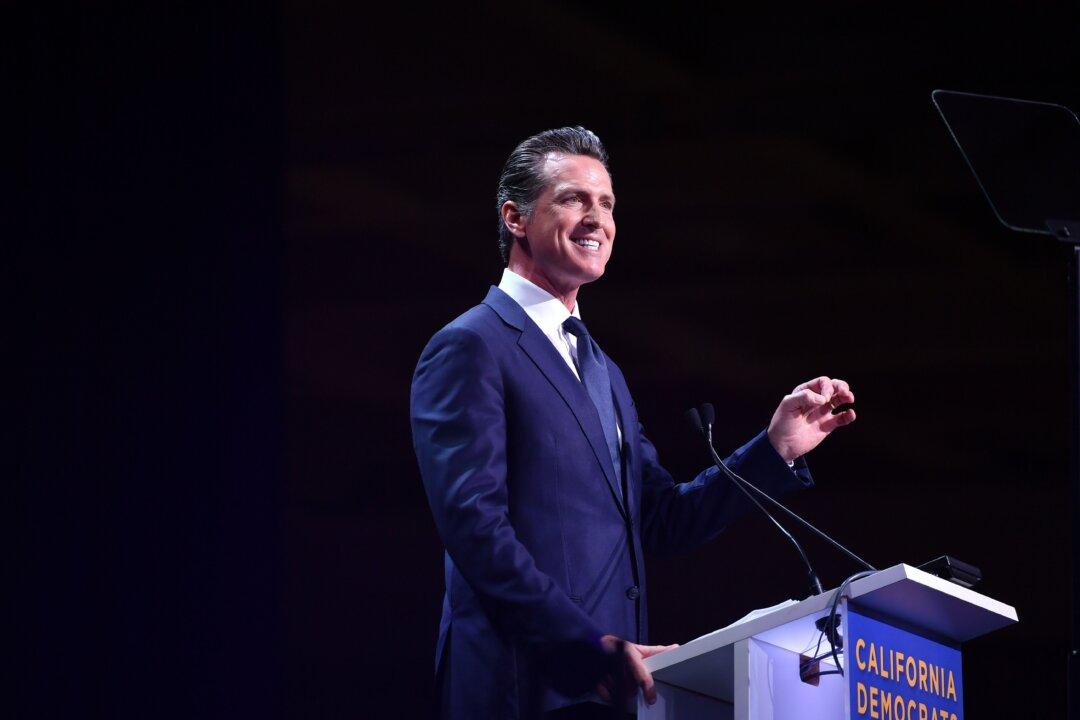

If California Gov. Gavin Newsom has it his way, a state prison will be closed sometime before he kicks the bucket.

“I would like to see, in my lifetime and hopefully my tenure, that we shut down a state prison. But you can’t do that flippantly. And you can’t do that without the support of the unions, support of these communities, the staff, and that requires an alternative that can meet everyone’s needs and desires,” Newsom told the Fresno Bee editorial board recently.