It’s a hotbed of forward-thinking collaboration between business, government, and academia. It’s (drumroll) Oklahoma.

The drones are as high as an elephant’s eye.

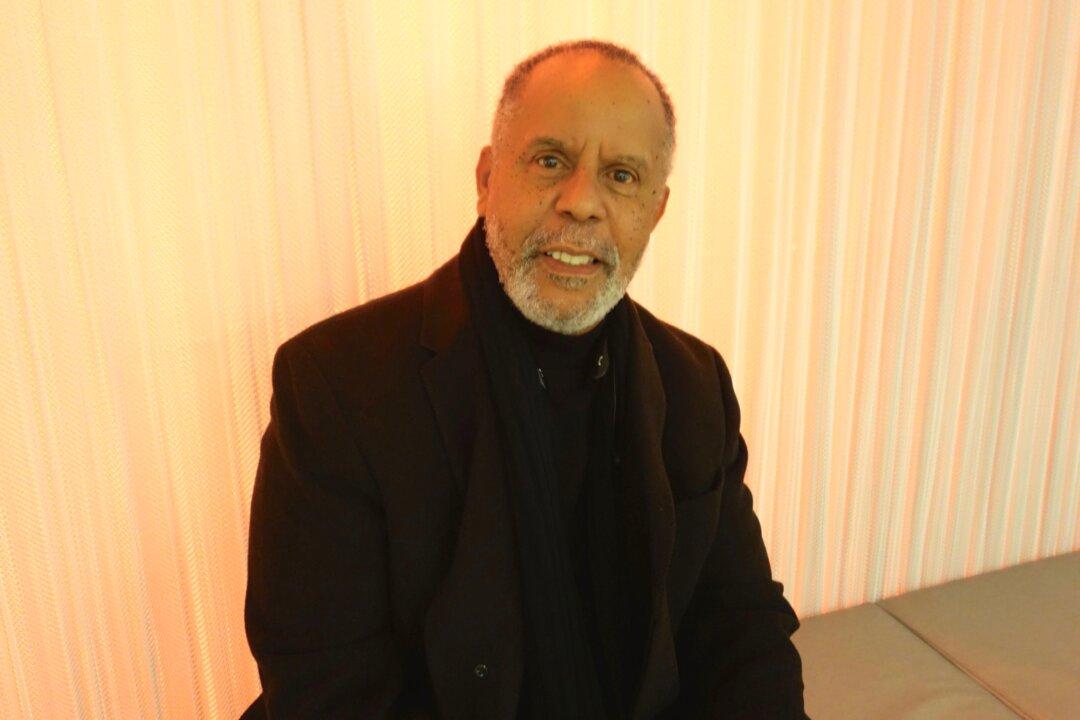

Oklahoma Governor Mary Fallin appointed a physicist to her cabinet in 2011. His mission is “to transfer new technologies and research into commercial opportunities for the benefit of our local and state economies,” said Dr. Stephen McKeever, state Secretary of Science and Technology, in a statement when he was appointed.

He has expertise in unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), AKA drones, AKA UAS, unmanned aerial systems. Oklahoma is a national leader in the technology.

Great Support

In an interview, he downplayed his role in Oklahoma’s innovations, giving credit to the governor, the military, local businesses, the aerospace industry, and the state’s university system. State legislators, federal agencies, and Oklahoma congressional leadership have all understood the technology’s potential. “Great support there, great,” he said. Cooperation has been essential.

Oklahoma has had a very active research and development plan since the mid-1990s, according to McKeever. It established the Unmanned Aerial Systems Council “before it was popular,” he said. That’s why the state is a leader in UAV technology today.

Oklahoma colleges “especially Oklahoma State University,” have been producing people with undergraduate and post-graduate skills in the field. They understand UAV design, electronics, and payloads.

Those graduates are able to design UAVs for different uses. “You design the vehicle for a particular application. It’s not one size fits all,” McKeever said.

Agriculture is one of most important UAV uses. Farmers can monitor crop health and water needs using UAVs.

Disaster recovery, fire fighting, and search and rescue are another key application.

