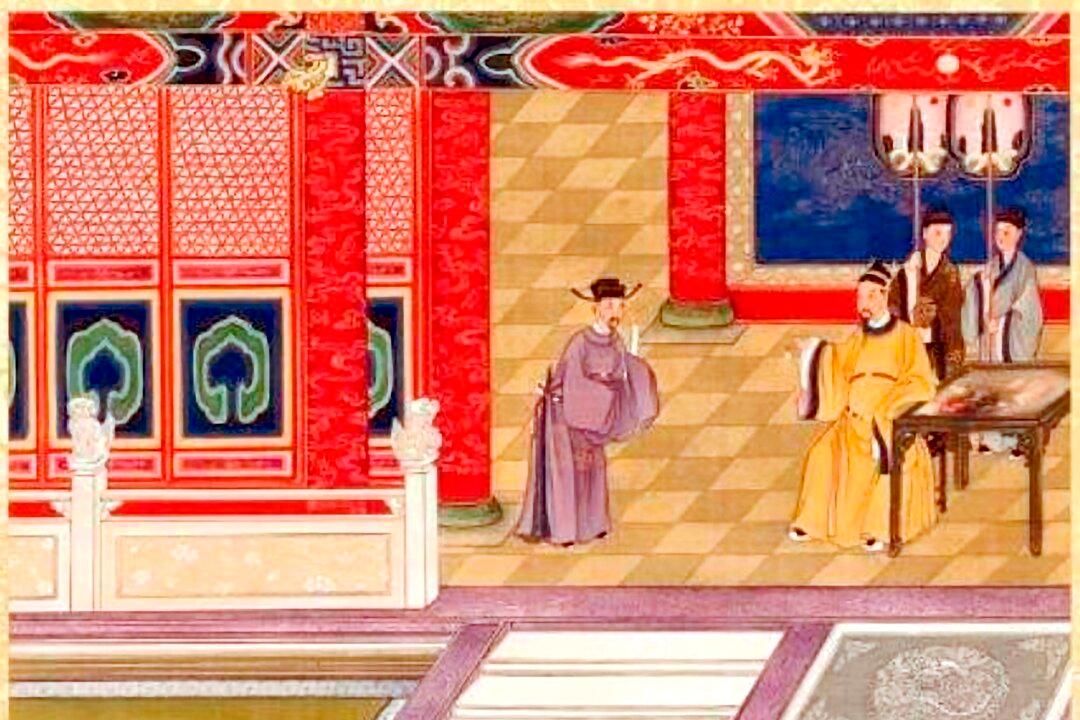

Inter-generational teaching and learning are longstanding traditions rooted in many cultures.