LONDON—Exhibitions of plastinated human cadavers have been dogged for years by claims that the bodies could be prisoners of conscience from China. Unconvinced by denials from the touring exhibitions, critics have periodically floated the idea of DNA testing, but so far, the science has remained theoretical.

Now, however, a doctor in the UK is pushing for the first extraction of DNA from plastinated tissues—to pioneer the science for investigating future exhibitions.

Consultant neurologist Dr. David Nicholl is one of several prominent medical figures and human-rights campaigners calling for an investigation into the Real Bodies exhibition at the National Exhibition Centre (NEC) in Birmingham because of concerns about the source of the bodies.

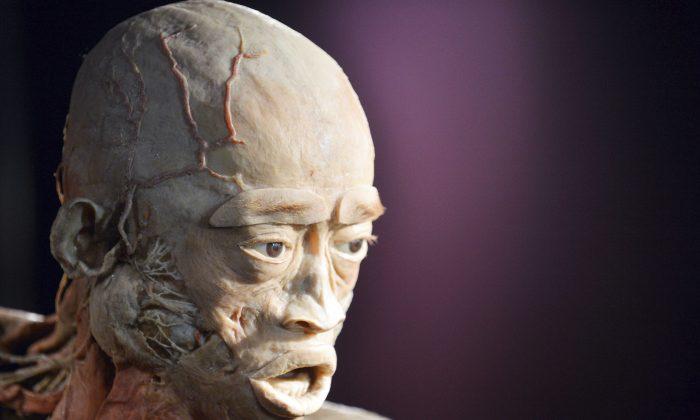

That exhibition features 20 cadavers and more than 200 organs—sourced from China—that have been preserved in a life-like state by replacing bodily fluids with synthetic materials that harden, and is billed as an “educational experience with multi-layered narratives” by organizers Imagine Exhibitions.

“It seems a completely bonkers world that we can trace a steak [to a single cow], but we can’t trace a corpse in the NEC,” he told reporters.

“I think it will provide closure to many Chinese people with missing relatives.”

Banned in Some Countries

In an open letter sent to the British government, more than 30 medical professionals, lawmakers, and activists called for the Real Bodies exhibition in Birmingham to be closed and investigated, alleging that the bodies have no documentation to confirm their origin.The company behind the exhibition, along with the NEC, denied any wrongdoing, and rejected the allegations.

Other rival exhibitions have also been touring the world.

Plastinated body exhibitions have been banned in Israel, France, Hawaii, and some cities in the United States. The Czech Republic changed its laws on July 7, 2017, to require proof of consent from the deceased before such exhibitions are allowed to enter the country.

Nicholl emphasized that the Real Bodies exhibition didn’t break any UK laws, but took advantage of a loophole in legislation on imported tissue.

The Real Bodies exhibition in Sydney, Australia. Melanie Sun/The Epoch Times

While DNA testing is straightforward and low-cost, Nicholl said that extraction of the DNA from plastinated tissue is the tricky part that needs to be established.

Looking for Bones or Teeth

Nicholl believes it would be a first. “I’ve been in contact with the editor of the Journal of Plastination, and they said that as far as they know it hasn’t been done.”Nicholl said it could be a Master’s research project and might take a year or two.

With the exhibitions unlikely to hand over samples for testing, Nicholl is hoping a teaching hospital in the UK, where plastinated specimens are used, will offer a sample of bone or teeth.

DNA Testing of 17 Million Uyghur Muslims

China expert and investigative journalist Ethan Gutmann believes DNA sampling could “explode open” the issue of organ harvesting from prisoners of conscience—a subject that Gutmann has campaigned on for over a decade.“China is right now pursuing a policy of trying to test the DNA of living Chinese people,” Gutmann said. “They’ve already tested 17 million Uyghur Muslims and they can narrow it down to within third-degree relatives, so it’s becoming possible to get a match.”

Gutmann has spent the last 10 years researching organ harvesting from prisoners in China—predominantly from Falun Gong practitioners.

Falun Gong is a spiritual discipline that draws on the Chinese tradition of slow-moving meditation exercises, combined with an emphasis on development of moral character.

According to Gutmann’s research, the epicenter of the persecution of Falun Gong was Liaoning province, and, notably, the city of Dalian.

The NEC in Birmingham said that the specimens were all “unclaimed bodies” donated by the “relevant authorities to medical universities in China.”

The NEC said the specimens were “donated legally, were never prisoners of any kind, showed no signs of trauma or injury, were free of infectious disease, and died of natural causes.”