Test Site for Homeland Security

Oklahoma was chosen to be a test site for drone use for the Department of Homeland Security, said McKeever. For example, they are working on how to use them to rescue people trapped after tornadoes, to monitor dangerous weather, to find lost people, and to fight fires.

Oklahoma applied to be a UAV test site for the FAA, but was not chosen, he said, and sighed. The FAA chose North Dakota instead.

The oil and gas industry is another key application for UAVs. Alaska has recently begun using them to monitor pipelines. The FAA approved the first commercial drones over American soil in June, when it gave BP permission to use them to check pipelines and other infrastructure on the fragile North Slope. The UAVs may be able to spot leaks or cracks before they become disasters.

Opportunities, Risks

“These surveys on Alaska’s North Slope are another important step toward broader commercial use of unmanned aircraft,” said Transportation Secretary Anthony Foxx in a statement. “The technology is quickly changing, and the opportunities are growing.”

While opportunities grow, risks grow. This past Saturday a videographer’s private drone nearly interfered with firefighting aircraft in Northern California. The pilot brought his vehicle down after authorities asked him to do so, and no harm resulted. But dangers to privacy and to aviation raise questions, and may be one of the reasons the FAA has been slow to give permission for commercial UAV use in America.

Any reasonable person might ask about aviation threats and dangers to privacy, said McKeever. On the other hand, existing laws already protect American’s privacy. “As citizens, we have the Fourth Amendment.” Even though many things exist now that the Founding Fathers could not have imagined, it has not been necessary to change it. It still works.

Peeping Tom

Oklahoma has a state Peeping Tom law that forbids stealth photography of a person’s private realm. “It does not say the camera has to be hand-held,” said McKeever. It gives a legal basis to forbid sneaky drone filming.

Photographer Tom Hoebbel, based in Ithaca, N.Y., said in an email he does not understand “any restrictions based on privacy concerns. I am limited by the same privacy laws in drone photography as I would be in any other sort. To be honest, the drones are not subtle.” It would be harder for him to use UAV to get a stealth photo than it would be to do it another way.

McKeever hopes that people will not develop restrictive laws without examining whether current laws already address the issues.

Privacy is less important when speaking of agricultural uses, according to Beau Dealy, Unmanned Aerial Systems Analyst and Managing Partner with Apis Remote Sensing Systems. Also, in rural places there is less chance of collisions with other craft. Apis is based in Kansas.

“Not everyone wants a robotic aircraft in their barn, but there’s not anyone I’ve talked to that doesn’t want the field knowledge obtainable from it,” said Dealy.

He is eager for the FAA to give a green light. His company sells the AgEagle “which is a UAV engineered from the ground up for use in agriculture,” he said in an email. His UAVs carry specialized near-infrared cameras that can measure whether a crop is stressed so that farmers can take action.

In his opinion the FAA needs to let commercial UAV use happen widely so that the government has baseline data to decide what policies, rules, or regulations are needed.

Chickens, Eggs

“I understand that job 1 of the FAA is to keep our skies safe. However, this is a ”chicken and egg“ problem. How can the FAA set guidelines without first having good data to understand use cases? Privacy isn’t really a concern to corn and cattle,” wrote Dealy.

As for aviation safety, it calls for technical solutions, according to McKeever. In a piloted plane, you can see and avoid “something coming across your bow.” UAVs might use satellite signals, radar, transponders, and other sensing and signaling devices to avoid collisions.

Speaking of both safety and privacy, it’s necessary to balance risks and benefits, according to McKeever.

The FAA is never going to promise that there will not be an airplane crash. What it can do “is mitigate risk” through training, policy, best practices, and technology, according to McKeever. The same things can and should be developed for UAVs.

The benefits can be huge. “If someone had told you five or ten years ago that you would carry a device with a camera, and a microphone, and a GPS, that could show where you are, that could be turned on and listen to you without you knowing it, you would have refused.” Yet we all carry smart phones today because the benefits outweigh the risks, said McKeever.

Drones may have unimaginable benefits. Entrepreneurs are likely to think of valuable uses and start businesses based on them, creating things that will make our lives easier and better, according to McKeever.

Out in the heartland, he is working to bring those benefits to life.