Commentary

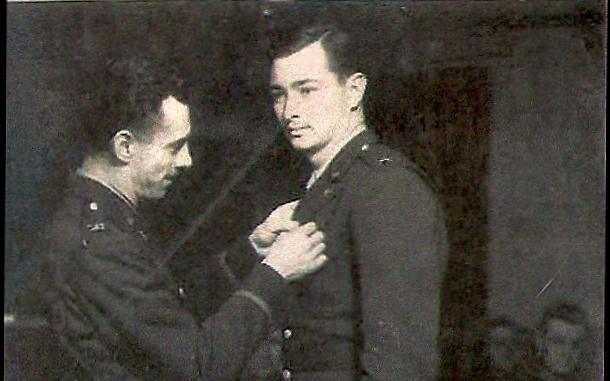

He was six-foot-four-inches tall. Born May 11, 1919, in Houston, Texas, Harold Johnson would have been a giant among the English during World War II. This American war hero gave his medals to a little boy who sat next to him on a train on the first leg of his journey home from England. He completed 40 missions navigating B-24 bombers over Germany and France. That was the ticket home for U.S. Army Air Corps flyers. He died in a tragic road accident on June 11, 1951, leaving his wife and three young daughters without their father. His now grown children would like to find that little English boy.