“Mr. Automatic” is the name regularly pegged to placekickers in the NFL. But changes for at least one year in the point-after-touchdown are hoped to make things less automatic and add an air of unpredictability. Since 2004, placekickers have a success rate on extra points of over 99 percent, making PATs one of the most boring plays in football. Needless to say, placekickers are expected to be spot-on no questions asked.

Under the new rules, copied from the Canadian Football League, the ball gets spotted at the 15-yard line for extra point attempts, though it leaves the 2-point option from the 2-yard line intact. The change also allows the defense to run back a blocked or botched kick for two points.

But will the rule change deliver a glossier product? Is it enough to keep fans in their seats, in suspense, for the point-after-touchdown? Two missed extra points in the first week of the NFL preseason doesn’t portend much of an uptick in excitement. Minnesota Viking placekicker Blair Walsh reminded ESPN that the new distance equates to a chip shot 33-yard field goal, made 97 percent of the time last season. He thinks any difference will manifest in late fall in the cold and wind.

The near-perfect results in placekicking might be attributed to the emergence of foreign-born soccer-style kickers, who drew sharp language from All-Pro lineman Alex Karras with the Detroit Lions. “Tighten immigration laws,” he quipped.

The first were Cyprian nationals Charlie and Pete Gogolak, who, in 1966, combined for 14 extra points in Charlie’s Washington Redskins 72–41 rout of the New York Giants. Hungarian-born Garo Yepremian, who passed away in May, is remembered for two things: His kick that ended the longest game in history on Christmas Day 1971 and, over a year later in Super Bowl VII, the ball, as if a hot potato, he served for an interception on a botched field goal snap and returned for a touchdown.

The gist of the ire was that kickers like them didn’t know a lick about American football.

“I keek a touchdown,” Yepremian famously rejoiced after his first-ever extra point.

Karras’s objection was over specialists with clean jerseys trotting in and deciding the game. After all, there was a time a football kicker did other positions. And they fared quite well.

Bob Timberlake, a backup quarterback for the 1965 New York Giants doubled up as a place kicker. With respect to his low point 0–15 on field goals, his 21–22 PATs weren’t a significant drop off from the modern era.

Lou Groza, an offensive tackle for the 1950s and ‘60s Cleveland Browns kicked his way to the Hall of Fame with a lifetime PAT percentage of 97.6. Defensive tackle Lou Michaels of the Baltimore Colts made 388 of 401 extra points, or a 96 percent rate. Hall of Fame halfback Paul Hornung of the Green Bay Packers handled the kicking and made 190 of 194 PATs, or 98 percent, in his career. The late sportscaster Pat Summerall, also an offensive end, went 100 percent in PATs one season.

Forty-three-year-old Oakland Raider George Blanda quarterbacked against the Colts in the 1971 championship. Besides completing 17 of 32 passes and two touchdowns, he kicked a 48-yard field goal and two extra points. Blanda ended his career with 943 of 959 in extra points.

Mark Moseley of the Redskins was the last of these so-called straight-on kickers in 1986. His lifetime PAT rate is low by contemporary standards at 94 percent.

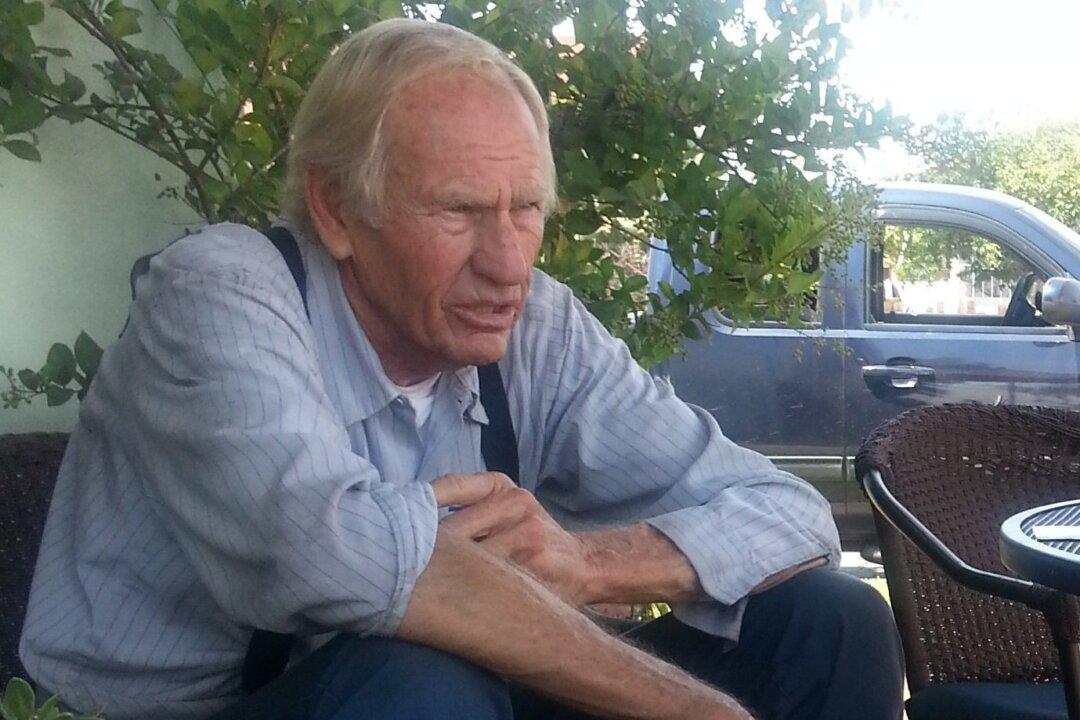

A former defensive end under legendary coach Vince Lombardi at Green Bay and Washington offered a keen perspective on modern-era specialists versus kickers of old who played other positions. “Back then there were just 40 on a team and players had to play other positions,” says Leo Carroll, now owner of a muffler shop in Alhambra, Calif.

The NFL’s tweaking of extra points is reminiscent of Lombardi’s words: “Gentlemen, we will chase perfection, and we will chase it relentlessly, knowing all the while we can never attain it. But along the way, we shall catch excellence.”

Consensus on the rule change seems to be that little change in making the game more exciting is imminent. “[This amounts to] how to make a boring play no one really cared about into a still-boring play no one will care about,” states columnist Chris Chas of USA Today.

One viable consideration is that severe weather condition may force a coach to opt for a 2-point attempt instead.

Still, since football is a cousin to rugby, mightn’t the NFL teams themselves consider dusting off the antiquated drop kick? Used for the first (and last) time since 1941 by Doug Flutie of the new England Patriots in 2006, the oblong ball presents a myriad of chance bounces that would make extra points far less certain—and renders the possibility for more excitement. Considering the slow-to-change culture of the NFL and its teams, the drop kick replacing the place kick is about as likely to take shape as Gustavo Dudamel and the Los Angeles Philharmonic being chosen to perform at the Super Bowl.

Timothy Wahl’s experience in business, education, the sciences, and the arts gives him a unique platform on a spectrum of subjects.