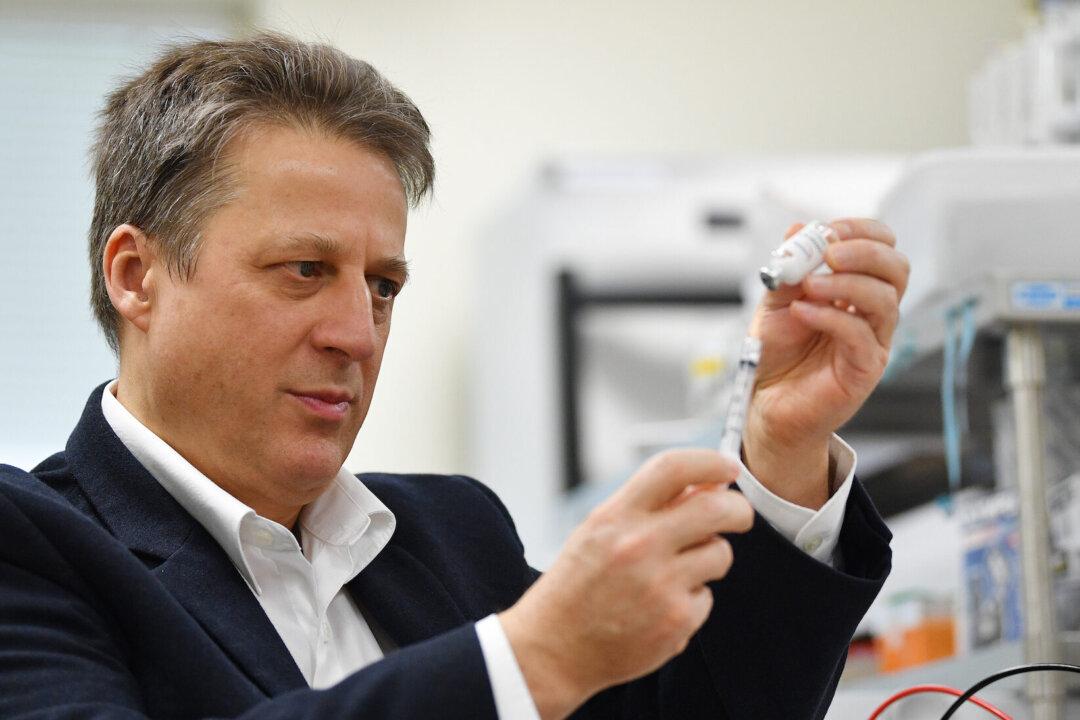

Billions of dollars in government funding ploughed into COVID-19 vaccine research during the pandemic has helped push the boundaries of drug research beyond their usual limits in the race to create the jab, says lead researcher of the Spikogen (or COVAX-19) vaccine.

Professor Nikolai Petrovsky says the pandemic has been a springboard for major drug firms to further secure their dominance in the pharmaceuticals industry after aggressively securing massive government contracts.