The “adjudication” feature of Dominion Voting Systems, which allows operators of the software to change votes on a ballot, has been cast into the spotlight after an audit of the system in one county revealed a particularly high tabulation error rate, indicating that the system may have been sending large numbers of ballots for adjudication.

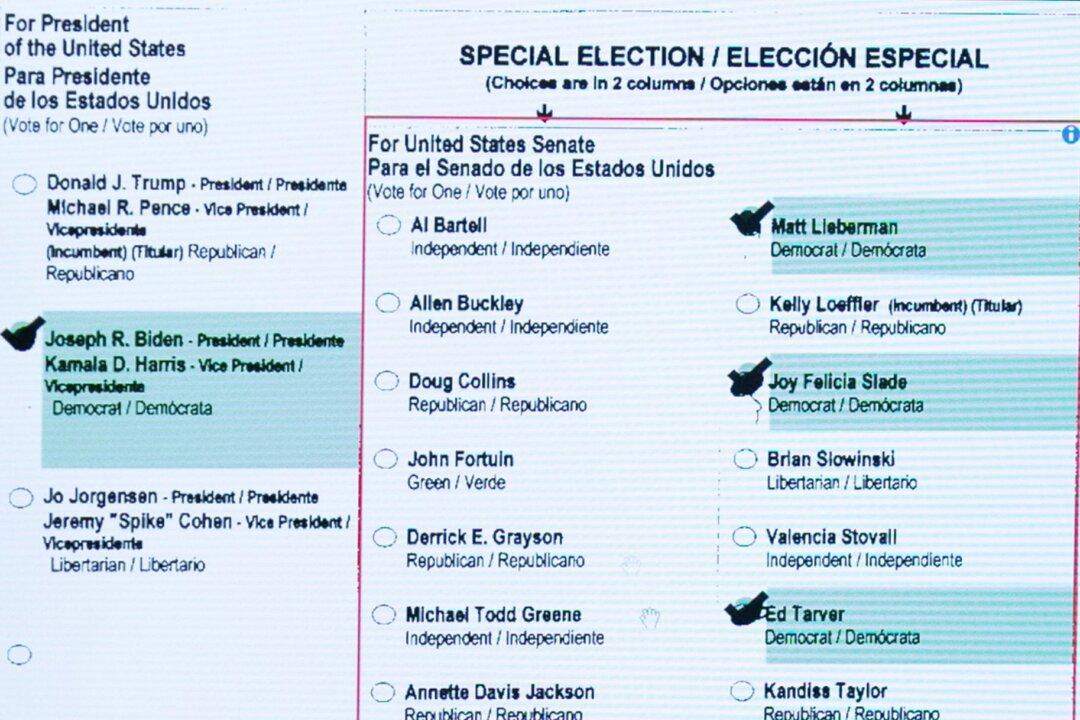

Some states allow election officials, under bipartisan supervision, to try to determine who a voter intended to vote for on an incorrectly filled-out ballot, instead of tossing the ballot.