When corals mass spawn at night on the Great Barrier Reef, the rough waves that often accompany this event could help maximize their breeding success, according to new Australian research published in Science on March 1.

After fertilization, the eggs begin to divide, forming larvae overnight that may be dispersed by ocean currents prior to settling. However, unlike most other marine invertebrates, the embryos are not shielded by a membrane, making them vulnerable to fragmentation.

“As the early-stage embryo develops, it divides into a cluster of cells,” said study co-author Andrew Heyward at the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) in a press release. “Because this ball of cells lacks a protective outer-layer, we wondered whether subjecting them to a little turbulence might cause them [to] break up.”

The researchers recreated the effects of the smallest waves on the reef by pouring embryos into another vessel containing seawater from about a foot (30 cm) above.

“This effectively mimics the kind of wave height generated by moderate wind speeds where small breaking waves, commonly called whitecaps, occur,” explained study co-author Andrew Negri at AIMS in the release.

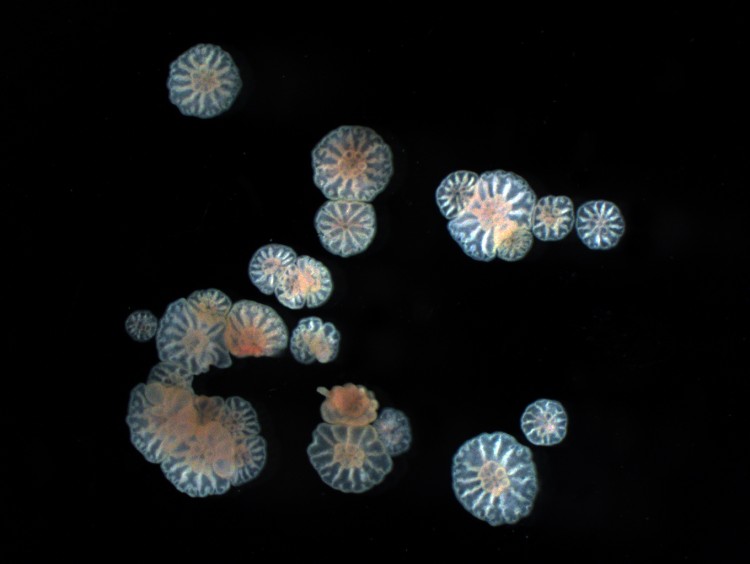

The team was surprised to observe that the fragmented embryos developed as normal, only proportionately smaller.

“Interestingly, these fragmented embryos became smaller versions of baby corals than the complete embryos,” Heyward said.

Lacking a membrane therefore appears to be a significant reproductive strategy in reef-building corals.

“Almost half of all these naked embryos fragmented in our experiments, suggesting that this has long been part of the corals’ repertoire for maximizing the impact of their reproductive efforts,” Negri said.

Corals can also propagate asexually by cloning. However, using this mixed breeding strategy, genetically different offspring are produced via sexual reproduction, followed by planktonic cloning.

The researchers plan to investigate this phenomenon further, and understand how corals benefit by producing such fragile embryos.

“It is surprising how fragile the embryos are during early cleavage,” Negri told The Epoch Times via email. “Our most recent experiments show that coral larvae can develop from the fragmentation of 64- and 128-cell embryos (which have the shape of raspberries).”

“Fragments from those embryos were often made up of more than one cell and the tiny larval clones we saw may have developed from multiple cells.”

As corals can produce more than 100,000 eggs from a single colony, potential advantages of fragmentation include an increased number of viable embryos and chances of colonizing more beneficial habitats.

“It may also be an advantage to produce a range of size in larvae and early polyps to avoid certain predators,” Negri said. “Also size may affect the developmental rate of larvae which could influence their distribution and recruitment.”