Thousands of Native Americans from hundreds of tribes gathered on the Standing Rock Sioux reservation in North Dakota, in a show of unity unseen since the heyday of Native American activism in early 1970s. Their fight, described by supporters as symbolic and momentous, aims to drive away the “black snake”—the Dakota Access Pipeline—from land the tribe claims as its own.

Meanwhile, pipeline supporters have described the 8-month protest as overblown and politicized, and said the protesters are clinging to claims unsupported by the law and using historical injustices to hinder common-sense practicalities of today.

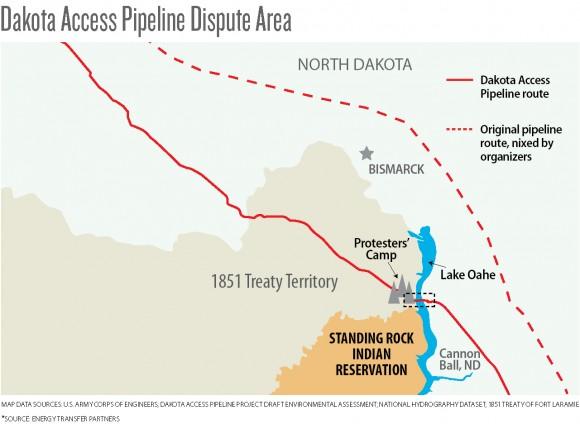

The 1,172-mile pipeline spans four states and, at one point, comes within half a mile of the reservation, where it’s slated to tunnel under Lake Oahe, a dammed part of the Missouri River and a sacred site to the tribe.

At least once, the protests have led to a violent clash with construction site security, in which both the protesters and security personnel were injured. Since then, on multiple occasions, local law enforcement has pushed the protesters away, sometimes using tear gas, pepper spray, and water cannons—a much-maligned tool in the North Dakota chill.