The German reporter at the center of a fake news scandal might soon be charged with embezzlement.

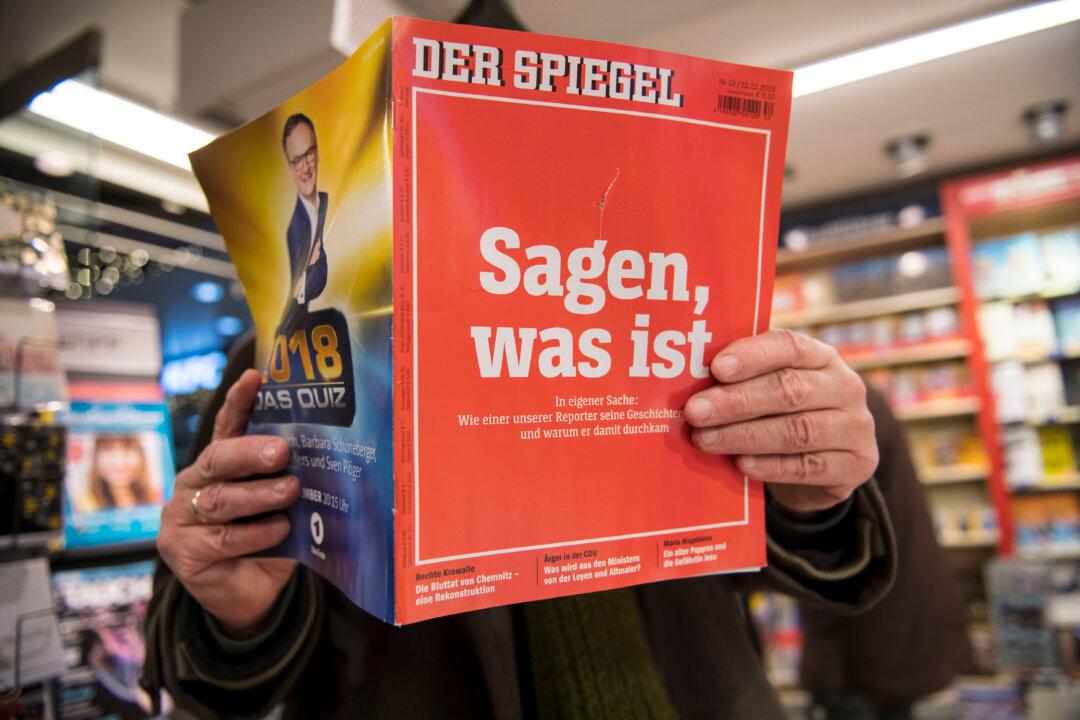

Claas Relotius, 33, was discovered to have faked some of his stories for the German weekly magazine Der Spiegel.

The German reporter at the center of a fake news scandal might soon be charged with embezzlement.