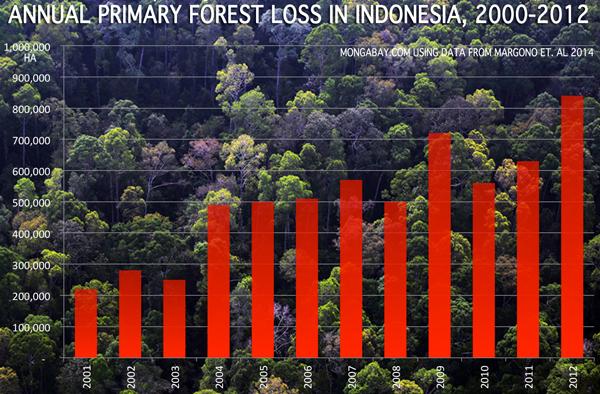

Despite having a deforestation rate that now outpaces that of the Brazilian Amazon, Indonesia is beginning to undertake critical reforms necessary to curb destruction of its carbon-dense rainforests and peatlands, says a top Norwegian official.

Speaking with mongabay.com in Jakarta on Monday, Stig Traavik, Norway’s ambassador to Indonesia, drew parallels between recent developments in Indonesia and initiatives launched in Brazil a decade ago, when deforestation was nearly five times higher than it is today.

“Fundamentally, I’m still optimistic. If you look at the trajectory in Indonesian and compare it with Brazil of ten years ago, there are similarities,” Ambassador Traavik said. “Ten years ago, things looked pretty hopeless with deforestation impacting many places in the Amazon. But now Brazil has moved to a state where there is more solid enforcement, stronger land management rules, improved monitoring, and better engagement between a range of stakeholders. Indonesia has embarked on some of the same measures.”

Those measures include a push to reform the bureaucracy that governs land use across the archipelago, improved forest monitoring systems, and stepped-up environmental law enforcement, including recent prosecutions of companies found to be illegally clearing protected forests and setting fires that drive polluting haze.

Norway has played a role in these efforts, committing up to a billion dollars in aid money to Indonesia for success in reducing deforestation. That commitment led to a 2011 moratorium on new forestry concessions across more than 14 million hectares of previously unprotected peatlands and forests. While the moratorium wasn’t as strong as originally expected—it didn’t apply to existing concessions and included loopholes for mining and energy crops—Traavik said it has nonetheless been an important development.

“People criticized the moratorium for not being effective. We wish it was more effective, but it’s not the case that it has had no impact,” he told mongabay.com. “The moratorium is still important. I am quite confident that the incoming government will look at this and maybe even strengthen the moratorium.”

Norway has also supported initiatives to boost forest monitoring, strengthen civil society, and encourage business to move toward greener practices.

Traavik said there are signs of progress on several fronts. For example, Indonesia has gotten “more serious” about stopping haze-causing fires.

“The debate has changed. Nobody questions that it’s in Indonesia’s interest to stop these fires,” he said.

“East Kalimantan has made great progress in almost eliminating fire as a structural problem. It enforces a simple rule: whenever there is a fire, it takes action. The government mobilizes law enforcement, fire fighters, and inspectors.”

And there is movement in the private sector, which is critical to building political will to shift business-as-usual approaches to land management. The ambassador pointed to recent zero deforestation commitments from Indonesian companies and last week’s unprecedented call by several prominent plantation firms for the Indonesian government to create and enforce polices that protect forests.

“The importance of what happened in New York last week has been gravely under-appreciated,” Traavik said. “It is a paradigm shift. We now have companies in the south driving the process, making definitions about what constitutes a forest and how we can protect it. This is extremely important. Already many of the key companies are on board. I’m certain this will drive the debate and give Indonesia an advantage.

“Indonesians should be proud that it is Indonesian companies such as APP and GAR driving this transformation. Kadin (Indonesia’s Chamber of Commerce and Industry) is also playing a leading role, as well as Singapore-based Wilmar.”

The change is such that some companies are talking about going beyond stopping deforestation: promoting conservation and ecosystem restoration.

“We have now gotten to a point where the private sector and the government are talking about how they can work together to protect forests across large landscapes,” Traavik said. “And what’s interesting is most of these companies are not asking for money or tax breaks. They’re asking for cooperation. This is a new situation for everyone: ministries, the government, business, civil society.”

But challenges still remain, especially when it comes to recognition of land tenure and issues of conflict.

“There’s still some confusion,” Traavik said. “Some people think there’s still a conflict between indigenous people and protected areas. There shouldn’t be. These things should be mutually reinforcing. A conservation area should very well be able to accommodate traditional peoples and traditional ways of life.”

Last year, Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono said the government would work to register traditional users’ land claims after the Constitutional Court ruled that the state had no right to seize those lands for forestry concessions. But progress has been slow to date.

In some areas, conflicting claims have caused a state of paralysis. Distinguishing between legitimate and illegitimate land claims can be a complex task, but one that incoming president Joko Widodo—popularly known as Jokowi—should be well-placed to address, according to Traavik.

“There are still a lot of conflicts that need to be resolved. This is a big job for the incoming government, but both it and Jokowi are well placed on that issue. Jokowi has good experience in solving those kinds of issues.”

More broadly, the ambassador was hopeful that the new president would continue reforms set in motion by President Yudhoyono.

“I am quite confident that the incoming government will look at [these reforms] and maybe even strengthen the moratorium,” he said, adding that the president elect is very aware of the effort to harmonize disparate land use maps across all agencies, a process termed “One Map.”

But while these details are important for driving change in Indonesia’s forestry sector, Traavik said most Norwegians are primarily interested in “whether forest is left standing or not.”

Ultimately, the best way to go about doing that will be determined by Indonesia.

“Indonesians will always know better than foreigners in fixing things,” the ambassador said. “No matter how many experts a foreigner has, it still won’t match Indonesia in terms of addressing its own issues.”

This article was written and published by Rhett A Butler, the head administrator for news.mongabay.com. For the original story and more information, please click HERE.

Despite Deforestation, Indonesia is Making Progress

Despite having a deforestation rate that now outpaces that of the Brazilian Amazon, Indonesia is beginning to undertake critical reforms necessary to curb destruction of its carbon-dense rainforests and peatlands, says a top Norwegian official.

Indonesia's deforestation rate now tops that of the Brazilian Amazon, according to a study published earlier this year. Background photo: rainforest in Sumatra.

|Updated: