News Analysis

In his recently published commentary article, Yu Keping, a member of a think tank that served former Chinese leader Hu Jintao, has challenged long-standing official narratives by casting a positive light on the Russian transition to democracy.

Yu’s article, titled “Important Gleanings From Russia’s Democratic Reformation,” was published online by Caixin, a leading Chinese financial news media group based in Beijing.

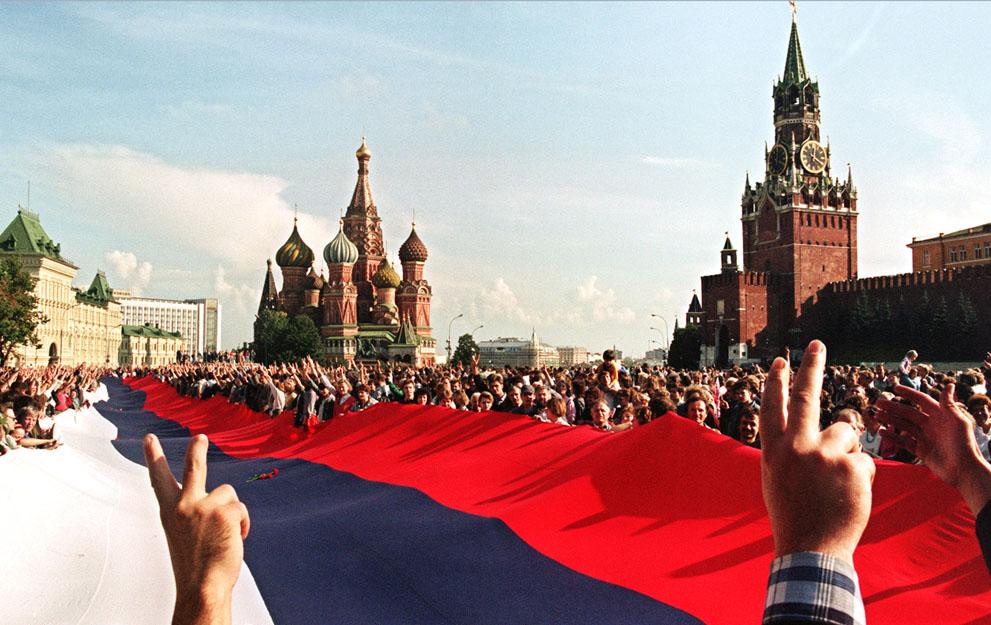

With its take on the democratic reforms started by Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev that ultimately led to the end of communism in Eastern Europe, the piece flies in the face of what China’s state-approved pundits and top officials have been saying for years: that introducing political freedom was a disastrous betrayal of international socialism.

“Following the disintegration of the Soviet Union, Russia embarked on political reformation in a democratically-oriented direction,” Yu writes.

“This is an event of major significance in 21st-century political history. Not only has this enriched the pluralization of popular modes of political development, but also the popular understanding of the principles governing political development.”