Want to save forests? Don’t forget the youth, says Pedro Walpole, the Chair and Director of Research for the Environmental Science for Social Change, a Jesuit environmental research organization promoting sustainability and social justice across the Asia Pacific region.

“Youth leadership in environmental management is key,” Walpole told mongabay.com. “Most of all we have to learn from the youth what are their insecurities and challenges in engaging in what will become the era of sustainability and simplicity rather than development.”

Currently living in Mindanao in the Philippines Walpole says much of his time is spent “focused on peace building and serving the educational and ecological interests of the Pulangiyen people through the Apu Palamguwan Cultural Education Center which promotes mother tongue-based, multilingual education for peace in the area."

“What gives me hope now,” Walpole says, “is our work with youth and attitudes, where we strive to build capacities among youth in various aspects of ancestral domain management through rediscovering a sense of belonging, and how the forest is valued in the culture…Sadly, these are what international financial institutions and other development organizations consider as ’software' assistance that can be done in the periphery of a forest-focused investment, rather than as a central strategy for achieving the goal of sustaining the multiple services that forests provide.”

Beyond his work with ESSC, Walpole has worked with theAsia Forest Network; helped establish a Task Force on Jesuit Mission and Ecology which wrote the document“Healing a Broken World” that offers practical approaches toward “reconciliation with creation' through faith, justice, inter-religious and cultural dialogue.” He also works with the online publication Ecojesuit, as well as Healing Earth— a new approach to environmental education led by the Loyola Chicago University.

“I think that talking about forest conservation in the context of Asia and other developing countries where basic needs are not met among people who live with the forest is not realistic,” Walpole said. “It is better to first understand how people value the forest, and know the pressures; from this point it is better to nurture those attitudes while applying the needed political accountability. What can sustain ecosystems is if we can have a long-term people-focused approach.”

He adds that “conservation in many cases is distant and is not lived integral to the human spirit; it often boxes personal preferences and fails to call upon the more humble nature of human community to care for life.”

An Interview with Pedro Walpole

Mongabay: What is your background? How long have you worked in tropical forest conservation and in what geographies? What is your area of focus?

Pedro Walpole: I started working on conservation issues at 15 when I lobbied with local authorities not to convert the woodlands and corncrake (Crex crex) wastelands nearby my home to another urban sprawl. They remain I am told. At 17 I got a job at London Zoo, Whipsenade, and went to meet Peter Scott on the Severn. I found an opportunity to work with Sabah National Parks as an ecologist based on Mt. Kinabalu and study the altitudinal evolution of species. Joined WWF in its documentation of Bodgaya and Sipadan Islands and went down the Kinabatangan before it was logged. I took an interest in megapodes (Megapodius cumingii cumingii). I started to track the different species all the way to Australia and this lead me across the waters to the Philippines. The forests and seas I passed through were beyond the reach of governments and services; the people I met along the way had no support to meet their needs and were in many cases simply refugees. Conservation was an attitude held by few and had little appreciation of cultural history or community crisis at any given time.

The local knowledge, spirit and cultural ecosystem of living as part of a land/sea scape outshone any textbooks and academic discourse. Such discourses often appear apolitical but are not, while being scientific and rational they are “anecdotal” in the sense of a daily living earth. The journey leads me to realize that talking about conserving megapodes and the supporting ecosystems is inadequate in approaching the challenges of our disconnected human society. Conservation in many cases is distant and is not lived integral to the human spirit; it often boxes personal preferences and fails to call upon the more humble nature of human community to care for life, and live life in the same daily world. Along the way, I focused on watershed assessments analyzing the dynamics of forest land use change in various parts of Asia.

From Srinagar to the Salween to Zamboanga, national conflicts divide people, lands and all that is good. Today, global corporate investments of limited accountability blaze their own trail, with mining, hydro and monoculture infrastructure oblivious to human cultures determined to command the only allowable way forward to blinkered consumption. From Kunming to Narathiwat and Mawlamyine to Da Nang, millions of people are caught in every quarter of the crosshairs of that energy development and commodification of resources over livelihoods. This is the broad base call for environmental conservation of people livelihoods forest and water, not a limited and isolated action.

Mongabay: Are you personally involved in any projects or research that you feel represents emerging innovation in tropical forest conservation?

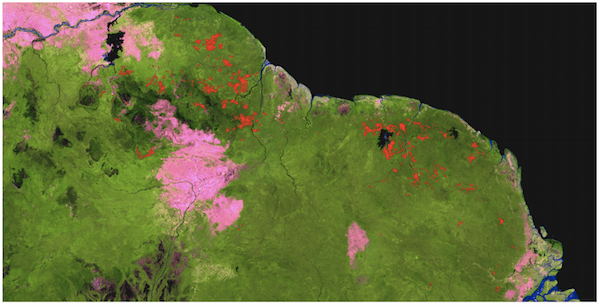

Pedro Walpole: I work through the Environmental Science for Social Change, a Jesuit environmental services organization providing technical and scientific analysis and research that includes the use of remote sensing and geographic information systems. Building on the mapping tradition of turn-of-the-20th century Jesuits in the Philippines, I thought that it would be good to show how critical the country’s forests are, but the decline and loss of island ecosystems over the past 100 years is staggering.

In 1999, we launched a map and booklet on theDecline of the Philipine Forest showing how and why the country lost its forests and what can be done about it – basically through promoting the role of local communities in forest management including ancestral domains. Soon after, through disseminating the poster map on Phillipine Cultures and Ecosystems, we helped provide evidence that where there are forests, there are more likely to be indigenous peoples. My work on Forest Faces gave me a chance to express voices from the forests and simply what forests mean in peoples’ lives from different sectors of society. Work in forest hydrology more recently brought me down the slopes to areas of disaster risk reduction, in an effort to communicate widely a greater and more comprehensive understanding of the real causes and dangers of landslides and flooding as they occur in different contexts.

