*

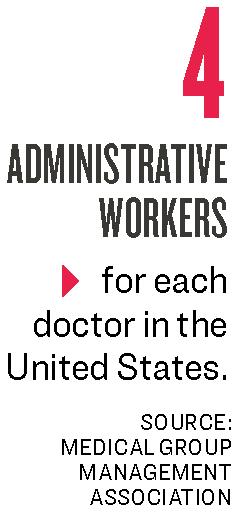

The growing complexity of the health care system has beset doctors with mushrooming bureaucracy, raising costs for patients and taxpayers.

Running a doctor’s office naturally invites paperwork, from booking appointments to maintaining health records to bookkeeping. But a deluge of additional paperwork floods in when a doctor asks to be paid.

Doctors navigate dozens of funding streams, each a bureaucratic labyrinth brimming with forms to fill out and rules to follow. In addition to Medicare, Medicaid, and military insurance, there are dozens of other insurance companies, each with a unique set of requirements.