I support the role of local communities in the protection and sustainable use of Asia’s forests through theAsia Forest Network. Through AFN, I supported and tracked the uptake of community forest management policies in Southeast Asian countries in the first half of 2000, and later on asked the question —Where is the Future of Cultures and Forests?

I joined a group that explored the rationale for establishing a Task Force on Jesuit Mission and Ecology in 2010. The resulting document is“Healing A Broken World” that offers principles and recommends practical approaches toward ’reconciliation with creation' through faith, justice, inter-religious and cultural dialogue. Afterwards, I was tasked by theJesuit Conference of Asia Pacific (JCAP) to track and animate actions that operationalize these recommendations in collaboration with other Jesuit people the region. The main communication of this is throughEcojesuit where a global engagement of many of the universities and social research institutes tackle a more integral sense of a living earth and human responsibility and hope. Healing Earth lead by Loyola Chicago University is a new approach to environmental education with a local to global relation.

An emerging sustainability camp through the Ateneo de Manila University for Masters students of business administration seeks to engage globally in what sustainability is at the local level and how to work with local initiative. These and multiple other efforts to network are part of a growing effort from concern for the Amazon to fossil fuel divestment and entrepreneur/livelihood investment that people seek to participate in and learn how to work with the challenges of the coming generation. Most of all we have to learn from the youth what are their insecurities and challenges in engaging in what will become the era of sustainability and simplicity rather than development. We need to celebrate not as an extravaganza but as personal and community deepening while seeking with others the aspirations of a good life (el vivir bien) for all. Youth leadership in environmental management is key.

My hamlet home along Pantaron Range in Mindanao keeps me rooted in the life of people in lower montane forests, where much of my time is focused on peace building and serving the educational and ecological interests of the Pulangiyen people through their domain (gaup) and the Apu Palamguwan Cultural Education Center that promotes mother tongue-based multilingual education for peace in the area. The youth know their forests by protecting the mother trees and regenerating springs that will be needed to sustain the landscape as they work for better resource management and integrated ecosystems allowing for local livelihoods and biodiversity.

Mongabay: What’s the next big thing in forest conservation? What approaches or ideas are emerging or have recently emerged? What will be the catalyst for the next big breakthrough?

Pedro Walpole: I think that talking about forest conservation in the context of Asia and other developing countries where basic needs are not met among people who live with the forest is not realistic. It is better to first understand how people value the forest, and know the pressures; from this point it is better to nurture those attitudes while applying the needed political accountability. What can sustain ecosystems is if we can have a long-term people-focused approach to building capacities in the sustainable management of the landscape and waterscape of which forests and people are part.

On another level, central to a global society is taking the time out to know self, our relations, and the planet we live on. The dialogue of science and values is most critical; our consumption, needs, and attitudes are not merely personal but relate with a deeper sense of community.

From my experience, I find that things work when people’s relations with the forest are nurtured, as part of the broader goal of “healing a broken world” through reconciling with creation, self and others. What gives me hope now is our work with youth and attitudes, where we strive to build capacities among youth in various aspects of ancestral domain management through rediscovering a sense of belonging, and how the forest is valued in the culture. Learning, focusing, collaborating and synergizing are the seeds that are bringing us forward. Sadly, these are what international financial institutions and other development organizations consider as “software” assistance that can be done in the periphery of a forest-focused investment, rather than as a central strategy for achieving the goal of sustaining the multiple services that forests provide.

Mongabay: What do you see as the biggest development or developments over the past decade in tropical forest conservation?

Pedro Walpole: Forty years ago, it was not possible to talk with government about considering local communities as forest managers. Thirty years ago, the idea of securing tenure of indigenous peoples in forest areas was out of bounds. It is only over the last 20 years that some sections of mainstream society have learned to warm up to the idea that sustaining forests cannot just be left to foresters, silviculture practitioners, botanists and biologists; other perspectives need to come in given the socio-political complexity of the issues and the many ecological services that forests provide which people value. In the past decade, with a focus on achieving the Millennium Development Goals, forests have become a platform for acknowledging people in the forest margins and putting them in the mind map of government agencies and politicians. There is also increased realization with climate change that what people do for forests contribute not only to the local and national, but also to the global. Forests have come to the forefront of global concern because of their contribution to mitigating climate change as well as their role in helping people adapt to the already changing climate. Much still has to be learned, especially in how to effectively collaborate with one another.

Mongabay: What isn’t working in conservation but is still receiving unwarranted levels of support?

Not that it is receiving unwarranted levels of support, but management of protected areas, including national parks, has to incorporate the notion of human security. Changing the boundaries of national parks without local consultation like with the Nagarahole tribal people in India, or the invasion of indigenous land by national and trans-national development and corporate markets from Brazil to Bolivia should not happen anymore.

We need to remember that we are not just individuals; we also come from dynamic communities and institutions. When we do research as scientists, the obsession with data needs to be accompanied by an understanding of the methodology. We need capacity cooperation and locally-grounded engagement.

Forestry departments need a redefinition and role in societies and a far greater awareness of the limited role plantations have as fast growing monocultures in relation to the ecological and cultural services of permanent indigenous forests. REDD+ financing mechanisms need to strive beyond just working on social safeguards, towards recognizing that indigenous peoples and local communities need to be at the center of the strategy. We really need to depend upon and support the people living in these areas to have their own sustainability and opportunity.

This is why I would rather not talk about conservation and protection, but instead about relations and sustainability.

This article was originally written and published by Liz Kimborough, a contributing writer for news.mongabay.com. For the original article and more information, please click HERE.